sex is a peculiar thing. In spite of the fact that sex is involved, necessarily I might add, in the propagation of pretty much all life on Earth, many of us become strangely awkward when the subject comes up. In those moments, it’s as if we somehow want to act like sex doesn’t happen, or if it does, it happens to someone else, or perhaps only among other species. Human babies aren’t created through sex, we suddenly and shyly insist — they’re delivered on random days by storks, or Amazon Prime.

If you think I’m exaggerating, then allow me to introduce Exhibit A, a male shopper at Target who realizes that in pushing around his oversized shopping cart with that kind of Walking Dead gait that often afflicts shoppers in big-box stores, he has inadvertently wandered into the Intimate Apparel section. (On a side note, maybe we should have a discussion about why Intimate Apparel is inherently gendered in most places. Seriously, just ask any clerk at Target, “Excuse me, where is the men’s intimate apparel section?” and you will no doubt be greeted with, “You mean pajamas?”) If Exhibit A is like most men, he will do his best to mask his embarrassment and either reverse his tracks without calling too much attention to himself or else push on through as if he were intentionally taking a newly discovered shortcut to the automotive section.

Our personal discomfort with sex is evident in how the law interprets and judges our sex lives. My own interest in this uneasy relationship between law and sexuality started when I came across a 2017 criminal case in Alabama in which a 31-year-old woman had been charged with second-degree rape and second-degree sodomy against a 14-year-old male victim. My first line of inquiry was to ponder how different degrees of rape and sodomy were defined, which led me to look up their descriptions in the Alabama criminal code. Then I investigated how Alabama’s criminal code compares to the criminal codes of other states when it comes to sex crimes, which eventually gave way to investigating how the criminal codes of each state view sex and sexuality in general.

Human babies aren’t created through sex, we suddenly and shyly insist — they’re delivered on random days by storks, or Amazon Prime.

What I discovered was as interesting as it was unsettling. I’ll have plenty of examples to discuss in due course, but the short answer is this: What most of us would probably consider a healthy and vibrant sex life the law sees as a crime spree of unspeakable acts of sexual deviance and perversion.

Let’s Talk About Sodomy

In spite of the fact that the United States has a secular legal system, sodomy as a crime has decidedly biblical origins, specifically in the book of Genesis 18–19. The modern English term is a historical derivative of the Latin phrase peccatum Sodomiticum, or “the sin of Sodom,” which immediately raises the question of what exactly the sin was that was committed by the people of Sodom that eventually led God to destroy the entire city (along with its parallelly perverted town Gomorrah). Many people believe quite fervently that the sin of Sodom was homosexuality, or to be more precise, the male population’s engagement in homosexual sex acts, but as it turns out, this interpretation is largely incorrect, or at the very least, incomplete.

While it’s true that the men of the city came to the house of Lot (Abraham’s nephew) and demanded that he turn over his two out-of-town male guests (who were in fact angels incognito) so that they could have sex with them, when Lot offered his two virgin daughters to the men instead, they did not refuse on the grounds that they were only interested in men. Rather, they refused because they were annoyed that Lot did not comply with their initial request. The sins of Sodom were many, including the complete disavowal of the rules of hospitality, but chief among them was the fact that the insatiable desire for sex, which led to mass rape, was based on hedonistic gratification rather than procreation.

What most of us would probably consider a healthy and vibrant sex life the law sees as a crime spree of unspeakable acts of sexual deviance and perversion.

The history of the evolution of sodomy as a legal term is long and twisted, and over time it has become legally associated with anything from oral and anal sex to bestiality. The only point of consistency in its history is that all of the sexual acts that are considered sinful or deviant or illegal are sex acts that do not or cannot result in procreation. What makes them wrong is that they do not further the presumed divine mandate to beget future generations and they are undertaken purely for the purpose of hedonistic pleasure. This, coincidentally, is exactly the perspective they take in the criminal codes of so many states.

The legal word used to describe sodomy is “deviate” (rather than deviant, to which it is etymologically related). The Oregon criminal code, for example, defines deviate sexual intercourse as “sexual conduct between persons consisting of contact between the sex organs of one person and the mouth or anus of another.” You might think that’s just one more example of “keeping Oregon weird,” but in fact most states use the same definition. There is something oddly specific about this definition, though — contact between the sex organs of one person and the ears of another, for example, something that could rightfully be called aural sex, is apparently unheard of among lawmakers.

