In Architecture of the Divine: The first Gothic Age Dr Janina Ramirez looks back to a time when British craftsmen and their patrons created a new form of architecture.

The art and architecture of France would dominate England for much of the medieval age. Yet British stonemasons and builders would make Gothic architecture their own, inventing a national style for the first time - Perpendicular Gothic - and giving Britain a patriotic backdrop to suit its new ambitions of chivalry and power.

From a grand debut at Gloucester Cathedral to commemorate a murdered king to its final glorious flowering at King's College Chapel in Cambridge, the Perpendicular age was Britain's finest.

Traditional Architecture: An Expression of the Divine

Michael Warren Davis

Naming Prince Charles as one’s favorite Royal is rather like choosing Ringo as one’s favorite Beatle: there are no wrong answers … except that one. The Left still hold him personally responsible for Diana’s death. (It was, of course, his fault that she ran off with Dodi Fayed. And he probably got Henri Paul drunk, too.) Meanwhile, the Right sees him as too ready to apologize for the crimes of radical Islam—too infatuated with multiculturalism.

The latter’s altogether more reasonable; but, still, I have a great deal of respect for the Prince of Wales. England is measurably lovelier for having him around. If any green and pleasant land sprouts up between the dark Satanic mills, we have Charles to thank. Read any serious work on British architecture and you’ll invariably find a reference to his war against the Modernists.

Take one by Hugh Pearman from a recent issue of The Spectator, “The architectural trads are back—we should celebrate”:

Mainstream architects have tended to be a bit ambivalent about the trads, sometimes to the point of hostility. There are various reasons for this. One is that it is a style or approach beloved of Prince Charles, and Prince Charles is for ever associated with his ferocious 1980s attacks on modernist architecture, and subsequent manoeuvrings against big modernist projects.

For that, Britons—indeed, the West—owes him a tremendous debt of gratitude.

However, Mr. Pearman then makes an altogether more specious claim:

Another is classicism’s unfortunate association with totalitarianism. Hitler and Stalin famously loved this stuff, and to this day there’s a dark corner on social media where a thin, poisonous trickle of neo-Nazism still oozes through the discourse on traditionalist architecture, especially in Germany and America.

It is indeed a thin trickle—so thin, in fact, it’s hardly worth mentioning. At the very least, Mr. Pearman ought’ve given an equal hearing to the Traditionalists’ ambivalence toward Modernism, which stands more firmly on the same ground. Albert Speer, for example, is far and away our most prolific Modernist.

And, sure: Stalin dabbled in Hellenic themes for some prominent memorials and government buildings. But his greatest contributions to the Russian cityscape were undoubtedly those sprawling collectivist suburbs—the “arrogant proletarian lumps deliberately defying all concepts of beauty and grace,” forming a veritable “festival of concrete.”

The Mods aren’t bashful about this association, either. Quite the opposite. As Anthony Daniels wrote in “The Cult of Le Corbusier”:

French fascism is alive and well, and its current headquarters (as I write this) are not in the offices of the Front National but, appropriately enough, in the ugliest building in the world in the most beautiful capital city in the world, the Centre Pompidou in Paris. It is here that has been held the completely uncritical exhibition to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Le Corbusier, the fascist architect, under the title Le Corbusier, Mesures de l’homme.

Not a word about his fascism has been allowed to obtrude on the almost religiously respectful thoughts and impressions of the visitors who troop through the exhibition with solemn or pious expressions on their faces, as if regarding something holy, though what is exhibited is often so extremely bad and incompetent in execution that it should evoke derision and laughter rather than the abject mental genuflection that it does in fact evoke.

Le Corbusier was indeed an ardent fascist, but “religious” is the key word here. The politics of architecture are hazy; what one finds more commonly is that orthodox Christians are Traditionalists, whereas atheists and agnostics tend towards Modernism.

Take the viral video of Leftist students scattering before a Eucharistic procession at the University of Sydney (my alma mater). It was posted by Architectural Revival, the most popular Traditionalist social media page in English. 9,999 Trads out of 10,000 see their cause as a spiritual renewal of the West.

And, surely, it’s not a coincidence that classicism’s decline coincided with our spiritual decline.

