In 1972, the critic opened our eyes with analysis of the female figure in art and advertising – in today’s frenzied image culture, his lessons are still necessary

3January 2017

TextEmma Hope Allwood

“A woman is always accompanied, except when quite alone, and perhaps even then, by her own image of herself. While she is walking across a room or weeping at the death of her father, she cannot avoid envisioning herself walking or weeping. From earliest childhood she is taught and persuaded to survey herself continually. She has to survey everything she is and everything she does, because how she appears to others – and particularly how she appears to men – is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life.”

Art critic and writer John Berger, who died yesterday aged 90, spoke these words in the second episode of seminal BBC series Ways of Seeing. Together with a shoestring budget, a shared leftist ideology and a sympathy for the burgeoning women’s movement, he and director Mike Dibb challenged the elitism of arts programming, encouraged their audience to unpick the meanings of paintings rather than simply revere them, and managed to make Walter Benjamin’s ideas about mechanical reproduction digestible in a 30-minute episode. With the series spanning topics including the role of the critic, the way art is constructed for our ‘gazes’, how it depicts women and possessions, and even the way that advertising works, it remains deeply relevant today.

But it’s Berger’s discussion of how we look at women which resonates most strongly in our current image-obsessed society. Today, the idea of the male gaze may seem well established, and Berger and his all-male team didn’t claim to invent the concept which would later be christened by film critic Laura Mulvey. But this was 1972 – the Sex Discrimination Act was still three years away, contraception wasn’t yet covered by the NHS, and it would be almost a decade before women could take out loans in their own names without a male guarantor. And yet, here they were, on one of only three channels on mainstream television, sitting in a group and discussing issues such as agency, empowerment, and their relationships to their own bodies and to men. Of course, not everyone was pleased about it – according to the Guardian, Ways of Seeing was derogatorily compared to Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book “for a generation of art students”.

“The female nude in Western painting was there to feed an appetite of male sexual desire. She existed to be looked at, posed in such a way that her body was displayed to the eye of the viewer”

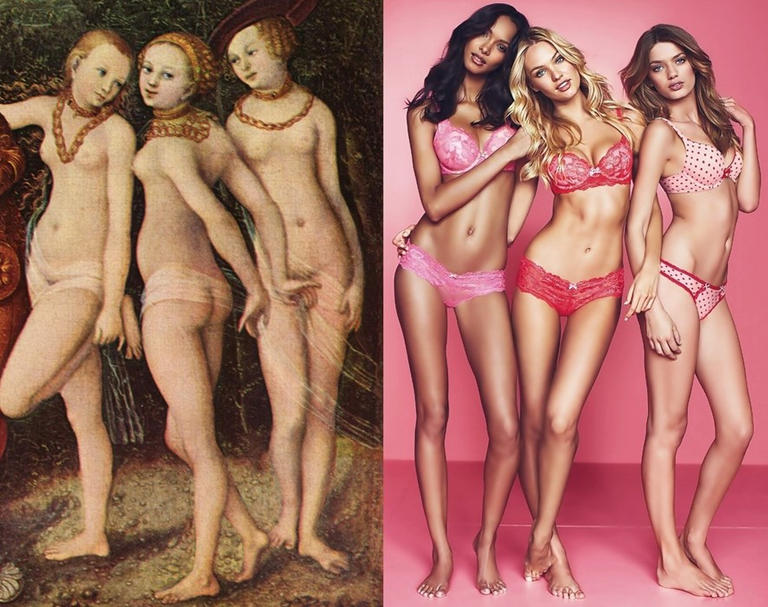

The ideas put forward by Berger and Dibb, which were later published in a best-selling book created with Sven Blomberg, Chris Fox, and Richard Hollis, were simple but radical. The female nude in Western painting – hairless, buxom, invariably with skin as white and unblemished as a pearl – was there to feed an appetite of male sexual desire. She did not have desires of her own. She existed to be looked at, posed in such a way that her body was displayed to the eye of the viewer, there only to be consumed. Of course, there was hypocrisy in this, too – “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her,” wrote Berger, “Put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting ‘Vanity,’ thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for you own pleasure.”

Naturally, the way female bodies were presented culturally as objects to be looked at had an effect on women, on the way they came to see themselves – as a sight, a vision. In the words which opened this article, Berger pins down a feeling which, although perhaps not universal, is familiar to many, many women. It comes with adolescence – maybe the first time a man yells at you from a moving car – and is the sense of living life one step removed, living as your own spectator. You are never yourself, you are yourself as you appear to others. To men, yes, and to the women with whom you are supposed to compete for their attention.

To grow up a woman in a Western patriarchal society is to be constantly analysing and critiquing your own appearance, constantly struggling with the reality of your body and the ideals with which you have been presented, measuring yourself up – not for your own pleasure but for the eyes of men. Like that moment in the first season of Sex and the City, when Carrie reveals that she’s performing a version of herself for love interest Mr Big, terrified he will see the real her and his desire will dissipate. “You should see me around him,” she explains to Miranda. “I’m not like me. I’m, like, Together Carrie. I wear little outfits: Sexy Carrie and Casual Carrie. Sometimes I catch myself actually posing. It’s just – it’s exhausting.”

In Ways of Seeing’s final episode, Berger discusses how the goddesses of art became the models of contemporary advertising, and suddenly it was no longer only men looking at images of women lustfully. Advertising tells us that buying a product will transform us by showing pictures of those who have already been transformed by it – these are people we should aspire to be like or be with. An image of an underwear model is desired by men and envied by women. “This state of being envied is what constitutes glamour, and publicity is the process of manufacturing glamour,” Berger says. “Glamour is supposed to go deeper than looks, but it depends upon them, utterly,” he says.

Glamour, envy and the act of looking – these are the foundations on which our current fashion and social media obsession rests. Consider the Victoria’s Secret Angels. A fleet of women so beautiful, so primped and preened that the name bestowed on them is otherworldly. The Angels present the ultimate female fantasy, with one donning the multimillion dollar jewel-encrusted ‘Fantasy Bra’ for her strut down the catwalk – each year held in a different global location. They are living, breathing advertisements, existing for mass consumption – the show, seen by millions of mostly women, is the most watched fashion event in the world. December’s event has generated almost 100,000 Instagram posts alone.

“Glamour, envy and the act of looking – these are the foundations on which our current fashion and social media obsession rests”

Together, with their breasts lifted, their faces contoured, their bodies waxed and their hair extended, they present a vision of Western female beauty standards so perfect that it is stunning. The Angels – who depict themselves on social media eating healthily and posting workout videos with the phrase #trainlikeanangel, and who we see undergoing pre-show make-overs in pink satin robes – have been transformed. The implication is that, through the purchase of products, the brand’s customers can be transformed too. Bounding down the catwalk, the Angels are less static than the nudes who were passive, coyly regarding their male voyeurs. But the impact remains the same – they exist to incite desire, to embody the ideal.

Of course, this is one brand – the Angels are the tip of an iceberg of imagery which makes its way into our brains via social media, television, runway shows, magazine adverts and many other outlets. The fashion industry is built on selling a female ideal, and the Angels are a strong but not singular example of this. Berger didn’t want to put an end to advertising, and he certainly didn’t want us to stop looking at classical art – but with his collaborators and a late night TV slot, he helped to kickstart a quiet revolution in the way we view the world around us. He encouraged us to question the images which have been the foundation of our culture. That is a truly worthy legacy – and one we must continue.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/34166/1/why-we-still-need-ways-of-seeing-john-berger

Congratulations @differentlysmart! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!