About a month ago, @coinbitgold posted a cool article about her love-hate relationship with a PhD.

https://steemit.com/phd/@coinbitgold/love-hate-relationship-with-phd

I wanted to continue the discussion by talking about a slightly different perspective as a graduate student in neuroscience.

PhD vs. MD

It is often a difficult decision for students in the sciences to choose between going into a medical or health professional field or into scientific research. This isn’t the case for everyone, but a lot of people, including me, like aspects of both career paths. You can get both degrees, but that takes at least 7 more years after an undergraduate education if you don’t take time off, plus at least one residency, and often one academic post-doc if you really end up doing both.

I went to a small, liberal arts college, which has many pros but also cons. One of those cons is that I had minimal exposure to big research projects. Because I didn’t have experience with research, I was leaning towards the medical school route, and had even started my applications when I had the opportunity to attend a 3-month summer research internship at Baylor College of Medicine. I worked with an awesome mentor, Dr. Joseph Hyser, and the whole experience made it really clear that a PhD was the way to go.

I loved that sort of by definition in research you will always be pushing the boundaries of human knowledge. There is some monotony in the day-to-day, but it’s an exhilarating feeling that you are contributing to human progress, even in a small way. I loved the environment of being surrounded by nerds who, for the most part, are type B personalities who like to have fun and find a huge variety of topics fascinating. I loved the creativity and problem solving involved and the sense that doing research would really sharpen my mind.

I’ll be honest and say that a large part of it was also financial. I know that most people think of it the other way around, because PhDs often make pennies out of grad school in academic post-docs or adjunct faculty positions, and medical doctors make a lot. But from my perspective, it seemed like an awesome deal. I wouldn’t have to go into debt, which to me translates to freedom (if I ever change my mind, I can pick up and go do anything). Also, I’m getting paid to go to school. How cool is that? Especially for us nerds that LOVE going to school. Within a few weeks of starting my research internship, I ditched the expensive process of applying to med schools and started on my applications for PhD programs.

Harsh realities – from my perspective

I think that the difficulty in getting an academic position with a PhD is worse in the humanities than it is in the sciences. I was talking to a friend recently who is doing a PhD in English, and she said that during a workshop for ‘altac’ (alternatives to academia) careers for PhDs in the humanities, they were suggesting to learn skills like programming. I guess the idea is that since many of these students had to learn a few languages as part of their education, those skills might translate to learning computer languages. The point is, it’s a dire state of affairs when the advice someone gives you about what to do with your skillset is “find a new skillset.”

Even in the sciences, there are few academic positions relative to how many PhDs there are. There are some other problems, too. First, a lot of professors, who advise and mentor us, entered academia at a very different time, where finding a good tenure-track position was easier and competition for grant money was not as fierce. Naturally, that are preparing us to follow in their footsteps, even though only a small percentage of us will be able to successfully.

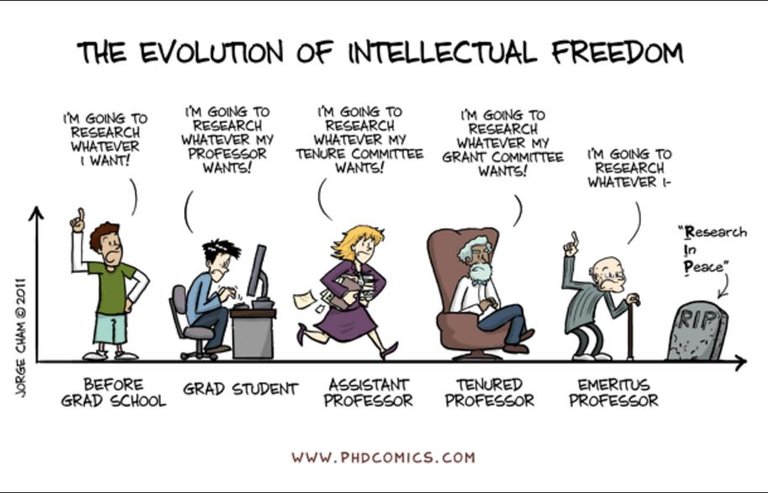

Secondly, one of the narratives of academia is that you have lots of freedom as a director of your own lab to research whatever you want to, but I don’t think that this is very true anymore. This freedom is supposed to be one of the big perks of working in academia. However, because of how competitive grant funding is, many professors are setting aside their true research passions to pursue work in areas that are more heavily funded. At the same time, it seems like opportunities to do research outside of academia are expanding.

For myself, I think that my future path depends on the opportunities that knock on my door, and my best strategy is to keep an open mind. I think that the PhD still has its place. Doing my PhD has had the feel of a medieval apprenticeship, where I am training directly under master scientists for a long period of time. I think that the reason that PhDs are still set up this way is because much of the process is learning how to think in the same way as other master scientists. This is beyond just taking the time to learn useful skills and the knowledge of your field. That being said, those skills and knowledge also take a long time to acquire. Honestly, I think it takes even longer than the PhD, but we can at least set off on our own with some solid footing.

You can do a lot with a PhD outside of academia. Theres nothing wrong with being a research "whore" and doing it for the $$$. I do.

First of all, I LOVE that cartoon!

I'm currently pursuing my Ph.D. in Somatic Depth Psychology (a non-clinical program, focused mostly on qualitative research), and I know that I have very slim chances at a traditional academic career. And I'm OK with that. I'm excited to keep having these conversations with grad students and Ph.D's across the spectrum about the kind of shifts we all would like to see in the community. And I'm also excited to see the various different paths and opportunities we create for ourselves!