¤ ¤ ¤ ¤

There’s always a whiff of the fear of death about Modernism—something completely absent in Traditionalist works.

Look at all the cathedrals built, in essence, anonymously. The men who created our greatest architectural masterpieces didn’t see their craftsmanship as a means of working their immortality. That process took place inside the Cathedral, in communion with the Church though the Sacraments. In the meantime, it was enough to use their God-given talents to give him glory. They were confident in their art, and in their Christ.

Modernists, on the other hand, are like those weird loners who shoot up their schools. “I’ll get them to notice me,” they growl, “one way or the other.” Blighting a landscape just happens to be quicker and easier. You can spend a lifetime tilling the earth, or an hour salting it. Either way, you’ve left your mark.

But why choose the path of destruction? Essentially, it’s a lack of perspective: a metaphysical impatience, born of despair. The loner’s 16 and have never had a girlfriend, so he thinks his love-life is basically over. It’s the same with the Modernists. Many of them no doubt could’ve been great classicists, had they taken the time and effort to master their craft. But they can’t stand waiting. They can’t risk dying without leaving their mark. They need to be famous now, even if it’s effectively infamy.

You see this theme carry through in every creative media. Take poetry, for instance. Read the major works of T.S. Eliot from beginning to end. Follow him from the youthful nihilism of “Prufrock,” to the terrible revelation of “The Journey of the Magi,” to the glorious affirmation of the Quartets. The language becomes softer and the symbolism less fitful.

As he makes peace with God, Eliot also makes peace with his own genius. Had he never converted to Christianity, he’d be a footnote of High Modernism, like his mentor Ezra Pound. (It’s worth mentioning that Pound ended his career as a propagandist for Mussolini.)

¤ ¤ ¤ ¤

Really, it’s just basic math. Classicism is associated with Christianity because it evolved while Christianity was the undisputed faith of the Western world. Its fruits stand as a cruel reminder to non-theists that the world used to have meaning, and that our lives had purpose. Church spires rose high above the townscape, pointing toward a Heaven that once bursted with saints and angels. Now the sky’s empty, except for the dark, cold stretch of infinite nothingness.

What are we to do? Why, it’s simple: tear them down. Break the mocking finger. Silence the bells that clamor into the void. Then build something else in their place—something ugly and chaotic and meaningless. Give it harsh angles to defy the smooth arches of our hollow firmament. Make it out of concrete so that it, unlike us, will never crumble into dust. Make it abominable, because there’s no One left to decry abomination.

Modernists laugh at the God that isn’t there, only because they wish so desperately that he was. The moment they stop laughing, their universe will fall silent. They’ll be left with only an icy wind moaning across eternity. Death will come to take them away, and then—nothing.

Editor’s note: Pictured above is an ariel view of Oxford University.

Tagged as Architectural Modernism, Charles Prince of Wales, classical civilization (antiquity), Sacred Architecture, totalitarianism, Traditionalists

Divine Character: The Evolution of Religious Architecture

: The Evolution of Religious Architecture

Claudio Nieto:

Since the beginnings of civilisation, the temple has been the architectural representation of society’s conception of divinity. Several of the greatest construction achievements of all times were accomplished through these buildings. Even though there are plenty of studies on this particular kind of structure, most of them do not consider time as a key element to understand the refinement sequence the temple has experienced. In consequence, this research is primarily based on Julien-David Le Roy’s Plate 1 from The Ruins of the Most Beautiful Monuments of Ancient Greece, which acknowledges the chronological development of temples as the appropriate way to grasp how these buildings evolved. At the time the plate was published, it caused a major revolution on how ‘type’ in Architecture was understood, given that it actually recognised the relevance of ‘time’ for a building’s typological analysis. As a result, studying the plate made possible to critically assess Le Roy’s discourse and determine the accuracy of his principles. Though his analysis is more likely to be based on genre than on type, it provides relevant information about the temple’s evolution which is used as the framework to address the relationship between this kind of building and its progressive architectural sophistication. An enquiry which makes possible to observe how the refinement of the temple is directly related to the way it is occupied. As it became a more public building, it acquired a higher degree of complexity, implicating that the temple’s character is expressed through structure.

