The international market of works of art is littered with fakes, and some are so convincingly that even specialists are deceived. Gone are the days when it was impossible to distinguish a fake from the original. Now the appearance on the market of an unknown masterpiece immediately raises suspicions. In addition, scientists have a whole arsenal of the latest technical means with which you can explore even the most insignificant quantities of paint components.

At all times, ranging from the great Flemish painters, Venetian and Florentine masters of the Renaissance and to contemporary artists, works of art have been the object of fraud. In 1989, the heirs of the French artist Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955) sued the art dealer in the city of Bourg-en-Bresse (France). They expressed doubts about the authenticity of the picture, supposedly owned by Utrillo's brush, which was put up for sale for 1.8 million francs (about 360,000 dollars). The canvas was given for examination, and experts were convinced that this is a fake.

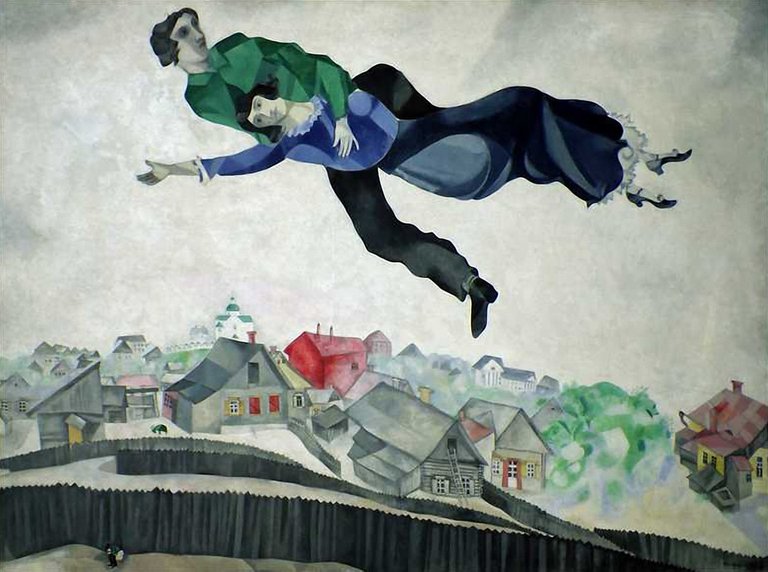

The police figured out who was behind the fraud. He was a Frenchman who lived in the United States. In France he was helped by his nephew. During the search at the Blois house, the state prosecutor confiscated a number of canvases allegedly owned by Utrillo, as well as copies of paintings by Marc Chagall (1887-1985), Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) and Raoul Dufy (1877-1953).

For a long time, the trade in counterfeit works of art flourished, and incomes were estimated at many millions of dollars. This flourishing flourished in the twentieth century. Now it also covers sculpture, carvings, ceramics and tapestries. Often counterfeit works of Oriental art, as well as pre-Columbian art objects of America.

Question of competence

It's no secret that museums store and display fake works of art. In France, disputes still remain about the authenticity of paintings allegedly belonging to the brush of the Dutch artist-abstractionist Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), exhibited in the famous Pompidou Center. The confusion is aggravated by the fact that many old masters, for example Rembrandt, often attracted students to work on the picture. In some cases, paintings previously considered authored, now refer to works performed by the student or the whole collective of the artist's studio.

According to one of the famous French auctioneers, "the buyer risks being the owner of a fake. There is a large number of works, especially old masters, whose authenticity has not yet been established. The point of view of any expert can be challenged."

Even the ancient Romans were making copies of sculptures and coins to meet the demand of fanatic collectors. Later this practice spread to painting, especially during the Renaissance. However, in those days, the manufacturers of copies did not try to deceive. They sought to revive the brilliant works of art and even improve them for the benefit of their fellow citizens.

However, over time, selfish motives prevailed, and talented copyists began to sell their works, giving them for masterpieces of famous masters. In other cases, artists who did not find their own style, turned to the craft of making fakes, thus achieving recognition of the public.

Dutch master

The most famous artist-imitator of the XX century, probably the Dutchman Hans van Meegeren (1889-1947). As a student, he learned to masterfully paint and subsequently used his skill in writing copies. From 1935 to 1943 he produced 13 canvases in the manner of Dutch masters, such as Frans Hale (1581-1666), Gerard Terborch (1617-1681) and Jan Vermeer (1632-1675). Art historians considered the works of van Meegeren as originals, every appearance of the "unknown" picture of this or that famous artist became a real sensation. The canvas on the religious theme "Evening at Emmaus," written in the manner of Vermeer, was greeted with delight, as "an artistic discovery of the twentieth century." Van Meegeren sold eight of his counterfeits, mainly to museums and members of the Nazi government of Germany.

The scope of fraud was discovered only after the Second World War. Having confiscated an extensive art collection stolen by Germany's German airman, Hermann Goering, the Dutch police discovered in her previously unknown picture of Vermeer "Christ and the harlot." Initially, the authenticity of the work did not cause doubts. Investigators just wanted to find out who owned this painting, and contacted Germany. In late May 1945, the investigation led to the van Meegeren. He was accused of collaborating with the occupation authorities, but he continued to keep a stubborn silence.

Two months later, van Meegeren revealed his secret. "You, a bunch of idiots," he shouted to the investigators. "I have not sold a single treasure of art belonging to our country." These pictures I wrote myself. " He recognized his six paintings, but no one believed him. He was asked to write another picture "in the manner of Vermeer." He did so, demonstrating his art before the police officers. In late 1947, the court sentenced the master of fakes to the year of the prison. Soon after his release, van Meegeren died.

Thirty Van Goghs

In the mid 1920s, experts recognized the authenticity of 30 works by the Dutch painter Van Gogh (1853-1890). The paintings belonged to a Berlin dancer and art dealer who claimed to have acquired it from a Russian who traveled from Switzerland to Egypt. When the paintings were displayed next to the original works of Van Gogh in the German capital in 1928, many visitors thought that they looked like fakes. Viewers were right.

How to identify a fake?

On the eye, even an expert does not always manage to distinguish a fake from a genuine work of art. Therefore, today in determining the authenticity of a painting or sculpture, art experts use the services of experienced photographers, chemists, radiologists and even nuclear physicists. There are a number of methods for analyzing pigments: sometimes a pinhead-sized sample is enough to detect a fake. Radiographs of layers lying under the top layer of paint, give valuable information about the time of the creation of the painting. In exceptionally complex cases, art historians have the opportunity to use a proton and ion accelerator to accurately determine the composition of the paint and to isolate the chemical components that may be present in very small quantities.