On May 10, 1508, Buonarroti began painting for the order of Pope Julius II the impressive vault, which ended four years and five months later.

The relationship between the great Michelangelo Buonarroti, painter, sculptor and Renaissance architect (1475-1564), and Pope Julius II (1443-1513), master and protector of artists such as Rafael or Bramante, was always difficult and contradictory. The pontiff commissioned the Divine, as it was called, the execution of several works, of which the most famous and marvelous would be the frescoes that decorate the vault of the Sistine Chapel (Vatican City, Rome); He deeply admired his talent and for that reason allowed him - something unusual at the time - to choose the images and carry them out with complete freedom. But, on the other hand, their arguments and fights were constant, because of differences of opinion about the speed of the work and, more frequently, for matters of money.

His first disagreement was due to the first of these papal orders: in 1505, Julius II proposed to Michelangelo to design and build his sepulcher. The artist, enthusiastic, considered it as the work of his life, but he could never finish it because of the changes of opinion of the pope (although one of the greatest sculptural jewels of all time, the Moses -which today can be seen in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli of Rome-, was originally part of the burial). Precisely one of those papal lurches was that he left the tomb to devote himself to decorating the fresco of the vault of the Sistine Chapel. Buonarroti accepted with two conditions: he would start from scratch-Brántante had placed some scaffolding that he replaced-and he would work alone (he rejected the collaboration of experts in frescoes, a technique he did not know, so he had to repeat part of the work, this time advised , for problems with moisture, salts and running time). And so, with the approval of his master, he went to work on May 10, 1508.

The chosen theme was a Neoplatonic interpretation of nine scenes of Genesis, surrounded by the twelve prophets, the sibyls and other figures framed in a great painted architectural structure, inspired by the real shape of the vault. The four years and five months of work were a technical nightmare and physical resistance - his eyes were severely damaged by the paint that fell on his face, to execute much of the work lying on the scaffolding, and the same thing happened to him on the back and neck - but the result, which was presented to the public on October 31, 1512, is dazzling; in the words of Goethe, when contemplating the vault "one can understand what the man is capable of". And that was not the end of Michelangelo's involvement: years later, at the request of other pontiffs, he agreed to paint the altar wall of the Chapel with another colossal work: The Last Judgment (1536-1541). Here are some details of both jobs.

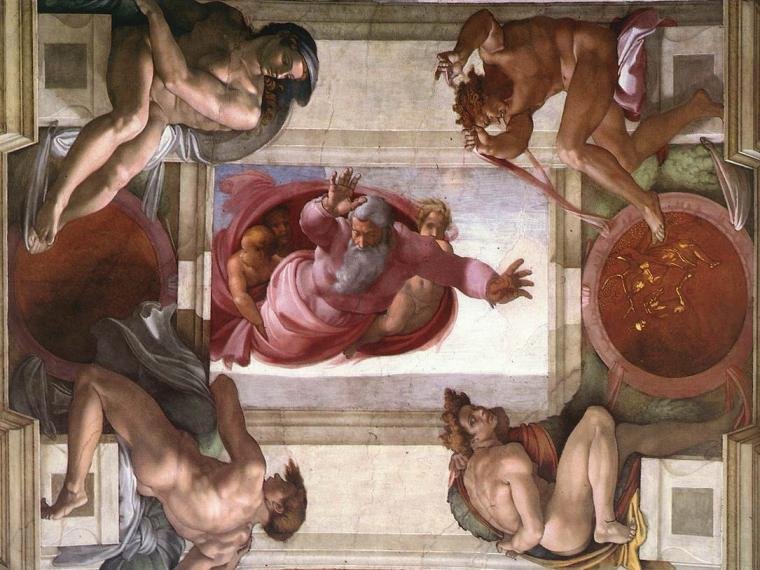

1. The creation of the stars and plants

In this scene, the third and fourth days of creation are represented: the figure of God on the back creating the plants and the front (in the image) creating the stars. That dual divine presence, so dynamic, alludes to the omnipresence of the creator.

2. The separation of water and land

Here we see God flying with outstretched arms, to show the energy of his hands, and thus order the separation of waters and earth. The perspective and the architectural structure of the scene are masterful.

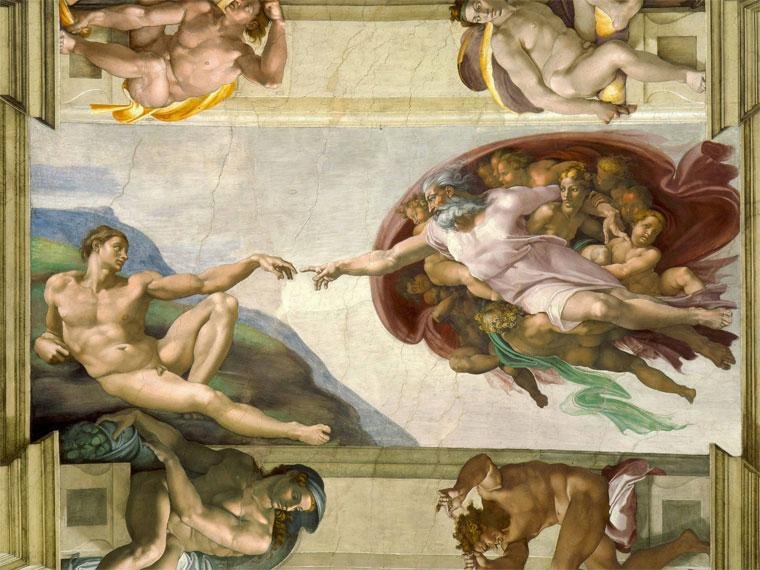

3. The creation of Adam

It is the central and most famous scene in the entire vault. Nobody like Michelangelo has been able to capture the creation of human life with such simplicity and strength, through the transmission by contact of the fingers, as if it were an electric current. And his Adam has remained as a Renaissance icon of masculine beauty.

4. The figure of the creator, God

In that same fragment, there is a contrast between the spherical structure of the mantle that surrounds the creator, accompanied by the angels, and the lengthening of the line of his body towards Adam: his figure thus overflows with energy and a violent dynamic.

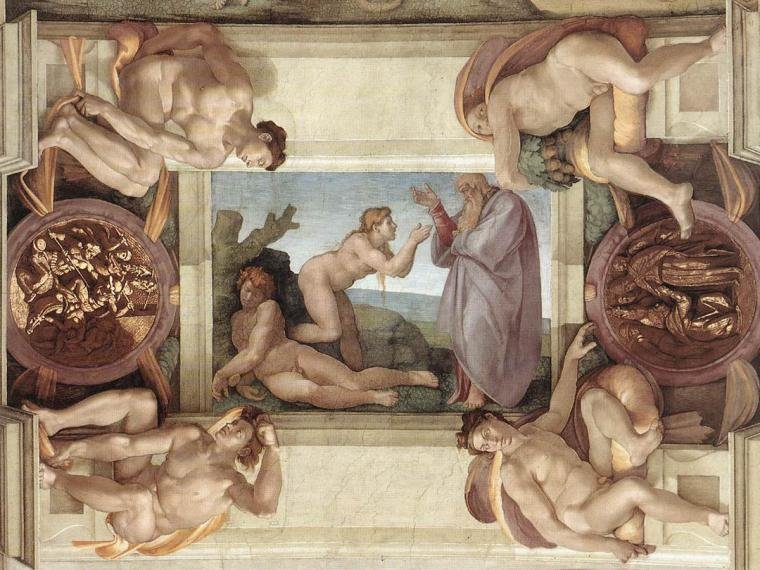

5. The creation of Eve

From the side of Adam, Eve enters with her hands in a position to pray to God. His nakedness is devoid of seduction: the body has a great heaviness and the face is made with thick strokes similar to those of a Roman matron.

6. The expulsion from Paradise

This is the right fragment of the scene; on the left, Adam and Eve's fall from grace is shown for disobeying God and eating the forbidden fruit. The balance and twist of the figures is of an absolute anatomical perfection.

7. The eritrea sibyl

Prophets and sibyls occupy the triangular spaces and are the largest figures in the set; they represent the hopes of humanity before the coming of the Messiah. The sibyls are five: the Cumana, the Delphi, the Libyan, the Persian and the Eritrea.

8. The prophet Daniel

This was one of the figures most critisided of the restoration carried out between 1980 and 1989. Put up severe objections, arguing that what he gained in luminosity and voluptuousness lost it in depth and contrast.

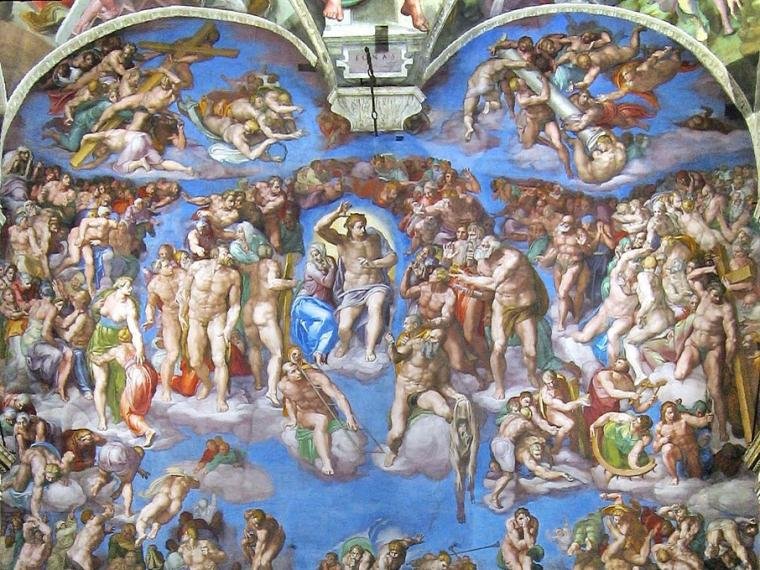

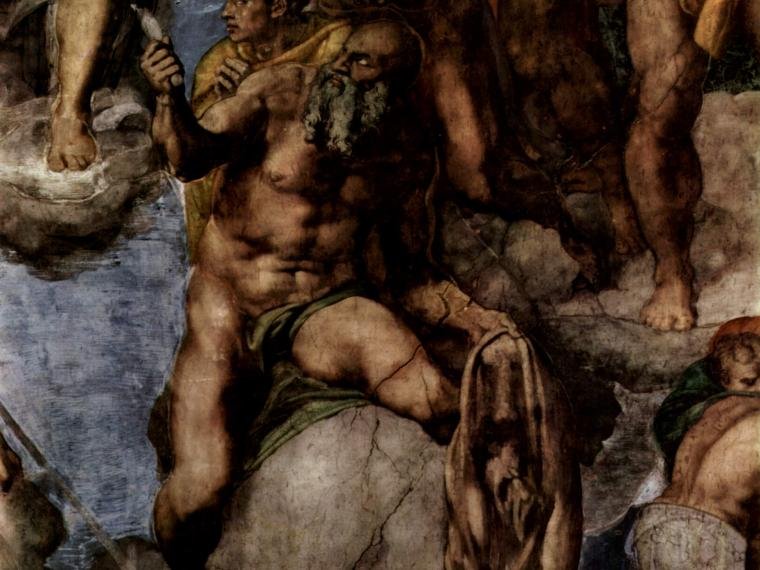

9. The Last Judgment

The other great fresco by Buonarroti in the Sistine Chapel; in this case, it occupies the wall of the altar. The theme is based on the Apocalypse of Saint John, also with a Neoplatonic interpretation and a very vibrant performance.

10. Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary

The central part is occupied by a Hellenic Jesus with an energetic gesture, which separates the righteous from the sinners; next to him is his mother, Mary, who seems frightened by the violent gesture of her son.

11. The souls of the saved

Both appear surrounded by a multitude of characters; among them, on the right side of Christ, those who ascend to heaven after the Last Judgment. The aerial composition of this area of the fresco is spectacular.

12. Charon and the condemned

In contrast, on the left side of the painting are the condemned who descend into the darkness, some of whom are on the boat of Charon, the character present in Dante's Divine Comedy

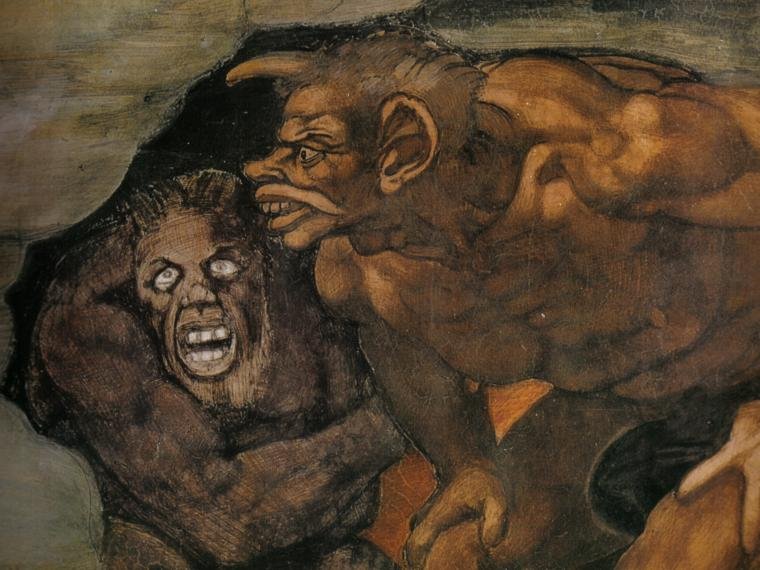

13. The demons

Angels appear in the semicircles of the upper part of the mural; another violent contrast with the monstrous demonic figures we see in this detail from the bottom of the fresco.

14. Saint Bartholomew

Also, around Jesus are the saints, easily recognizable as most show the attributes of their martyrdom. Among them St. Bartholomew, who was skinned; The saint has his own skin hanging by the hand, where Michelangelo's self-portrait can be seen as a signature.

15. Michelangelo and Volterra

And speaking of portraits, this one of the great Buonarroti, one of the most famous, is due to his disciple and collaborator Daniele da Volterra, who nevertheless has gone down in history for accepting to cover the nudes present in the Last Judgment with cloths and clothes, what earned him the satirical nickname of il Braghettone.

@misterioyciencia you were flagged by a worthless gang of trolls, so, I gave you an upvote to counteract it! Enjoy!!