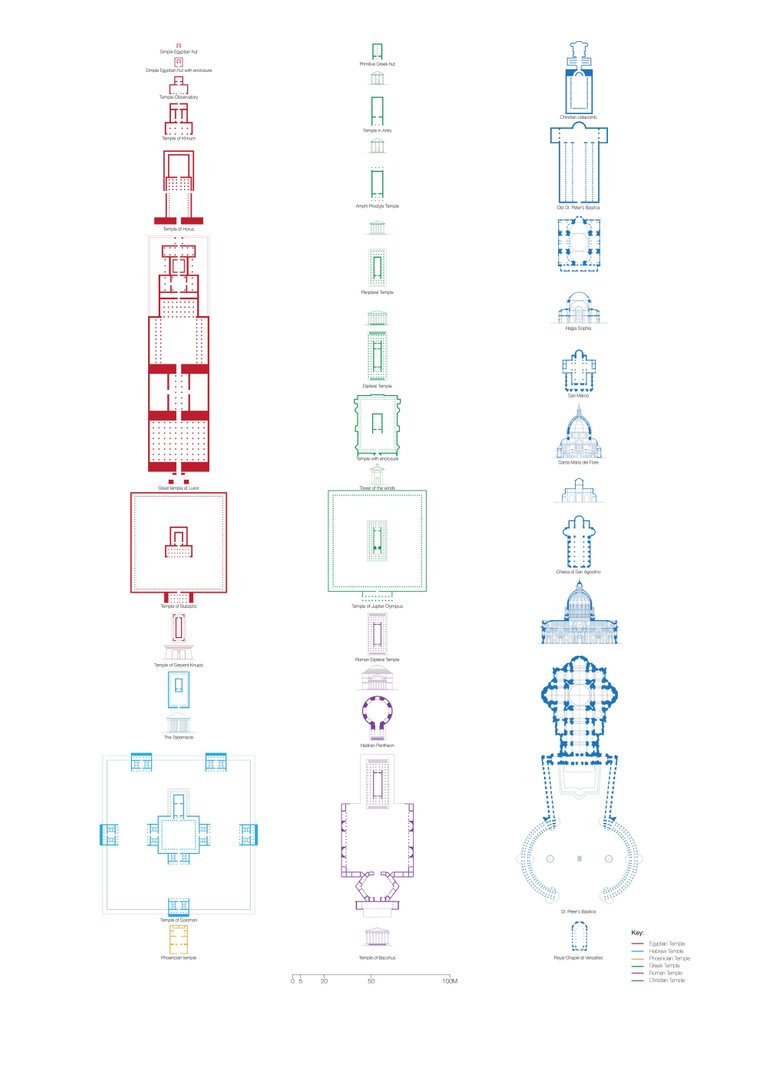

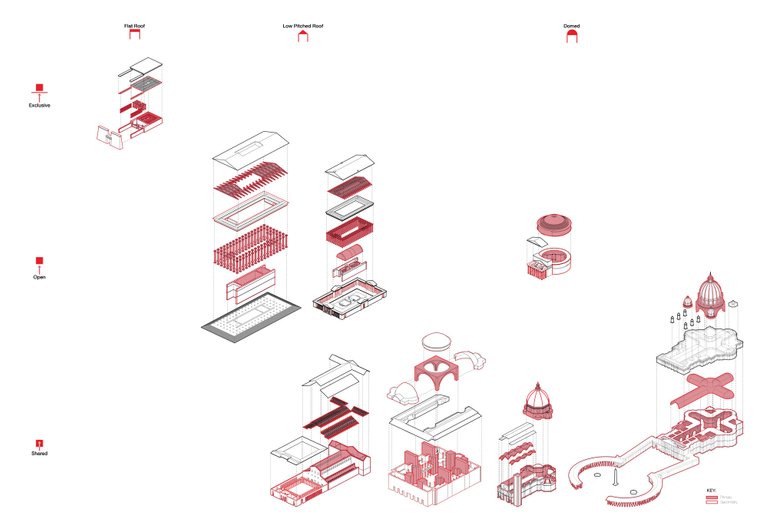

Temple classification by civilisation.

