Would you think differently about a work of art if you knew it depicted a slave owner? New labels installed at the Worcester Art Museum are drawing attention to the connections between art, slavery, and wealth in early America.

John Singleton Copley, “Lucretia Chandler” (1763), oil on canvas, Copley was one of the Boston area’s most prominent painters and painted this portrait of the daughter of a wealthy New England judge named Lucretia. The new signage at the Worcester Art Museum now notes that Chandler’s father, Judge John Chandler II (1683-1762), owned two slaves that he left to family members upon his death (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

WORCESTER, Mass. — On previous visits to the Worcester Art Museum, I had paused to consider the reserved posture and elegant dress of Lucretia Chandler Murray; however, I had not ever considered where her wealth and privilege came from — until now. While the older museum label for the portrait had underscored the characteristic style of 18th-century painter John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) and pointed to his allusion to styles adopted by the British nobility, a new label now caught my eye. It informed me that Lucretia’s father owned two enslaved persons whom he later left in his will to family members. One was named Sylvia and the other Worcester. While Lucretia’s father and husband had the financial means to pay for Copley’s talents, their enslaved persons did not.

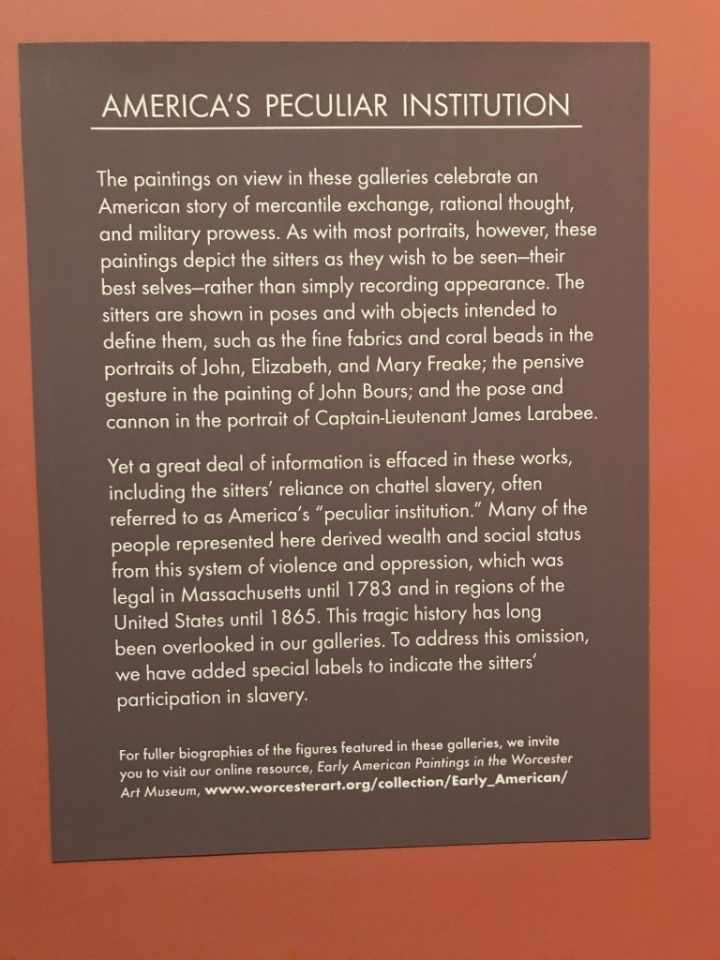

As the Worcester Art Museum (WAM) in Worcester, Mssachusetts is exploring, the signage that accompanies a piece of art is often the lens through which we view it. The WAM and some other US museums are exploring exhibit labels as an important means of contextualizing the wealthy patrons of art from the country’s past for a contemporary audience. For the WAM, that past includes portraits of men and women from both the North and the South depicted in antebellum art who either owned enslaved persons or benefited from the institution of slavery.

While wall labels in a museum’s permanent collection are often standardized, unchanging, and overlooked, curators at the WAM began to reconsider them in the wake of political and social shifts in the current era. Following the 2016 presidential election, Elizabeth Athens, a former curator of American art at WAM who is now a postdoctoral research associate at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, began to see the galleries of American art differently.

“Honestly, the catalyst for the project was the 2016 presidential election,” she explained. “While I had already been exploring ways to make the museum’s American portrait galleries more relevant to contemporary viewers, after the election I found them almost unethical in the way the labels sidestepped the less positive biographical elements of some of these subjects. While the historical labels were kept in place, a darker-colored label was added that pulled on research done by scholars studying slavery in early America, as well as the archival work of Athens and others connected to the museum.

