In order to understand the photographs of Joel-Peter Witkin, one must understand some basic definitional information about those who are considered “disabled.” The term disability, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, has several currently active definitions. The first definition is a simple outline of the effect of disability, as “Lack of ability (to discharge any office or function); inability, incapacity; weakness.” This meaning is referring to an individual person’s capability to perform physical and mental tasks, but is lacking the personification of the expression. The next entry in this dictionary slightly expands on the ideas presented in the first, “A physical or mental condition that limits a person's movements, senses, or activities; (as a mass noun) the fact or state of having such a condition.” This definition brings the disability into the personal realm, there is a singular embodiment of the condition of disability. The third currently used definition of disability is, “Incapacity in the eye of the law, or created by the law; a restriction framed to prevent any person or class of persons from sharing in duties or privileges which would otherwise be open to them; legal disqualification,” ultimately conveying the social authority of disability. Each definition including more and more social processes that must be negotiated by both the disabled person and those around.

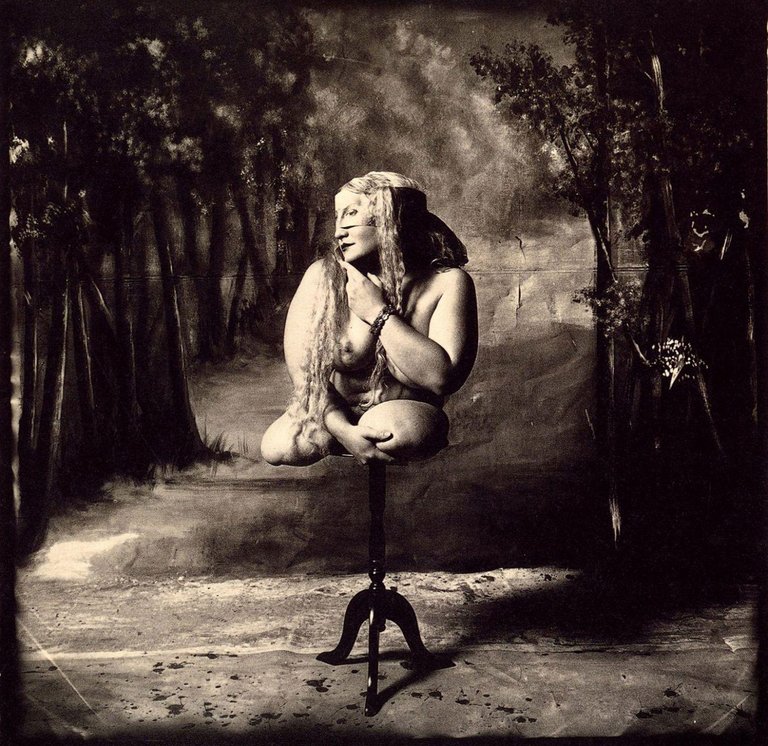

Joel-Peter Witkin "Woman on a Table" 1987

These definitions of the word disability begin by describing the effects said condition has, then considering the people who are personally unable to actively participate in undertakings requiring certain capabilities. Lastly, as the dictionary continues to give alternative, or more comprehensive, meanings, it integrates the constraints of what are socially determined restrictions on a person or class of persons, by the inclusion of legal designation, in the definition of disability. As Lennard J. Davis states in the Introduction of Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body, “disability, as we know the concept, is really a socially driven relation to the body that became relatively organized in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.” This final dictionary entry shows that disability is not just something an individual has to navigate. By highlighting the obligatory role the government plays, pertaining to the legal creation of the organization of social beliefs and attitudes about disability, definitional use of the word disability has led to a societally determined set of rules as to what disability is and what it is not. As Davis says, disability “is an absolute category without a level or threshold. One is either disabled or not. One cannon be a little disabled any more than one can be a little pregnant.” Using law to legitimize disability takes the necessary defining of disability away from the individual experiencing it and places the recognition and understanding of disability into the social realm of the observer. Looking at the photographs of Witkin, one must take both of these individual and social perceptions of disability into consideration.

Joel-Peter Witkin’s 1987 photograph, Woman on a Table, depicts a visibly disabled nude woman. She is the primary object of the photograph—floating center, perched on a small tea table, her head is turned slightly, with her hand on her face, coyly smiling. The backdrop is easily recognizable as such, with the wrinkles from being folded distinctly visible directly behind the model, the bottom end of the cloth clearly showing directly underneath her. She resembles a forest nymph, a solitary figure anticipating the fortuitousness of someone coming along, so that she may be appreciated. With or without admirers, she has the air of a lady who would be just as happy to be there, in that moment, with herself.

Witkin highlights the physical and medical existence of her disability, by positioning her on the pedestal, with the amputated ends of her appendages clearly showing. There is no question about the model’s medical physical disabilities. The audience cannot help but acknowledge her visible physical display of disability presented to them front and center. As Ann Millet-Gallant says in her essay, “Performing Amputation: The Photographs of Joel-Peter Witkin,” “Despite the plethora of visual detail, the viewer’s eyes are drawn to the sites of the model’s impairments.” One may attempt to look at other details of the photograph—the backdrop, the artist’s alterations to the photographic surface, the model’s mask or breasts—but, the viewer’s gaze somehow is always directed back to her physical manifestation of disability.