Sorted following description from e Ruins of the Most Beautiful Monuments of Greece.

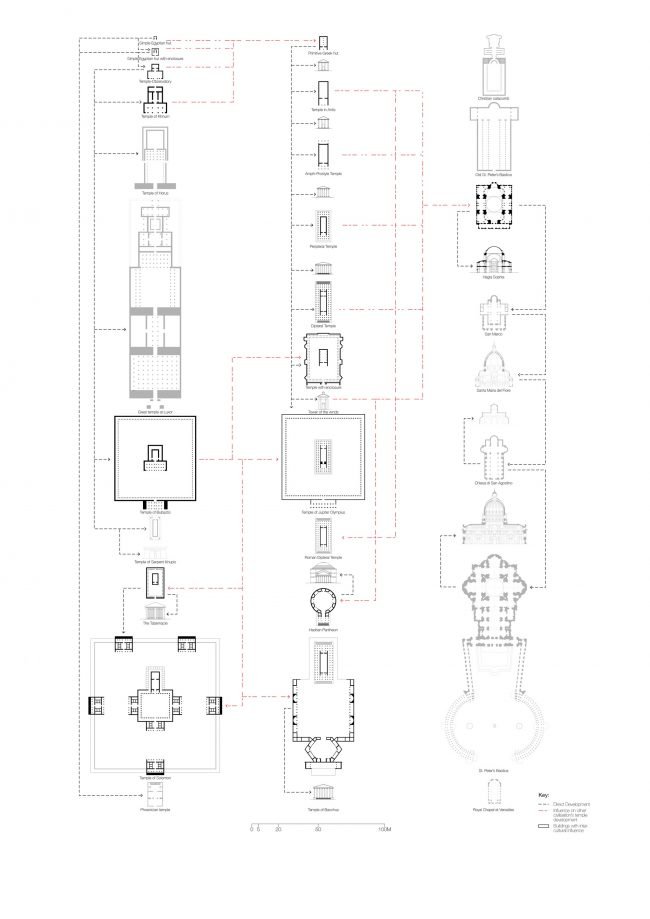

Influence exchange among temples.

Relationships and development sequence as framed in e Ruins of the Most Beautiful Monuments of Greece.

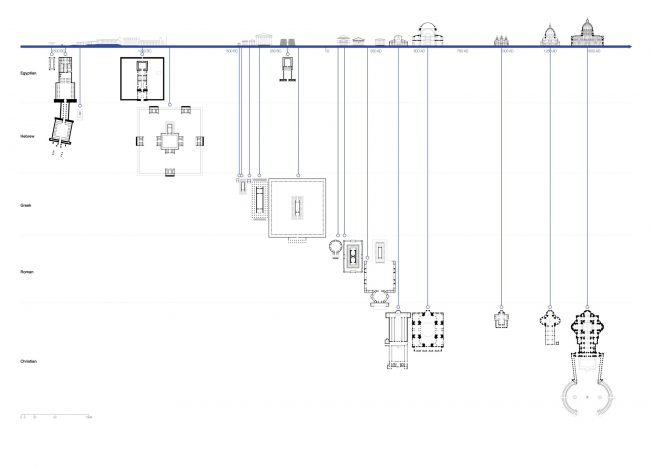

Evolution timeline of the temple.

The progressive development timeline clearly shows an increasing level of sophistication in structural systems and architectural configurations.

The origins of history and theory of architecture go back to the 18th century during the Enlightenment period. The ideological discourse of this era was founded on the idea that reasoning was the way in which people could understand the universe and therefore improve themselves. This idea and usage of reasoning was first explored by the ancient Greeks, who were considered as a model civilisation. In consequence, intellectuals adopted their heritage in order to establish the new rules of their new ideology. It was within this collective thinking that Neoclassicism as an artistic movement was born, being architecture one of its most representative expressions.1 The ways in which architecture was taught and practiced experienced revolutionary changes – France’s Académie Royale d’Architecture became the most influential school of architecture in Europe. Also, many expeditions to Greece took place at the time. Normally, all the information gathered within these expeditions was later organised and published in books. Among others, Richard Pocoke’s A description of the East and some other Countri , Frederic Louis Norden’s Voyage d’E pt et de Nubie, James Stuart & Nicholas Revett’s The Antiqu of Athens, and Julien-Davide Le Roy’s The Ruins of the Most Beautiful Monuments of Ancient Greece (also referred as The Ruins), embody the effort to explore, study, and share with the world the main source of the time’s ideology.

Many of the books written about this topic focused their narrative on the classic orders and how to use them properly.2 However, Le Roy offered a new vision on the subject, a vision which would cause a major revolution, he built an argument based on the relationships that all the buildings he registered had between them, giving less priority to the accuracy of the drawings. This position caused a lot of controversy, his competitors did not receive it in a positive way

and tried to affect his career in several ways. On the other hand, French scholars considered the discourse revolutionary and rewarded Le Roy with a position in l’Académie Royale d’Architecture. His work would later influence very important figures such as Jean-Nicolas Durand, Sir John Soane and Quatrèmer de Quincy.3 It was until the second edition of The Ruins (1770) that the Comparative Plate of Temples – Plate 1 – appeared. The use of this kind of drawings was not new at the time it was included in The Ruins (Figure 1-1). For instance, Jacques Tarade, in 1713, made several plates comparing St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and Notre Dame in Paris. Le Roy first used the plate when he published Histoire de la disposition et d form di érents que l chrétiens ont donné à leurs templ (also referred as Histoire). He made a historical analysis on the evolution of christian churches. His first approach to this kind of representation got expanded and perfected afterwards in the second edition of The Ruins. Plate 1 strengthened and presented in a far clearer way what Le Roy’s ‘Essay on the History of Architecture’ stated since the first edition of the book. A couple of decades later.

Perhaps the reason behind the great success and influence that Le Roy’s Plate 1 achieved is that it constitutes one of the first studies of Architecture through type. It had something that its predecessors did not, it was drawn following two ideas: first, the comparative layouts that evidenced architectural elements as well as design premises, and second, the chronological display through three progressive columns.4 Moreover, the two driving ideas combined explained the relationships between the buildings, and how Architecture evolved from a simple hut to a highly refined church. As Robin Middleton’s Introduction to the contemporary version of The Ruins expresses:

The new plate illustrating the historical evolution of sacred architecture now has three distinct lines of development: the Phoenicians, the Egyptians, and Hebrews are in one track; the Greeks and Romans in another; the Christians in a third. The aim, though unstated, was to separate the Greeks from the Egyptians and to distinguish the Christians from all the rest. However, the lines of development do follow on, one from another. Continuities are indicated.5

In summary, the ideological discourse of the Enlightenment, together with the collective effort by intellectuals of the time to understand the architectural principles of the ancient world, set the perfect scenario for comparative plates to thrive as the standard mean for analysing architecture. Le Roy’s Plate 1 constitutes a major reference of architectural history and theory during the 18th century, and, according to him, it focuses on the type of building that holds the highest level of perfection and produced the finest innovations in architecture: the temple.6 The plate is taken as the starting point for this research, revising, correcting and completing it. Afterwards, selected case studies, taken from it, will be analysed in detail in order to assess Le Roy’s discourse and study the relations between the selected buildings through a type and genre perspective.

The concept of type, as described by Quatrèmere, did not exist until de early 19th century. Therefore, Le Roy’s Plate 1 was no subject of any defined notion of this idea by the time it was produced. Perhaps the plate would have been quite different if a proper conception of type had existed. By analysing Plate 1, the first thing to be pointed out is that it constitutes a study of genre. Nonetheless, at the same time it includes several groups of buildings that can be considered as types, such as the basilica or the cross-plan church. This overlapping of concepts is what makes Plate 1 such a remarkable architectural study and, at the same time, it is what Le Roy failed to acknowledge in his discourse, being the major cause of its inconsistencies. Attempting to define temples of several eras and civilisations as a single type of building is a very difficult task, considering that its architecture changed drastically as it followed different religious logics. However, studying the plate through a genre perspective, clearly identifying all the types contained in it, allowed to identify the typological problems of each type which contributed to the overall sophistication of the temple.

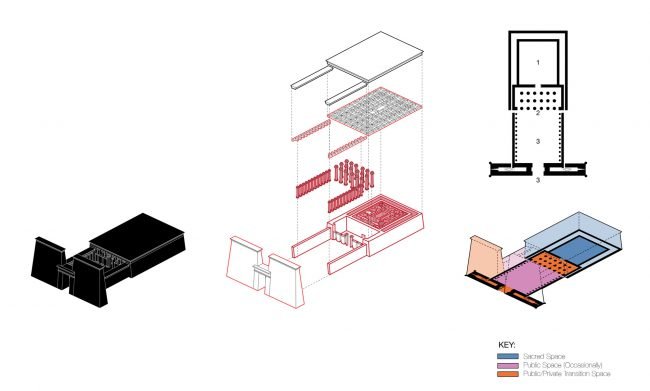

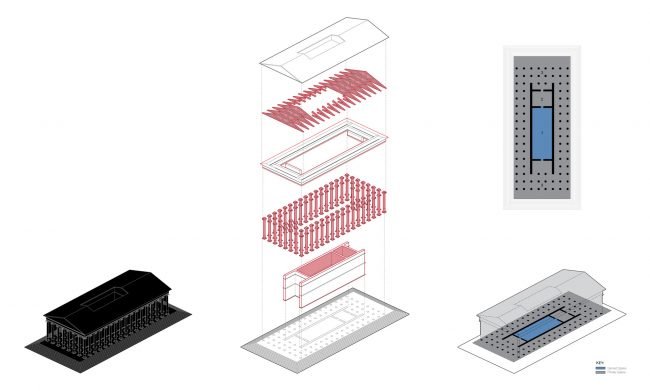

Temple of Horus: Massing, Structural analysis, Programmatic analysis

Temple of Artemis Ephesus: Massing, Structural analysis, Programmatic analysis

Old St. Peter’s Basilica: Massing, Structural analysis, Programmatic analysis

St. Peter’s Basilica: Massing, Structural analysis, Programmatic analysis

The c omparative analysis reflects that case studies share some common characteristics between them. Yet, these aspects do not work as a rule and therefore cannot be defined as a characteristic of type. For instance, the precinct is an element present in almost all the cases, but it must not be considered as a characteristic of type by itself. In this particular case, a gathering space adjacent to the temple would be a typological problem, an element that was sometimes addressed in an urban scale rather than with an enclosure. Therefore, analysing the urban emplacement of the temple would make possible to detect and understand more of its typological problems. By taking Le Roy’s methodology as the framework for research, the relationship of the buildings with the city was not considered for this study. However, the analysis suggests that an extensive investigation towards this matter would provide a deeper understanding of the temple and its role in society.

omparative analysis reflects that case studies share some common characteristics between them. Yet, these aspects do not work as a rule and therefore cannot be defined as a characteristic of type. For instance, the precinct is an element present in almost all the cases, but it must not be considered as a characteristic of type by itself. In this particular case, a gathering space adjacent to the temple would be a typological problem, an element that was sometimes addressed in an urban scale rather than with an enclosure. Therefore, analysing the urban emplacement of the temple would make possible to detect and understand more of its typological problems. By taking Le Roy’s methodology as the framework for research, the relationship of the buildings with the city was not considered for this study. However, the analysis suggests that an extensive investigation towards this matter would provide a deeper understanding of the temple and its role in society.

Comparative analysis of structural systems

Above all, despite there are several architectural types involved in the analysis, it is possible to identify a common typological problem among them: the quest for the most possible sophisticated roof. This ‘problem’ produced more advanced and complex architectural elements throughout the evolution sequence of the temple, being the driving idea behind it. Furthermore, the classification of buildings by their ritual performance made possible to identify the reasons that caused this constant typological problem. From the analysis, two outstanding concepts that thrived though the temple’s development history shall be pointed out, symbolism and sophistication. As religious rituals evolved and became more public, symbolism and sophistication increased, being the first one expressed through the parti and the second one through the structure. In other words, it can be concluded that the parti is the mean by which the temple reflects its religious and symbolic significance, while the structure is the mean for expressing its character.

Bookmark the permalink.

These diagrams are amazing. Had to resteem

ThaNks