As Athens remarked in her comments to Hyperallergic, the omission of people of color was a silence that she believed could be addressed with text. Athens was inspired by projects like Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum exhibit in order to address their absence. In 1992, Wilson had re-contextualized the Maryland Historical Society’s collection by hanging a sign outside that noted that “another” history was to be presented and then emphasizing the absence of African Americans in the collection. Wilson’s work drove Athens to reassess WAM’s collection and to address “ the complete erasure of people of color, both in the objects displayed and the way the objects were addressed.”

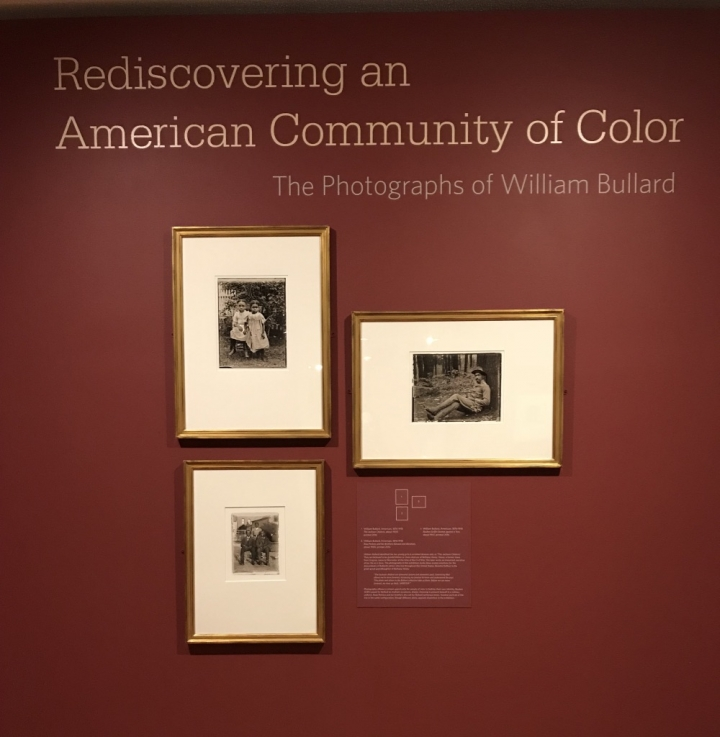

The WAM has a long history of displaying work focused on black communities in and around Worcester from the last century. A recent exhibition highlighted the photographs of William Bullard, a white photographer who between 1897 and 1917 took thousands of photos of Worcester’s black community. However, like many museums in the US, WAM’s permanent collection has no paintings by — nor featured — people of color from this early historical period of colonial America. Like Wilson’s exhibition over two decades earlier, Athens wished to address the absence of people of color in the early American art collection, viewing labels as an effective act of restorative justice: “the relabeling project helps point out that [enslaved persons] were very much there, even if we don’t see them visually depicted. This is also why I tried to identify enslaved people by name whenever possible.”

Historians of slavery like Orlando Patterson and others have noted the depersonalization that occurred in slave systems. Removing a person’s name was a means of erasing their identity and imposing a “social death” that transformed enslaved persons into property rather than living individuals. Both historians and museum professionals have begun to realize the need for revising the way we frame and label the past, and to support this movement within museums.

Deborah Whaley, a professor of American Studies and digital humanist at the University of Iowa, noted in an interview with Hyperallergic: “I think that foregrounding the accomplishments of some individuals in history has previously meant that acknowledging their complicated and racist past was ancillary. However, it is vital that we see historical figures in their complete complexity, even if it encompasses a hidden history that is antithetical to their democratic facade. I applaud curating practices that foreground the totality of the historical record — a practice that demands rhetoric for freedom — in writing and speeches — matches material practices in everyday life.”

It is indisputable that between 1619 and 1865 slavery existed and thrived within the United States. The institution provided considerable wealth for families in both the North and the South, even in cases where Northerners did not directly own a slave. Daina Ramey Berry, an associate professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved from Womb to Grave in the Building of a Nation, has tracked the monetization of African American enslaved persons in her work.

In her book, Berry follows slaves through their life cycles and prices out their financial contribution to slaveholders. She also analyzes how slave labor benefited the broader economic networks in antebellum America. In an interview with Hyperallergic, Prof. Berry noted that she too believes that the Worcester Art Museum’s actions can restore knowledge of America’s history of slaver. “I was happy to see that the art world is expanding into recognition of slavery through signage. It not only reinserts black people who could not afford [to have their portrait painted], it also makes us question who is celebrated in museums and in society.”

