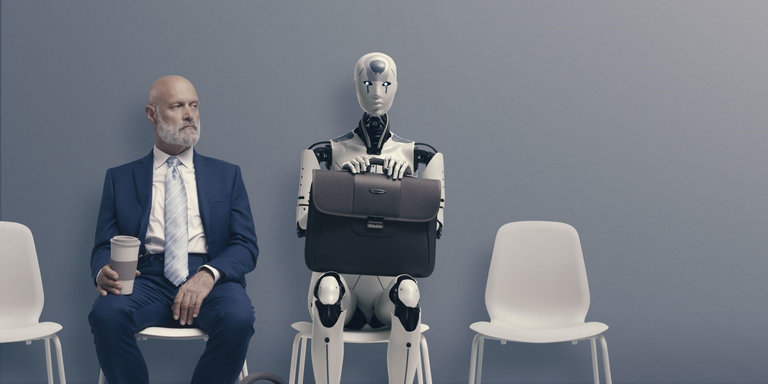

Science fiction and dystopia love to play with the concept of the fully digitalized world - one where machinery and artificial intelligence (AI) conduct all professional affairs and humans are left to their own leisure. While this has always seemed fantastical, such ideations are steadily becoming more and more possible as the underlying technology progresses. While some are excited by this idea, many others are more hesitant and raise concerns about losing their jobs and purpose; however, as Dr. Jay Richards argues in his discussion “Will Smart Machines Take our Jobs,” such a reality need not be nearly as feared as current media would have everyone believe.

Change with the Times

Firstly, it is necessary to point out that, while current society is much closer to developing a functioning AI with full human capabilities, it is still fairly far off from actually achieving it. As Dr. Richards comically points out, even the most sophisticated of AIs lack the problem-solving and intuition of an average 3-year old. Sure, AI may have incredible intelligence and ability to work out problems quicker than any normal person, but all of this is only possible through shallow mimicry. It can only analyze and churn out analyses on data it is provided - any truly generative actions are impossible in its current state (and likely will continue to be for the foreseeable future).

With regards to the job market, this means that jobs which promote further societal developments and innovations will be safe, but those that rely on programs and automated systems (such as driving, bookkeeping, etc.) are far more susceptible to be taken over by AI in the coming years. When first hearing this, many are quick to condemn the application of AI in this manner. After all, working is the only way many people can afford the costs of living, so if AI takes their jobs, they may have no means of providing for themselves, and yet, Dr. Richards has an interesting counter.

He continues to mention that this debate is the same one that has been going on for centuries, only before AI the target was smartphones, then the internet, then cars, then telephones, etc. Every innovation throughout history has displaced the industry and its workers that came before it, yet there is no mass unemployment in the modern day of developed countries, because replacement jobs have opened up in new-cutting edge industries to fill that void. The work does not simply vanish; rather, it reinvents itself under a banner of further societal growth that helps the community grow and develop. Thus, yes, AI may replace some of these jobs, but it will open the door for workers to engage in new positions that are made to fit the current technological environment, just as every other historical innovation has done. Change does not have to be feared. The only way to continue as a society is to embrace it and find your role in its wake rather than fight it, and it is in this regard that Dr. Richard’s point best shines through.

Real Vs. Artificial Humanity

With that said, there is an issue that I believe Dr. Richards does not discuss, but is a major factor in this discussion that does detract from his general idea of embracing the AI potential, and that is the concept of AI art. While not exactly taking away from traditional, salaried jobs, it does severely damage independent artists who now have to compete their commission-based work with AI art that is free and is trained off of thousands of images that are often not approved to be used by the original owners. At first, this seems once more like the natural cycle of industry displacement when a better product enters the market, as described above, but the difference between the profession of an artist as opposed to an accountant is that one deals with numbers and facts, while the other is an expression of the soul and human experience.

As mentioned previously, AI is currently developing at a rapid pace, but that is only in regards to its mimicry capabilities. Its ability to think for itself and generate new ideas is virtually nonexistent. It could readily tell me what sadness is and how it is seen, but it could not replicate the agonizing grief of death, war, loss, etc. These emotions are powerful, and talented artists have reflected their experiences with them in their works for thousands of years, weaving tales of human life, love, and tragedy. AI art is but a hollow replica of this depth, and it is deeply worrying to see it progress into these spheres that it has no place in. Dr. Richards argues that, if it is more convenient, of course it should be utilized, and while I largely agree with him, I believe the art sphere is an important exception to this generalization. It may replicate the human experience, but it cannot innovate on what it means to be alive. AI may mimic human intelligence, but it cannot, and must not, steal its soul.