THE CHOICE: FREE WILL OR A MULTIVERSE

In this essay I shall present an argument that, since we live in a universe that conforms to Einsteinian cosmology, we must either deny the existence of the multiverse or deny the existence of free will.

Reasons for believing in the multiverse.

Before looking into why Einsteinian cosmology forces this choice upon us, let’s look at the reasons given for supposing there is a multiverse. There’s actually very little evidence to prove there is a multitude of universes. It’s not like we can observe them as we can other galaxies or stars. Instead, the hypothesis has been put forward as a way of explaining problems in modern cosmology.

One such problem has its origins in Big Bang theory and is known as the ‘horizon problem’. Throughout space we detect a uniform temperature of about 2.7 degrees above absolute zero, and this is believed to be heat left over from the Big Bang itself. When I say ‘uniform’, I mean really uniform. Wherever we point our instruments, they read a temperature that is never more than a thousandth of a degree different to the temperature of other regions of space.

This is problematic for the Big Bang, because in order for there to be such a uniform temperature, sufficient time must pass for one region of space to influence the other. In older Big Bang cosmologies, this could not have happened, and the reason why not has to do with the ‘horizon’ referred to in the ‘horizon problem’. This horizon marks the boundary beyond which one region of space no longer has sufficient time to influence another. Such a boundary existed in older Big Bang models, making the uniform temperature of space a real mystery.

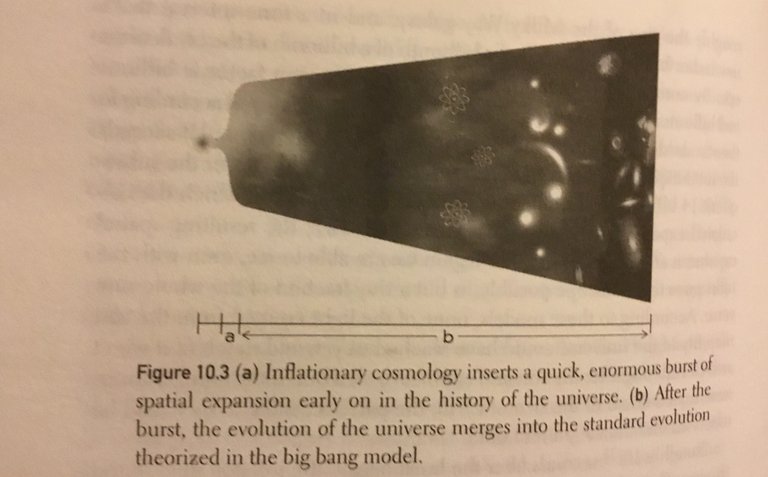

Inflationary cosmology

(Image from ‘The Fabric Of The Cosmos’)

‘Inflationary Cosmology’ was dreamt up in order to resolve this problem. According to inflationary cosmology, the universe experienced a brief period of rapid expansion. Actually, that’s putting it mildly to say the least because, according to its originator Alan Guth, the period of inflationary expansion was equivalent to something the size of a DNA molecule expanding to something the size of a galaxy, and all in a period of time far shorter than a billionth of an eye blink. By supposing that the universe underwent this brief period of rapid expansion, we can wind the clock back less than half way and so bring any two regions of space within the boundary of influence.

In order for there to be the necessary period of brief expansion, there had to be something that could cause it. Guth proposed an ‘inflaton field’, which is kind of like an anti-gravitational force. It so happens that Einstein had also included an anti-gravity force in his theory of General Relativity. He called it the ‘cosmological constant’. But in that case, it was included so that its effect would balance out the attractive force of gravity and lead to a static universe. When it was later proved that the universe is expanding, Einstein called the cosmological constant his greatest blunder. In Alan Guth’s inflationary model, the inflaton field has a repulsive force that is 1000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 times stronger than Einstein’s cosmological constant.

Now, in order for inflationary theory to match observations, the period of rapid expansion must come to an end. Once that happens, the energy from that force has to go somewhere (because energy can only be transformed, not created or destroyed) and it gets converted to heat and thereafter the universe evolves according to more traditional Big Bang cosmologies. The problem was, nobody could show that the inflaton field would lose all its power. Instead in some regions decay would occur while in others its repulsive influence would still be expanding the fabric of spacetime. This lead other cosmologists like Andre Linde to suppose that, actually, the inflaton field never completely runs out of power. Since the inflaton field puts the ‘bang’ into the ‘Big Bang’, ‘eternal inflation’ (as Linde’s model is called) means the Big Bang was not a unique event but one that has happened infinite times in the past and will continue to happen in the infinite future. Universes are constantly popping into existence as regions of the infinite inflaton field go through their brief period of rapid expansion followed by a gradual increase of entropy.

Many laws of physics

Another reason for supposing that the multiverse exists has to do with such things as the mass of the various fundamental particles that are thought to make up everything we see around us, and the forces that govern their behaviour. In order to get our universe the strength of gravity and other values has to be very precisely tuned because otherwise you get a universe that is hostile to our form of life. The problem is, there is as yet no convincing reason why the numbers have to conform to those precise values. Some physicists get around this problem by suggesting many universes, each with different laws of physics. For obvious reasons, we find ourselves in one which just happens to be able to support us.