The crime that is actually defined in the various state-level criminal codes is involuntary deviate sexual intercourse — something that is quite rightly viewed as a horrible crime of sexual violence. What I find interesting is how the criminal codes of so many states retain the language of “deviate sexual intercourse” even when it isn’t a crime.

So, what exactly does deviate sexual intercourse deviate from? Well, this is where we have to return to the surprisingly biblical influence on what is supposed to be a body of secular law, because the word deviate still refers to any sex act which cannot result in procreation. Sex for procreation is normatively regarded as proper sex — anything else is a deviation, if not a full-blown perversion, in the eyes of the law.

The Stigma of Perversion

At this point you might be thinking, “Well, what’s the point, consensual deviate sex is perfectly legal, so this is really a non-issue, right?” I would argue, however, that leaving that word “deviate” in descriptions of non-procreative sex allows discriminatory beliefs to persist and creates an environment that smothers the open discussion of sexuality.

It is true that consensual deviate sex is perfectly legal, though the landmark decision that established that precedent is of surprisingly recent vintage. The legal cases that led to the affirmation that we are indeed entitled to participate in consensual deviate sex without fear of criminal punishment all focused on the issue of sodomy, insofar as laws in the criminal codes that related to sodomy in essence criminalized homosexuality by criminalizing sodomy. Bowers v. Hardwick was decided by the Supreme Court in 1986, following a criminal case from Georgia in which police encountered two men engaged in sexual relations in the bedroom of their home.

Sex for procreation is normatively regarded as proper sex — anything else is a deviation, if not a full-blown perversion, in the eyes of the law.

The Bowers decision affirmed that the two men, like all U.S. citizens, were entitled to the right to privacy, which extended to consenting adults engaged in private acts of intimacy. But interestingly, or perhaps disturbingly, the Supreme Court did not rule that Georgia’s laws criminalizing sodomy and homosexuality were inherently unconstitutional. It wasn’t until the case of Lawrence v. Texas (2003) that the Supreme Court finally ruled that the right to privacy applied to all consensual intimate relations in such a way as to invalidate all parts of any state criminal code that criminalized sodomy or homosexuality.

While Lawrence v. Texas may have invalidated laws that criminalized sodomy and homosexuality, it did not actually require states to remove those laws from their criminal codes. Many states — Alabama, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, and Virginia, to be precise — have retained the laws that describe homosexuality and sodomy, even when consensual, as “deviate” sex acts (including oral sex). Indeed, the very laws that were at the heart of Lawrence v. Texas, such as Section 21.06 of the Texas criminal code which states that “a person commits an offense if he engages in deviate sexual intercourse with another individual of the same sex,” are still on the books. Lawrence v. Texas made such laws unenforceable, but it did not require states to remove them or revise their language. States like Texas, in other words, can no longer criminally prosecute homosexuality as a “deviate” sex act, but they can still describe it as such and express their official disapproval.

Neither Gone nor Forgotten

While all eyes are currently focused on Roe v. Wade in relation to the reshaping of the Supreme Court in the time of Trump, there are other key areas where the possible backsliding of previous precedent might be of equal concern. It would be easy to think that Lawrence v. Texas finally settled the issue that all consensual sex acts, whether deviate or not, are protected by the right to privacy, but in reality this is an issue that refuses to go away. In Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), the Supreme Court case that legalized same-sex marriage, the opposing side argued that same-sex marriage should not be recognized as it severs the intrinsic link between marriage and procreation.

The court rejected that argument, finding that if the purpose of marriage were to legally protect sex acts leading to procreation then this would, among other things, invalidate marriages where a spouse were sterile or infertile (and would also make their sex “deviate”). But remember that Obergefell v. Hodges was a 5–4 decision. A different Supreme Court might see things differently, and leaving intact the legal language at the state level that deems anything other than procreative sex as “deviate” only adds rhetorical fuel to the fire.

Sex, How do I Consent to Thee?

Let me count the ways. Actually, before I count the ways, let me state up front that I take the issue of consent very seriously. No means no, in any context. I say that because I don’t want anyone thinking I am somehow making light of the situation, or trying to argue that the issue of consent is “really complicated” so it’s tough to say who did what to whom. What I am going to argue, however, is that the issue of consent is discomfitingly inconsistent when it comes to the definitions and consequences of sex crimes, as defined in the criminal codes themselves.

The issue of consent is crucial because it is the one thing that separates legal deviate sex from illegal (aka criminal) deviate sex. Remember, in the eyes of the law, it’s all still deviate sex, but only some of it is illegal. So how is consent defined, and who exactly can give valid consent? You might think the United States has adopted the international human rights standard that anyone below the age of 18 cannot legally consent to anything, but in fact we allow for individual states to set their own age-of-consent standards. As a result, the standards differ significantly from state to state. The age of consent in California is 18, for example, but it is 15 in Arkansas.

Even then, the law doesn’t see consent as an either-or issue, and there are different degrees of wrongness and criminality depending on the age of the victim. The less able a victim is to understand what consent is or to give consent at all, the greater the crime and punishment of the perpetrator. The standards for this, however, are again weirdly inconsistent.

I mentioned earlier the case of a 31-year-old woman in Alabama charged with second-degree rape and second-degree sodomy for her acts against a 14-year-old male victim. So how does the Alabama criminal code define these two criminal acts, and how is second-degree sodomy different from first-degree sodomy? First let me offer up the definitions straight from the criminal code itself, then I’ll point out a few things that should give us cause for concern.

Here is how the Alabama criminal code (Section 13A-6–62) defines second-degree rape (a Class B felony):

Being 16 years old or older, he or she engages in sexual intercourse with a member of the opposite sex less than 16 and more than 12 years old; provided, however, the actor is at least two years older than the member of the opposite sex.

He or she engages in sexual intercourse with a member of the opposite sex who is incapable of consent by reason of being mentally defective

And here is how the Alabama criminal code (Section 13A-6–61) defines first-degree rape (a Class A felony):

He or she engages in sexual intercourse with a member of the opposite sex by forcible compulsion; or

He or she engages in sexual intercourse with a member of the opposite sex who is incapable of consent by reason of being physically helpless or mentally incapacitated; or

He or she, being 16 years or older, engages in sexual intercourse with a member of the opposite sex who is less than 12 years old.

Just to be complete, here is how the Alabama criminal code (Section 13A-6–64) defines second-degree sodomy (also a Class B felony):

He, being 16 years old or older, engages in deviate sexual intercourse with another person less than 16 and more than 12 years old.

He engages in deviate sexual intercourse with a person who is incapable of consent by reason of being mentally defective.

And for comparison, here is the criminal definition is how the Alabama criminal code (Section 13A-6–63) defines first-degree sodomy (a Class A felony):

He engages in deviate sexual intercourse with another person by forcible compulsion; or

He engages in deviate sexual intercourse with a person who is incapable of consent by reason of being physically helpless or mentally incapacitated; or

He, being 16 years old or older, engages in deviate sexual intercourse with a person who is less than 12 years old.

There are a ton of things going on here, so let me pull out a few for closer investigation.

The crime of rape, in both the first and the second degree, requires the act to be perpetrated against a member of the opposite sex. This would mean that all rape is heterosexual by legal definition, and it is thus referred to as “sexual intercourse.”

The definition of sodomy (in both the first and the second degree) no longer requires that the act be committed against a member of the opposite sex, meaning that homosexual acts may be involved, and so note how the description has now shifted to “deviate sexual intercourse.” A rape that occurred involving members of the same sex would not be treated as rape, but rather as sodomy. The criminal definition also implies that all homosexual acts are in some way “deviate.”

Alabama, like the vast majority of criminal codes, still uses the phrase “mentally defective.” You’d think that with all the efforts made in recent decades by disability rights activists, we could convince states to make a simple word change so that it reads “mentally disabled” or “cognitively disabled” or something else that offers equal dignity to all. But no, Alabama, like many other states, still uses the very outmoded and inappropriate term “defective.”

There is a difference between the victim being “mentally defective” and “mentally incapacitated.” What this means in plain English is that the act of rape or sodomy against a person with a mental disability is less of a crime than the same act against a person who is mentally incapacitated (for instance, drugged). When we get to this level of heinousness, do we really need to establish standards for subtleties?

The key issue in all of this is consent, and the degree of consent is determined by somewhat arbitrary standards. As can be gleaned from the wording of the laws, the age of consent in Alabama is 16. For those under the age of 16, the degree of criminality is determined by the age of the victim: either 1) younger than 16 and older than 12, or 2) younger than 12 years of age. Close readers of the law will notice a strange error in the wording of these crimes, namely that none of them covers a person who is exactly 12 years of age.

Romeo and Juliet to the Rescue?

When I said the standards were somewhat arbitrary, I meant that they are inconsistent across the state criminal codes and also based on age differentials that are not explained in any meaningful way. Even in states that use the same age differentials, a sex crime that is a Class B felony in one state (such as Alabama) becomes a Class C felony (lesser offense) in another (such as Kentucky). None of this makes much sense.

Even in progressive California, where we have tried to eliminate the phrase “deviate sexual intercourse” from the criminal code, we still have an odd moral calculus at work in how we differentiate the seriousness of sex crimes. California criminal code section 286, for instance, which defines sodomy against a minor (the age of consent in California is 18), differentiates criminality by two age groups: 1) victim under 16 (felony, up to three years in prison), and 2) victim under 14 (felony, up to eight years in prison). Yet in the separate category of “sodomy by force or fear,” the age differentials become: 1) victim under 14 (felony, up to 13 years in prison), and 2) victim over 13 (felony, up to 11 years in prison).

Despite its progressive reputation, California does not have a full “Romeo and Juliet” law in its legal arsenal, as many other states do. California has only a partial one. Romeo and Juliet laws are designed to address the situation when two people in a consenting sexual relationship are similar in age but one has crossed that magic dividing line of 18 years of age, which muddles the issue of legal consent. California’s version, which states that both people must be above the age of 14 and less than three years apart in age, is considered partial because it only downgrades the act of sexual relations from a felony to a misdemeanor, and the downgrade is not automatic but at the discretion of the court. In Hawaii, by contrast, the age of consent is 16, and the legally permissible age difference according to the Romeo and Juliet law of Hawaii is five years.

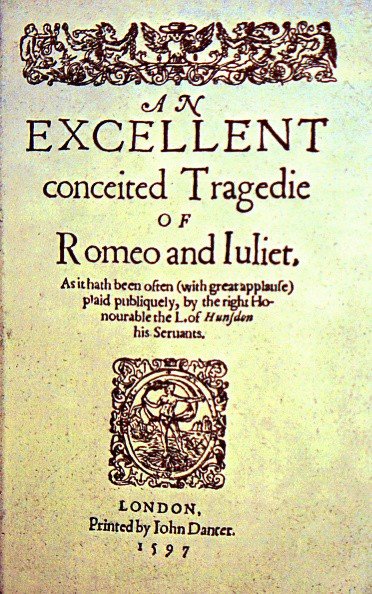

Also, can’t we think of a better name for these laws than “Romeo and Juliet”? Sure, the two names are synonymous with youthful, passionate love, but in the end — sorry, spoiler alert — they both die in tragic circumstances.

Perversity, Criminality, and Clarity

So, where does this leave us in terms of sexuality and the law?

First, I think it’s time we get rid of the language in our criminal codes that differentiates sex acts by whether or not they can result in procreation. Not only does it maintain a link to scriptural interpretations of sexuality that undermine what is necessarily a secular legal system, but it also allows negative opinions of non-normative sexuality to persist and in some cases, even encourages discriminatory views toward homosexuality insofar as some states still officially describe homosexuality as “deviate.”

Second, privacy is a fundamental constitutional right as well as a human right, and at least in the United States, it is a right that protects all intimate acts between consenting partners. Whether or not those intimate acts relate to procreation is a meaningless question, and has no place in the language of the law.

Third, considering that the one thing that legally divides an intimate sex act from a criminal one is the issue of consent, we really need to have a conversation about what consent is and who has the legal authority to give it. Our laws are all over the map on this question, and it seems unacceptably odd that a relationship that would be legal in one state would be a felony in another. On top of that, we have this question, which many a young person has rightfully pondered: How is it that on my 18th birthday, I am perfectly capable of consenting to sex that might lead to procreation and bringing a new life into the world with all the responsibilities that entails, yet in the eyes of the law I still have to wait three more years before I can be trusted with a glass of wine?

On that note, I’ll bring this discussion to a close, and wish all of you a very deviate day, whatever that means.