Building upon the previous piece, Rethinking Artificial Intelligence, I begin by connecting the historical myths involving artificial intelligence to the social and political upheaval of the Industrial Revolutions.

The full essay, "Will Robots Want to Vote? An Investigation into the Implications of Artificial Intelligence for Liberty and Democracy," was written as part of a fellowship for The Fund for American Studies Robert Novak Journalism Program. For an introduction to the premise of the project, please read my speech, Will Robots Want to Vote? For an introductory summary to the final essay, please read, This will begin to make things right. The project is presented as a multi-part series. This is Part 2.

If you liked this post, please consider sharing, commenting, and upvoting. Thank you in advance. - Josh

What is artificial intelligence?

The term artificial intelligence gets thrown around quite a bit these days, conjuring imagery ranging from killer sex robots that will be responsible for civilization-altering unemployment, to Google and Amazon-powered smart homes and self-driving Teslas that respond to and solve the inconveniences of modern life.

At its core, artificial intelligence is machine intelligence. But this is where the distinction becomes more philosophical than technical because we then need to ask what it is that makes something “intelligent." The notion of what it means for a machine to be artificially intelligent is broad and ever-evolving.

The word robot was first introduced into the English language nearly a century ago by playwright Karel Čapek from the Czech word for “slave,” for example, but the idea of automatons that mimic human behavior goes back to Antiquity.

In Greek mythology, Hephaestus, the disabled blacksmith of Mount Olympus, built robots to help himself move around. The Liezi, an ancient Chinese text from the 3rd century B.C., tells the tale of a mechanical man created for the king by an engineer named Yan Shi. The story of thinking machines is an old one.

What should we make of the impact of the current state of A.I. research and development? In a July 2016 speech, Jason Furman, former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under former President Barack Obama, said that “to date, AI has not had a large impact on the aggregate performance of the macroeconomy or the labor market.”

“But it will likely become more important in the years to come, bringing substantial opportunities - and our first impulse should be to embrace it fully,” said Furman.

On the other hand, author and game designer Ian Bogost, writing in a recent piece in The Atlantic, echoed the argument of other prominent AI researchers that the ubiquity of “artificial intelligence” in modern technology has essentially rendered the term “meaningless.”

“What to make, then, of the explosion of supposed-AI in media, industry, and technology?” asks Bogost.

“In some cases, the AI designation might be warranted, even if with some aspiration. Autonomous vehicles, for example, don’t quite measure up to R2D2 (or Hal), but they do deploy a combination of sensors, data, and computation to perform the complex work of driving,” said Bogost. “But in most cases, the systems making claims to artificial intelligence aren’t sentient, self-aware, volitional, or even surprising. They’re just software.”