As I said before, nobody has ever observed another universe. It’s just that our own universe seems far more improbable if we deny the existence of the multiverse, and it does fill in quite a few gaps in our Big Bang models if we suppose the multiverse exists. But quite a few people don’t like the concept. It smacks of explaining away problems rather than resolving them. And, also, the very idea of there being infinite universes seems to some to make everything too complex. You might as well invoke the intervention of an infinitely powerful god to explain why everything is how it is. Those might strike you as fair points, but I don’t think people who hold this view understand that if there is no multiverse, then free will cannot truly exist.

Why there is no free will in an Einsteinian universe.

OK, so why do I think that? Well, it all has to do with the nature of space and time in Einsteinian cosmology. In such models, space and time are unified into a four-dimensional entity known as ‘spacetime’. In everyday language, we give instructions to navigate our way through two-dimensional space. We tell others to ‘travel north-west’ in order to meet up at a specific location. We also give instructions that can include a third dimension (“and then go up to the fourth floor”). Finally, our instructions for navigating space can include the fourth dimension (“travel northwest, go up to the fourth floor, and make sure you are there by 3:30”).

However, in everyday thought we treat the fourth dimension of time differently to the other three spatial dimensions. How? Well, when it comes to the spatial dimensions we believe that other regions exist at the same time as the one we happen to find ourselves in. In other words, if you happen to be in London right now, you don’t think that New York has no existence until you arrive there. No, it exists simultaneously with all other locations in three-dimensional space.

But that is how we regard the temporal destination we call ‘the future’. The future has yet to occur; it has not happened yet. It comes into being when we ‘travel’ there and the future becomes our present while what was the present is now the unalterable past. And that is another way in which the future is thought to be different. The past is what it is, we cannot change it. But the future is open, “there is no fate but what we make” as Terminator 2 put it.

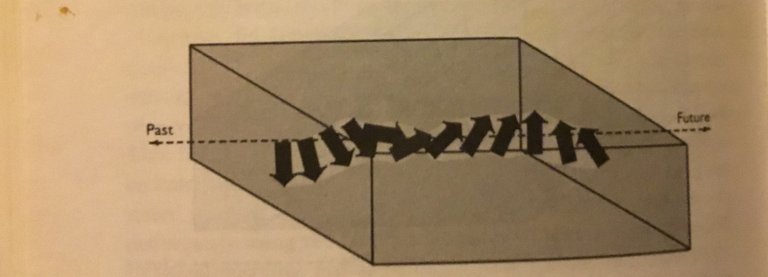

But think back to how space and time is represented in Einsteinian cosmology. These are dimensions unified into one four-dimensional entity. As well as being referred to as ‘spacetime’, it is also sometimes called the ‘block universe’ because, according to David Deutsch, “the whole of physical reality-past, present, and future-is laid out once and for all, frozen in a single four-dimensional block...What we call ‘moments’ are certain slices through spacetime”.

(A representation of the block universe. Image from ‘The Fabric Of Reality’)

The key observation is that, from this Godlike perspective outside of the universe, all of spacetime exists as one block. The future is there, just as fixed as the past. But, if the future already exists, if it is just another slice in the block of spacetime that is our universe, then each and every event we experience is akin to a destination that pre-existed. In other words, the future is no more open than the past. Cause and effect really have nothing to do with one another because nothing can turn out any other way. Instead, all we have is the illusion of free will (oh, and the illusion of time passing and motion occurring, which are other things that don’t exist if you view Einsteinian universes outside of the ‘block’).

If the future is as fixed and unalterable as the past (and it is according to Einstein’s model), this seriously undermines free will. After all, choice plays a huge part in our understanding of free will. We tend to be more lenient toward people who do bad things they could not have avoided doing, considering their very powerlessness to change the course of events justification for absolving them of blame. But if we live in a block universe, where all events exist as slices in a single four-dimensional entity, then there can be no choice regarding how things turn out. In a way, I wrote this article not because it was my choice but because my future self already wrote it and all I am doing is heading toward the one and only future available in the block. The future is what it is, and it cannot be different.

But this deterministic outlook changes if there is a multiverse. To say the future can turn out differently is to say that there are many different futures. This is really no different to believing in alternative (or many) realities. Saying “I could have chosen otherwise” is to believe in alternative universes where copies of yourself did choose otherwise. If there is only one universe and it conforms to Einsteinian cosmology (with spacetime frozen into one block that exists once and for all) then we have no free will because the future cannot be changed and choice plays no role whatsoever in how things turn out. But if there is a multiverse, then there are infinite possible futures and free will is restored.

REFERENCES

“The Fabric Of Reality” by David Deustch

“The Fabric Of The Cosmos” by Brian Greene

“Just Six Numbers” by Martin Rees