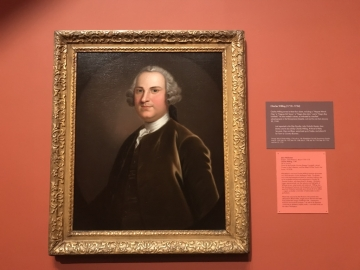

The economic benefits of slavery are now explicit on the labels at WAM. Beside a painting by John Wollaston of Charles Willing (1746), a newly added label notes that the Philadelphia merchant owned four slaves. Using a copy of Willing’s will and articles from the Philadelphia Gazette, WAM invites viewers to grapple with the fact that Willing owned: a “Negroe Wench Cloe,” a “Negroe Girl Venus,” a “Negro Man John, and a “Negro Boy Litchfield.” These facts make it harder to deify eighteenth and nineteenth century New Englanders and profoundly alter how we view the portrait.

Museum educators and curators are indeed taking note and remarking on the racism that has plagued museums in the past and in the present. Juline Chevalier, the Head of Interpretation and Participatory Experiences at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, noted to Hyperallergic: “Legacies such as racism, colonialism, and white supremacy are systemic forces that create the basis for all aspects of contemporary US society and culture, so of course, they show up in museums. These are systems that have privileged and prioritized white bodies and artists, heterosexual and cisgender identities, the male gaze, the ‘western’ cannon, academic research over lived experience, and on and on. It can be difficult for those of us who are favored by these systems to see them for what they are — inequitable.”

Museum educators and curators are indeed taking note and remarking on the racism that has plagued museums in the past and in the present. Juline Chevalier, the Head of Interpretation and Participatory Experiences at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, noted to Hyperallergic: “Legacies such as racism, colonialism, and white supremacy are systemic forces that create the basis for all aspects of contemporary US society and culture, so of course, they show up in museums. These are systems that have privileged and prioritized white bodies and artists, heterosexual and cisgender identities, the male gaze, the ‘western’ cannon, academic research over lived experience, and on and on. It can be difficult for those of us who are favored by these systems to see them for what they are — inequitable.”

As Chevalier remarked, these biases are not limited solely to labels, “These systems show up in many ways. Whether it’s a tour guide avoiding calling on a child in their group because their name is ‘too difficult’ or the fact that American Art and Native American Art are two distinct departments in most encyclopedic museums. Exclusionary frameworks and systematic bias manifest at museums in all aspects of collecting, planning and presentation of art and artifacts.” Labels are an integral part of enlarging and questioning our framing of the past.

I must admit that I am anecdotal proof that this new signage has an impact. I am not an expert in American art — I usually go straight to the ancient mosaics at WAM. But I was struck hard by these new labels. I am an ancient historian but also a white woman from the South who now teaches a course on slavery and marginal peoples in antiquity in a small Midwestern city. Until I read these labels, I really did not know much about how early American art in New England was influenced by slavery; like many, I tied slavery predominantly to the South. I came away with a new understanding of the accumulation of wealth that underpins the art world then and can still support it today. At the same time, I was also reminded that enslaved persons were not always invisible participants in the art world.

Unlike much early American artwork, enslaved persons and manumitted individuals freed from slavery were highly visibly within ancient artwork. This fact is frequently commented upon on labels in both European and American museums today. Only a few days after my trip to WAM, I travelled to the Museum of Fine in Boston and stood before a large late Republican funerary portrait. The relief represents a slave owner named Publius Gessius, a female enslaved person he owned and later freed in order to marry named Fausta Gessia, and their son, who was enslaved and later freed. His name was Publius Gessius Primus.

Rebecca Futo Kennedy, an associate professor of Classics at Denison University and the director of the Denison Museum, remarked on the visibility and framing of ancient enslaved persons in artwork to me, “I was thinking myself about the ubiquity of slaves in Greek and Roman visual arts — tombstones in Attica, wall painting from Rome. I wonder if slave owners in America were as comfortable with their slavery as Romans and Greeks were.” Artwork can indeed be a window into whether a culture felt shame over their participation in a slave economy.

The progressive steps taken by Athens and the WAM help illustrate the institutional benefits white America enjoyed from the work of slaves. And WAM is not alone in this effort to contextualize and address the past. College campuses like Georgetown, the University of Virginia, and Princeton University have begun to discuss their institutional connections to slavery. At Princeton, the ‘Princeton and Slavery Project’ across campus has encouraged the display of both old and new art that engages with antebellum slavery and how the university benefitted from it.