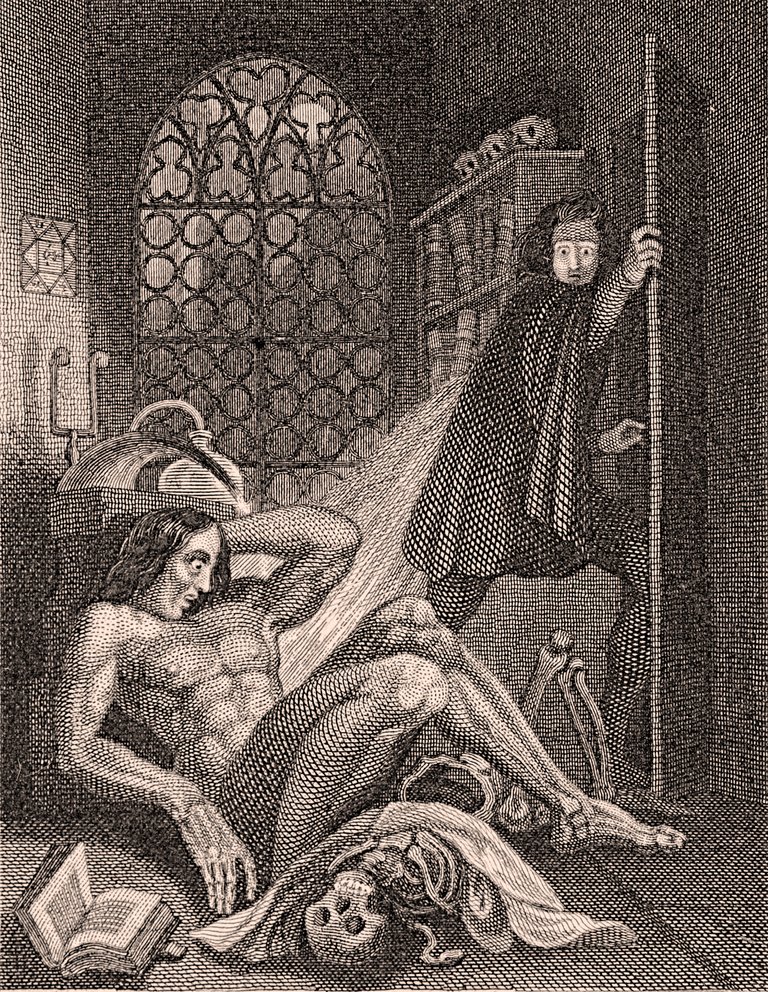

Frankenstein’s monster

Yet, darker narratives surrounding humanity’s creations coming to life have their origins well before our current clickbait news era.

Published in 1818 at during the latter half of the first Industrial Revolution in Europe, Mary Shelly's novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, for example, tells the tale of an adversarial relationship between a monster and his creator, Dr. Victor Frankenstein.

Not only do the darker stories serve as a warning of the future possibility of our machines turning on us if we are not careful, they also serve to illuminate our relationship with our creations over time, particularly the past several hundred years.

As we approach futurist Ray Kurzweil’s so-called technological singularity, a mythical date somewhere around the year 2045 when computers will surpass human intelligence, technological anxiety appears to only be increasing. Elon Musk, Tesla’s founder and CEO, is famous for his worry over killer AI.

But as The Economist noted in a 2016 article on the ethical considerations of artificial intelligence, the debate over whether or not we run the risk of the technology going rogue is far from settled. Dr. Demis Hassabis, founder and CEO of the Google-owned A.I. research firm, DeepMind, for example, says A.I. alarmism is inspired by science fiction and promulgated by people who are not working very closely with the technology.

The notion persists as a reliable trope in popular culture, however, suggesting its roots run deep. After all, the killer robot science fiction genre — with characters ranging from Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Skynet and the terminators in the Terminator franchise, to Ava in Ex Machina, — is really just a contemporary rehashing of Frankenstein.

Norma Rowen, a now-retired humanities professor at Toronto's York University, wrote in a 1992 essay that Shelly herself recognized that "in spite of his new techniques, Victor Frankenstein is part of an old tradition."

Frankenstein, Shelly wrote, was inspired to create life based on the earlier attempts of Albertus Magnus, a 13th-century German Dominican friar, Cornelius Agrippa, a Renaissance-era German mystic, and Paracelsus, a Renaissance-era alchemist.

Revolutions

While Frankenstein serves as the inspiration for our modern nightmares, Shelly drew inspiration from the upheaval of her own era.

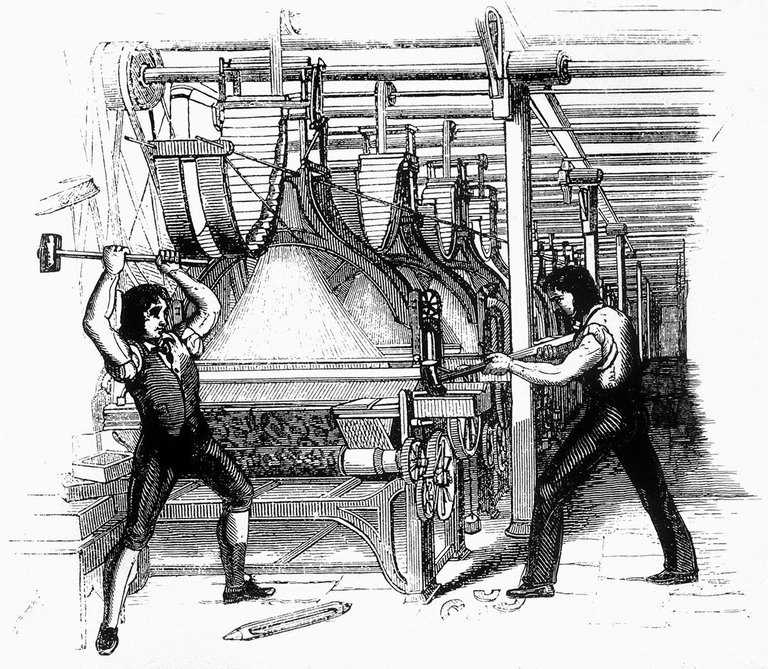

In a 1994 essay for the Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, "Revolutionary Readings: Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and the Luddite Uprisings," author Edith Anne Gardner wrote that Frankenstein is an allegory of the Luddite uprisings in early 19th century Britain.

Great Britain was the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution in the later years of the previous century. The Luddites were a group of British professional textile workers who destroyed machines in protest against what they perceived to be manufacturers’ unfair labor practices.

Depending on who you ask, the Industrial Revolution, to borrow Charles Dickens’ description of the concurrent French Revolution in his novel A Tale of Two Cities, “the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

Capitalism’s critics point to the era as a prime example of worker exploitation and massive wealth inequality, while it’s its defenders argue that workers saw rises in wages and living conditions.

One reason, as a 2013 blog post by The Economist suggests, is that little academic consensus exists regarding an increase in real wages for British commoners from 1780-1840, and the health of commoners around that time was also a bit of a mixed bag.

Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum declared in a January 2016 report that we are currently “on the brink” of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

"The First Industrial Revolution used water and steam power to mechanize production. The Second used electric power to create mass production. The Third used electronics and information technology to automate production," said Schwab.

"Now a Fourth Industrial Revolution is building on the Third, the digital revolution that has been occurring since the middle of the last century. It is characterized by a fusion of technologies that is blurring the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres," said Schwab.

Writing for Future Tense, Elizabeth Garbee responded to Schwab’s claim, stating that the term “fourth Fourth Industrial Revolution” is far from new – it goes back to the 1940s. But to understand our current age and the potential impact artificial intelligence could have on liberty and democracy, we’ll need to better understand the preceding Industrial Revolutions.

Thank you for reading,

- Josh

Further Reading

- "Reskilling policies a productivity must in Industry 4.0 era, says APO Secretary-General." Marketwired. October 24, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/reskilling-policies-productivity-must-industry-080846458.html.

- Gaunt, Jeremy. "Red October: Russia of 1917 and 2017 closer than might be expected." Reuters. https://www.yahoo.com/news/red-october-russia-1917-2017-closer-might-expected-120347811.html.

- Ghoshal, Abhimanyu. "Facebook’s AI creating its own language is nothing to be afraid of." The Next Web. August 2, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://thenextweb.com/artificial-intelligence/2017/08/02/facebooks-ai-creating-its-own-language-is-nothing-to-be-afraid-of/.

- Lescaze, Zoe. "The Pop-Culture Evolution of Frankenstein’s Monster." The New York Times. October 23, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/23/books/review/christopher-frayling-frankenstein.html.

- Levy, Steven. "Algorithms Have Already Gone Rogue." Backchannel. October 4, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://www.wired.com/story/tim-oreilly-algorithms-have-already-gone-rogue/.

- Roose, Kevin. "Facebook’s Frankenstein Moment." The New York Times. September 21, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/21/technology/facebook-frankenstein-sandberg-ads.html.

- Severn, David. "The Society Left Behind by the Death of Britain's Mining Industry." VICE. October 18, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/evvm4z/touching-photos-from-britains-former-coalfields-v24n7.

- Stern, Ken. "Former NPR CEO opens up about liberal media bias." New York Post. October 21, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://nypost.com/2017/10/21/the-other-half-of-america-that-the-liberal-media-doesnt-cover/.

- Venkataraman, Bina. "The Problem With “Playing God”." Future Tense. January 11, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2017/01/frankenstein_and_the_problem_with_playing_god.html.

- Waters, Richard. "Frankenstein fears hang over AI." Financial Times. February 15, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/8e228692-f251-11e6-8758-6876151821a6.

- Zito, Salena. "The day that destroyed the working class and sowed the seeds of Trump." New York Post. September 16, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://nypost.com/2017/09/16/the-day-that-destroyed-the-working-class-and-sowed-the-seeds-for-trump/.

Related Posts by Josh Peterson

- "Rethinking Artificial Intelligence." Steemit. October 22, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://steemit.com/artificial-intelligence/@joshpeterson/rethinking-artificial-intelligence

- "This will begin to make things right." Steemit. October 22, 2017. Accessed October 22, 2017. https://steemit.com/writing/@joshpeterson/this-will-begin-to-make-things-right.

- "Will Robots Want to Vote?" Steemit. October 19, 2017. Accessed October 22, 2017. https://steemit.com/artificial-intelligence/@joshpeterson/will-robots-want-to-vote.

View Post History

This is fascinating.

Thank you, my friend.

@originalworks

To call @OriginalWorks, simply reply to any post with @originalworks or !originalworks in your message!