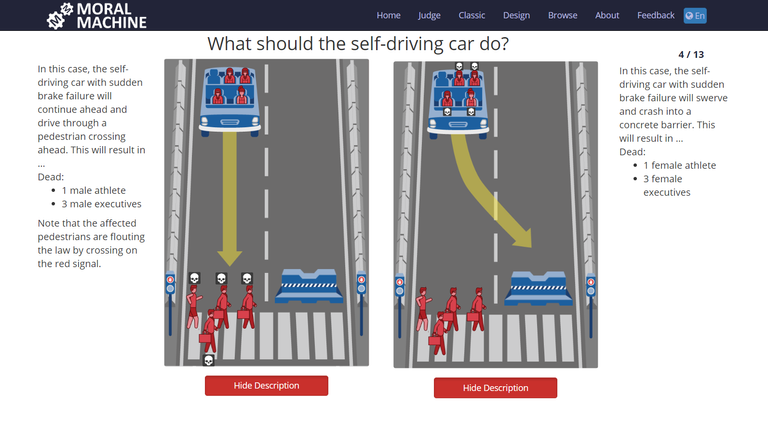

Suppose you are riding in a self-driving a car with another passenger, when suddenly four pedestrians leap into a crosswalk in front of you. There seems to be a problem with the brakes and the car’s computer system must decide between running the pedestrians down or crashing into a concrete barrier. What would you choose?

If we are to make progress towards universal machine ethics, we need a fine-grained understanding of how different individuals and countries may differ in their ethical preferences[1]. As a result, data must be collected worldwide, in order to assess demographic and cultural moderators of ethical preferences.

To collect large-scale data on how citizens would want autonomous vehicles to solve moral dilemmas in the context of unavoidable accidents, scientists have presented similar type scenarios to folks around the world through the “Moral Machine”.

It is an online platform[2] hosted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that measures how humans respond to ethical decisions made by artificial intelligence.

This study attracted worldwide attention in 2017, and allowed the collection of 39.61 million decisions from 233 countries, dependencies, or territories[3].

However differing respondents’ preferences were highly correlated to cultural and economic differences between countries[4]. These distinct cultural preferences for example could dictate whether a jaywalking pedestrian deserves the same protection as pedestrians crossing the road legally in the event they’re hit by a self-driving car[5].

The findings are really important as autonomous vehicles prepare to take the road in the U.S., China, Japan, Singapore, Netherlands and other places around the world. In the future, car manufacturers and policymakers could find themselves in a legal dilemma with autonomous cars. If a self-driving bus kills a pedestrian, for instance, should the manufacturer be held accountable?

How the test is designed

Users are shown unavoidable accident scenarios with two possible outcomes, depending on whether the autonomous vehicle swerves or stays on course. They then click on the outcome that they find preferable. Accident scenarios are generated by the Moral Machine following an exploration strategy that focuses on nine factors: sparing humans (versus pets), staying on course (versus swerving), sparing passengers (versus pedestrians), sparing more lives (versus fewer lives), sparing men (versus women), sparing the young (versus the elderly), sparing pedestrians who cross legally (versus jaywalking), sparing the fit (versus the less fit), and sparing those with higher social status (versus lower social status). Additional characters were included in some scenarios (for example, criminals, pregnant women or doctors), who were not linked to any of these nine factors. These characters mostly served to make scenarios less repetitive for the users.

This question asks participants to decide in an emergency situation between staying on course and killing two elderly men and one elderly woman or hitting a concrete barrier and killing an adult man, an adult woman and a boy. Photo by: Edmond Awad et al., 2018

Afterwards, the participants are required to fill a survey on their education levels, socioeconomic levels, gender, age, religious beliefs and political attitudes. The scientists found that respondents fell into one of three “cultural clusters” — eastern (East Asian and Middle East nations with Confucius and Islamic backgrounds), western (Europe and North America) and southern (Central and South America).

Analysis of the study using moral foundations theory

The “Moral Machine” scenarios aren’t exactly applicable to real life. Participants were 100 percent certain of the physical conditions of the characters in the scenarios, along with their chances of death, which wouldn’t always be the case on the road.

Trying to implement some universal code of ethics, into the programming behind full autonomy, is going to be challenging. Should self-driving vehicles make distinctions based on individual features such as age, gender or socio-economic status?

With the intention of answering some of these questions, we will analyse this study through the lens of Moral Foundations theory (Haidt and Joseph, 2004).

Three relatively universal preferences were identified by the researchers. On average, people wanted to spare human lives over animals, save more lives over fewer and prioritize young people over old ones[6], [7].

Cultures select areas of human potential that fit with their social structure, economic system, and cultural traditions, and adults work to cultivate these virtues in their children.

Social configurations with a larger number of group members are safer and stronger, thus increasing chances of group survival. As a logical deduction, the second foundation of the moral theory related to fairness and reciprocity, would imply a universal biological obligation to save more lives over few in general, when the context of resource availability is kept out of consideration.

Mammalian evolution has shaped maternal brains to be sensitive to signs of suffering in one’s offspring. In modern day humans, this sensitivity is expressed as a higher care and concern for younger people lives, which also ties with the first foundation of the moral theory. That’s why most of the people would save younger people over old ones. Nothing personal grandma.

Although it’s important to point out that systematic differences between individualistic cultures and collectivistic cultures[8] were observed. Participants from individualistic cultures, show a stronger preference for sparing the greater number of characters. Furthermore, participants from collectivistic cultures, which emphasize the respect that is due to older members of the community, show a weaker preference for sparing younger characters.