Witkin plays with the role society sees itself as having in her disability. He has placed her atop of a pedestal, in a pose which she could not have gotten into on her own. She is subject to be analyzed by the ever present viewer. Davis says, “A person with an impairment is turned into a disabled person by the Medusa-like gaze of the observer; paradoxically, the observer becomes disabled by his or her reaction to the disabled person.” Carefully placed, she is a prop for society to stare at, a thing to be described and labeled, something to manipulate as desired. Just by looking at her, those without incapacities are forced to confront their own place in this spectrum of disability.

In order to know whether Joel-Peter Witkin treats his models with respect, one must examine the words and actions of the models. If any of his images produced feelings of being exploited, in the models, one would expect the confirmation of such discomfort would be present in her body language. However, she looks content in her place, atop the pedestal. Again, she had to have had some sort of assistance to get herself into the pose and without her full comfort and cooperation, the image would betray any discomfort she felt. He has not done any retouching, or other photographic processing, to alter her image in an attempt to make her appear more like what society would deem “grotesque,” nor has he attempted to disguise her disability to turn her into what society would consider appealing. Though there is not an interview with this model, in Millet-Gallant’s essay Witkin is quoted as saying, of the model for another photograph (Humor and Fear), “the model responded to the finished photograph with pride, expressing that it made her feel beautiful.” One can hope that this model feels as attractive as she looks in this image; that she is pleased with the results.

Witkin use of these models with disabilities, especially those with bodily conditions that typically restrict them from being commonly considered for photography, causes any person to ask questions regarding the exploitation of these individuals. Do his representations of disability promote understanding of those who are in positions of limited ability? Perhaps. If anything, they allow people to analyze their own thoughts about the disabilities they have seen. Davis says, “Disability is not an object—a woman with a cane—but a social process that intimately involves everyone who has a body and lives in the world of the senses.” Hopefully, the viewer leaves with more questions and a motivation to do research of their own.

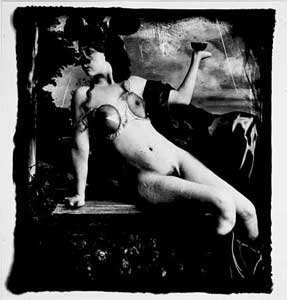

Joel-Peter Witkin "Humor and Fear"

Maybe, the need to question comes from a place within ourselves, as Ann Millet-Gallant has said, “Witkin’s work challenges cultural assumptions and judgements of bodies, what they do, and what should bring them pleasure. It forces us to confront our greatest fears, anxieties, and inhibitions about our own bodies, morality, and inevitable mortality.” As someone who has modeled for him more than just once herself and written about his work, the reader would expect her to disclose any feelings of exploitation or disrespect that she experienced. Instead, as a visibly disabled person, she seems to appreciate how his work makes others think about the humanity of disability, as well as how he comments on the sterilization of previous medical photographs of such, saying, “Witkin engages disabled bodies in dramas of myth, violence, monstrosity, and the supernatural, calling attention to their historical inclusion in such frames, yet simultaneously repeating some of the precarious subtexts that such legacies embody.” He has made the photographs a personal representation of the models, given them autonomy where they had previously been concealed and ambiguous.

Joel-Peter Witkin "First Casting for Milo" 2004

Joel-Peter Witkin’s photographs address a darker side of life—a side most of us try to ignore. Humans have the tendency to avoid anything that makes us uncomfortable and disability is one of those things that most abled people would like to pretend will never happen to them, especially a disability with a visible physical nature. Witkin’s portrayals of people with these type of bodies allows both the models and the audience a chance to address the disability personally. As Lennard Davis says, “The longer we live, the more likely we are to be disabled.” Witkin’s photographs allow us a fantasy glimpse into that world.

References:

Lennard J. Davis, “Disability: The Missing Term in the Race, Class, Gender Triad”

Ann Millett (Gallant), “Performing Amputation

Oxford English Dictionary

Beautiful explanation of photographs

Thank you. His work is amazing. I hope you go look at more :)

As always, a very good job.! Greetings!

Thank you! Really, Joel-Peter Witkin should have all the credit for this one :)

Resteemed to over 17900 followers and 100% upvoted. Thank you for using my service!

Send 0.200 Steem or 0.200 Steem Dollars and the URL in the memo to use the bot.

Read here how the bot from Berlin works.

We are happy to be part of the APPICS bounty program.

APPICS is a new social community based on Steem.

The presale was sold in 26 minutes. The ICO is open now for 4 rounds in 4 weeks.

Read here more: https://steemit.com/steemit/@resteem.bot/what-is-appics

@resteem.bot

I am new here! And happy to read your post. The work of Joel-Peter Witkin is inspiring, it makes trouble and makes me reflect on beauty norms. I met the artists/activists of "Yes We Fuck" (Antonio Centeno, Raúl de la Morena, Post-Op) who engage with the notion of "diversidad functional" (as an empowering language tactic to counter-define the notion of "disability").