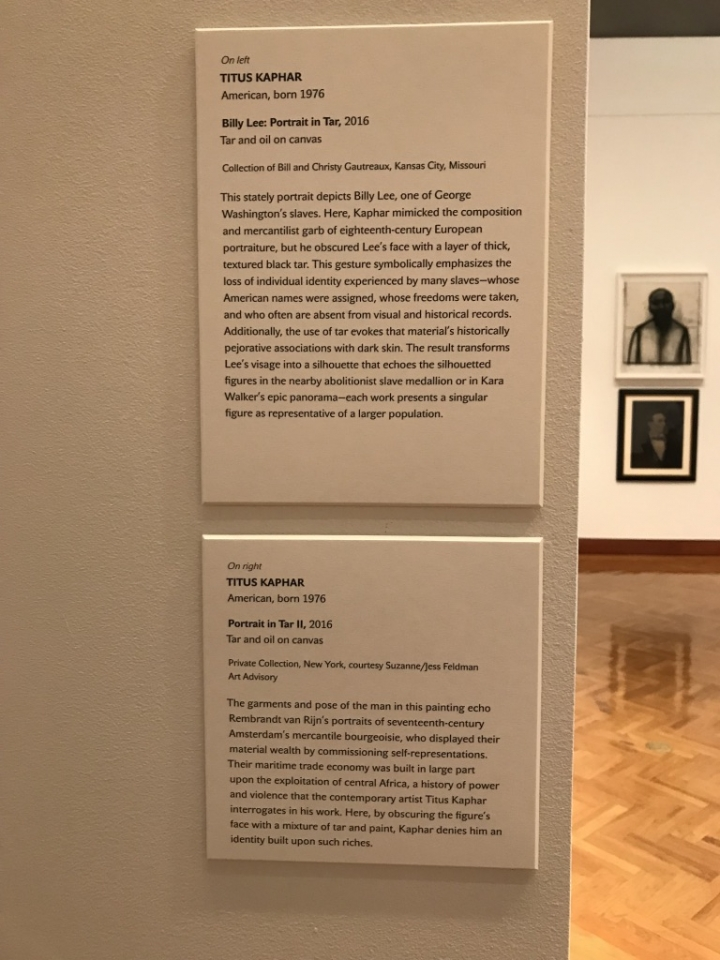

As part of the project, abolitionist art was recently displayed side-by-side next to American artist Titus Kaphar’s work at the Princeton University Art Museum in the exhibition Making History Visible: Of American Myths and National Heroes. Kaphar was also commissioned by Princeton to create a work called Impressions of Liberty. The sculpture is made of “wood (American sycamore and plywood), etched glass, sculpting foam, graphite and LED lights” and was originally installed on the site on the Princeton campus wherein six enslaved persons were sold on July 31, 1766. These individuals were once owned by Samuel Finley (1715–1766), the fifth president of Princeton (then the College of New Jersey).

William Rush, “George Washington” (ca. 1817), painted plaster, Titus Kaphar, “Billy Lee: Portrait in Tar” (2016), tar and oil on canvas, at the Princeton University Art Museum, the work of artist Titus Kaphar plays into a broader conversation about slavery on campus. Billy Lee was a slave of George Washington, which Kaphar has now put into eighteenth century mercantilist clothing, which the label notes, “emphasizes the loss of individual identity experienced by many slaves.”

In addition to WAM and the Princeton Art Museum, the newly opened National Museum of African American History & Culture has also raised the visibility of such historical connections to slavery. But it is important for museums not explicitly focused on African American heritage, such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, to address these matters in their collections. Athens, herself, is now a research associate connected to the National Gallery. She hopes that this important contextualization effort will soon have an even wider reach and inspire other museums to revise their labels.

The museum’s role in creating a micro-environment within which to experience the past has never been more apparent. Athens notes that part of WAM relabeling project was meant to address the “historical amnesia” in the North where people consistently deny New England’s ties to slavery. The new labels at the Worcester Art Museum and the work of scholars like Berry have, alongside the work of many others, demonstrate that the impact of and profit from slavery was not confined to the antebellum South.

Addressing museum labels means we must also revise the idea that museums occupy a space of “neutrality” within the national conversation. Futo Kennedy remarks, “Museums have traditionally laid claim to being a ‘neutral space’, as a repository of knowledge, their job is not to analyze or narrate that knowledge, just hold it and show it for others to interpret. They avoid issues of slavery for the same reasons they avoid dealing with their own history of complicity in colonialism. The argument of ‘public interest’ has been used widely to justify the keeping of cultural heritage objects, particularly antiquities, but also human remains. But who is the ‘public’?” As Futo Kennedy notes, museums must overcome the fear of incensed donors or angry parents in order to engage with our uncomfortable history of slavery.

White people in every part of early America directly or indirectly benefitted from the “peculiar institution” of slavery. It created wealth for white families and oppressed the African-Americans forced to perform labor in service to them. This labor allowed wealthy men and women the luxury of free time and money to get their portraits painted at a hefty price by a well-known artist. As Athens notes, museums have the power to engage with an underscore this part of American history: “I think museums can play a part in social justice movements through honest, clear-eyed reassessments of the stories they tell, what those stories privilege, and what they obscure.” Restoring people of color to American museums isn’t just about editing collections or artwork on display, it must also address the labels we have attached to them for hundreds of years.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://hyperallergic.com/439716/can-art-museums-help-illuminate-early-american-connections-to-slavery/

Congratulations @anwar0x! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP