In the early 90s, living in Kenya, I was working for an aggressive African merchant bank. You may recall the rather infamous “landing” of the US Marines on the shores of Somalia in 1993. Well, I thought there might be some opportunities for business given the fact that literally millions of USDollars were being poured into the country on a monthly basis by the UN and other donors—there must be something we could do to help manage the flows at a minimum! Notwithstanding the human tragedy of it all (and believe me, it was a tragedy of gargantuan proportions), it was actually a very exciting and adrenalin pumping time.

At its peak, the UN was flying into Mogadishu from Nairobi an average of twice a day. All one had to do was call the UN office; ask if there was space available; and, if so, you were on the flight! I would work Monday through Friday in Nairobi; fly to Mogadishu on Friday or Saturday; and return on Sunday or Monday.

I did this for about nine months and some of the stories I could tell. For example, it is the only time in my life that I have ever flown free—I didn’t even have to use my precious frequent flyer miles! And, it is the only time I have actually been able to “hitch-hike” rides on airplanes! Here’s the way it worked. After getting on a UN flight to Mogadishu, you then had to be concerned about getting to other parts of the country, or back to Nairobi. There were two options; wait for a UN-scheduled flight to your preferred destination, or (and this was the fun part) check around the airfield for other departures. You see, many Western nations had contributed to the cause and had “donated” the time and equipment of their respective Air Forces to the peace-keeping (or “peace-making”) effort. Each one of them had its own position around the airfield, and all you had to do was walk around and ask where they were going and when. If they had space, you were generally welcome aboard!

I will never forget one time when some of our executives came to visit in Nairobi and I insisted that they accompany me to Mogadishu. I was trying to get us involved in a telecoms deal—after all, the telecommunications system in the country was an absolute disaster—and wanted to demonstrate to the UN and other players that we were serious. Needless to say, our executives, while supporting me from long distance (they were based in New York), had absolutely no desire to go to Mogadishu—it was a country going through a civil war; what, was I crazy! Here’s the irony of it all, these executives were African themselves—but living in New York!

At any rate, I managed to convince them that they had to go; so we did, UN flight and all. By that time, I had become good buddies with the Administrative Officer (I think that was his title) from the UN in Mogadishu—the senior UN civil service official in the country—and he sent his car to the Mogadishu airport to pick us up. All of a sudden, my “stature” jumped up in the eyes of my superiors. Our meetings went well and we returned to the airport with these guys still glowing from the reception and ready to do any deal I would propose. Unfortunately, things turned a bit sour at this point. There was no other UN flight back to Nairobi that day and these guys had to catch a flight that night. My fortunes were rapidly turning and I had to do something. So, I did the only reasonable thing. I told them to stay put and ran around the airfield trying to find out if any of the Air Forces present would be going back to Nairobi that day. Luck was with me. I’m not sure, but I believe it was the Aussies; they were flying to Baidoa to drop some cargo and then on to Nairobi, and, of course, we were welcome to come along. There was only one problem. It was a cargo flight; there were only four seats (outside of the cockpit) attached to the floor of the fuselage and they were reserved for some VIPs to be picked up in Baidoa. We would have to sit on the floor of the fuselage and be strapped to the interior walls of the plane. Hey, we had to get back to Nairobi, right. I ran back to the terminal; gathered my rather vexed executives and returned to the Aussies. The aircraft was one where the back end drops down and you walk up and in. We did so and these executives were quite pleased to see the four seats that had been arranged; not so pleased when they found out that the seats were for others—but they could sit in them until we got to Baidoa, which they did. At Baidoa, they had to strap themselves to the interior wall, sitting on the floor (if that’s what you call it) for the remainder of the flight. Presidents and Executive Vice-Presidents don’t take kindly to such treatment; especially if they are African! We made it back to Nairobi; they caught their flight; but, not surprisingly, we never did the telecoms deal and they never returned to Mogadushu. Go figure!

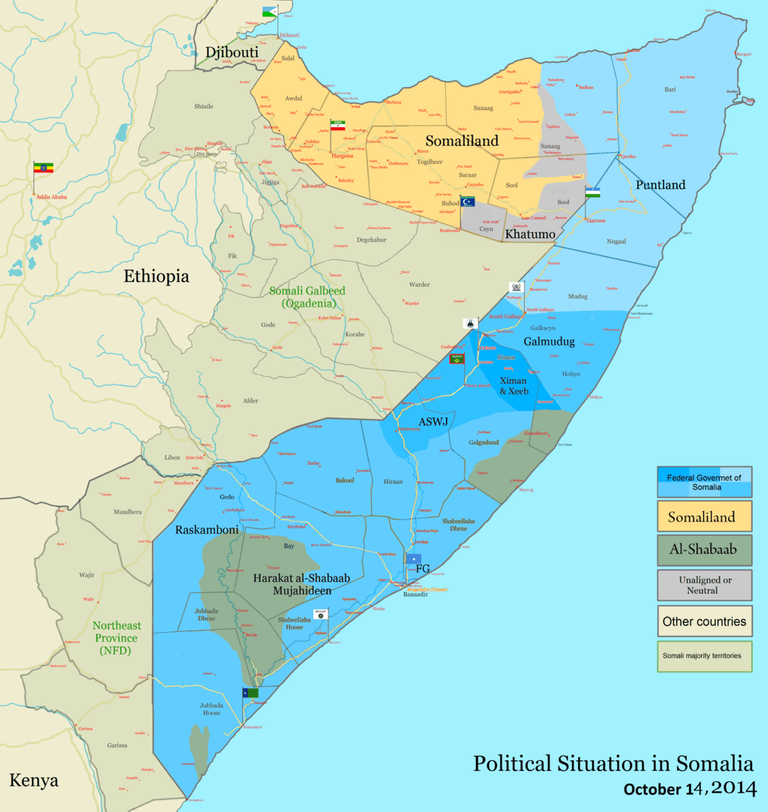

On another occasion, I had suggested to one of my business colleagues in Nairobi, the Managing Director of CALTEX (a major U.S. oil marketing company) that there was considerable business to be done in Somaliland. Somaliland, the northern part of Somalia, had declared itself an independent nation and was trying desperately to get recognized internationally as such, so it was doing everything possible to attract foreign businesses into the “country” to give it a degree of legitimacy. One of our clients, an Englishman, had (or thought he had) a contract to manage the port at Berbera on the eastern coast of the “country”. It was a deep water port that had excellent fuel storage capacity (historically having served as the principal entry point into the country for oil imports). We met with the President of the self-declared nation, Mr. Egal, on a couple of occasions to pursue this deal and were advised to carry on—remember, nothing, nothing is ever what it seems to be. I managed to convince the Managing Director of CALTEX to meet us in Berbera. My client, his agent in Somaliland, and I drove down to the coast from Hargeisa, the capital of the self-declared, independent nation. It was a rather dusty, but uneventful drive; except, of course, for the teenagers manning the all too frequent roadblocks. Here you had 14 and 15 year olds, armed to the teeth with AK-47s and, by midday, drugged to the hilt from chewing “kaat”, the local narcotic. It can be a bit scary.

My CALTEX friend flew up from Nairobi in a private plane chartered for the day—ah, the luxuries of big, American business!

Now, everything, everything in Somalia (or Somaliland, for that matter) is done by, for, and through the “clan”. And, guess what; the clans were warring over who exactly had control and, therefore, the ability to contract out the management of the port. To shorten a very long story, CALTEX found that the legal uncertainties were just too much to deal with—especially because prior to the Siad Barre takeover, Mobil Oil had controlled the port facility and CALTEX had obvious concerns about any actions Mobil might decide to take in the event CALTEX had decided to go forward. I must tell you that it was, and I suspect is, a beautiful port. The oil storage facilities were first rate and the dock extended far enough out into the harbor (we actually walked out on to it just to make certain) to permit ships with large drafts to dock and pump fuel into the storage tanks.

But, I am getting away from my story. By now, it was late afternoon. We (our client, and his Somaliland agent) had two choices. We could take several hours to drive back to Hargeisa, or fly to Nairobi courtesy of my CALTEX buddy. Well, I can tell you how I voted; not to mention our client. The problem was the Somali agent. You see, by that time, Somalis had become “persona non grata” in Kenya. Due to the civil war in their country, they were migrating in droves to Kenya and bringing with them weapons that they were trading for food. Violent crime was on the increase and Somalia was blamed. The pilot of the chartered aircraft advised us against bringing the Somali agent to Nairobi, fearing that he would be forced by the immigration officials to fly him back to somewhere in Somalia (which had not been uncommon) and was quite insistent that he could not accompany us back to Nairobi. Our Somali friend had international travel papers and I, for one (still in my period of American naivte), was convinced that with his papers, surely he would be able, in one form or another, to get into Kenya for a short period. We prevailed on the pilot and flew to Nairobi, landing at Wilson Airfield, one of the busiest airfields in Africa for general aviation traffic. Well, I had been wrong in my conclusions.

Upon arrival, we were greeted by two of the most disagreeable immigration officials I have ever had the misfortune to meet. They would not budge and wanted to incarcerate the Somali agent, and then send him back to Somalia at the soonest possible time. Not surprisingly, my client was beside himself, so I insisted that we call the Chief Immigration Officer on duty. He was at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA), the international airport in Nairobi. A van suddenly appeared and we were whisked off to JKIA. Once we arrived, the waiting began. The Chief Immigration Officer indicated that he would have to speak with THE CHIEF IMMIGRATION OFFICER (CIO) who was not at home at the moment. So, we waited, and we waited and we waited; if nothing else, Africa teaches you patience—much has been lost by a man losing his temper in Africa! Periodically during our wait, I would go in to see the Immigration Officer to see what, if anything, he had learned from the “CIO”. Finally, I could take it no longer. It had been a very long day, it was after 12:00 in the evening and all I could think about was getting to bed. So, I went in to the Immigration Officer’s office and told him that I fully understood that “special” visas did have a “cost” that we would have to bear and if he would simply let us know what that “cost” was, we would be happy to settle it and be on our way. He still insisted that he had to make contact with the CIO and asked that I wait outside, which I did. Very shortly thereafter, he summoned me back to his rather grungy office, full of smiles. He indicated that the CIO had indeed approved the VISA application and we were free to go. Miraculously, a VISA for a 48 hour period was stamped into the Somali’s travel documents and we were able to leave.

When I asked him what the charge for this “special” VISA was, he simply indicated that it was whatever I wanted to pay. As I recall, I paid him 1500 Kenyan Shillings which, at the time, was about US$ 50.

Watch this space for more on hitchhiking in Somalia!

I am not only a pacifist but a militant pacifist. I am willing to fight for peace. Nothing will end war unless the people themselves refuse to go to war.

- Albert Einstein

Excellent.

Thx @irfanllah!

Hello @wise-old-man; Einstein was definitely a "wise old man"!