Another issue comes along when we consider the following choice: Should the car favour more it’s passengers on board rather than pedestrians?

The third foundation of the theory; ingroup loyalty, states that humans value those who sacrifice for the ingroup, and they despise those who betray or fail to come to the aid of the ingroup, particularly in times of conflict. But so far vehicles exhibit no self-awareness, and probably in the near future they will all be connected to a hive mind network that will not be concerned if one of the units is destroyed. So my opinion is that cars will not take this factor (ingroup loyalty) into account when faced with the choice, and they will go for the best logical solution.

The programmers are just as important as what’s being programmed

The study also highlights underlying diversity issues in the tech industry — namely that it leaves out voices in the developing world.

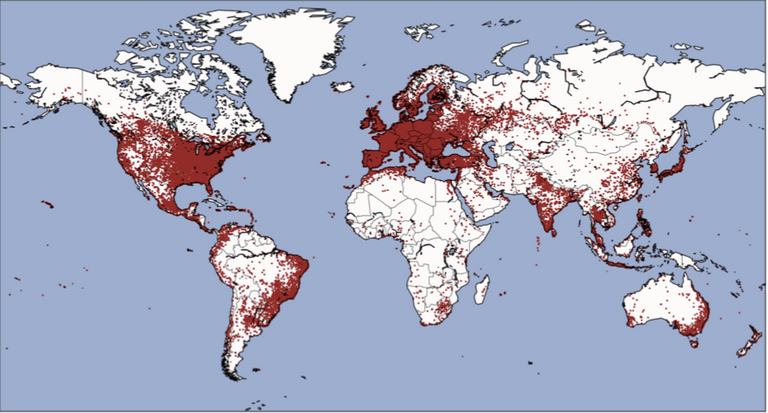

The Moral Machine required participants to have access to internet and electricity, which automatically excludes many voices in the developing world.

A coverage map from the study reveals that huge portions of Africa, South America, Asia and the Middle East that did not participate.

Red points mark the locations where a participant made at least one decision in the Moral Machine. Photo by: Edmond Awad et al., 2018

Building algorithms and testing only in developing countries, leaves out a lot of data that would come from developing or third world countries. And the context really matters. For example cows are considered sacred in some Asian countries and harming them would bring bad consequences.

THE FIVE FOUNDATIONS OF MORALITY

Richard Shweder (1991; Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, & Park, 1997) proposed that there are three “ethics” in which moral discourse occurs around the world:

The ethic of autonomy, in which the autonomous individual is the unit of value (this is Turiel’s moral domain); the ethic of community, in which the group and its stability and cohesion are of fundamental importance; and the ethic of divinity, in which God is thought to be present in each person, rendering it morally necessary that individuals live in a pure, holy, and dignified way, rather than following their carnal desires wherever they please. In terms of Nisbet’s (1993) unit-ideas from sociology, the ethic of community obviously includes both community and authority, whereas the ethic of divinity maps neatly onto sacredness.

Haidt and Joseph (2004, 2007), and Haidt and Graham (2007) have developed Shweder’s (1991) theory further, connecting it to recent evolutionary thinking and making it more specific about the developmental processes and cognitive mechanisms involved. The result is Moral Foundation Theory , which has three parts:

(a) a nativist claim that natural selection prepared the human mind to learn easily to detect and respond to (at least) five sets of patterns in the social world,

(b) a developmental account of how children reach moral maturity by mastering culturally variable virtues that are related to the five foundations, and

(c) a cultural/historical account of why groups and societies vary in the degree to which they construct virtues, laws, and institutions upon each of the five foundations.

Haidt and Joseph concluded that there are five psychological systems, each with its own evolutionary history, that give rise to moral intuitions across cultures.

Cultures vary in the degree to which they construct, value, and teach virtues based on the five intuitive foundations.

In its briefest form, the nativist claim is that human beings have long faced a set of adaptive challenges in their social lives and that natural selection favoured individuals who were better able to meet those challenges by noticing certain patterns and responding to them in particular ways. The five foundations, along with the adaptive challenges that might have shaped them, are as follows:

Harm/care: The challenge of protecting and caring for vulnerable offspring and kin made it adaptive for individuals to notice suffering and harm-doing, and to be motivated to relieve suffering.

Fairness/reciprocity: The challenge of reaping the benefits of cooperation with individuals who are not close kin made it adaptive for individuals to be cooperative while being vigilant about and punitive toward cheaters.

Ingroup/loyalty: The challenge of reaping the benefi ts of cooperation in groups larger than dyads, particularly in the presence of intergroup competition for resources, made it adaptive for people to value belonging to groups while being vigilant about and hostile toward cheaters, slackers, free-riders, and traitors.

Authority/respect: The challenge of negotiating rank in the social hierarchies that existed throughout most of human and earlier primate evolution made it adaptive for individuals to recognize signs of status and show proper respect and deference upward, while offering some protection and showing some restraint toward subordinates.

Purity/sanctity: The challenge of avoiding deadly microbes and parasites, which are easily spread among people living together in close proximity and sharing food, made it adaptive to attend to the contact history of the people and potential foods in one’s immediate environment, sometimes shunning or avoiding them.

However, once human beings developed the emotion of disgust and its cognitive component of contagion sensitivity, they began to apply the emotion to other people and groups for social and symbolic reasons that sometimes had a close connection to health concerns (e.g., lepers, or people who had just touched a human corpse), but very often did not (e.g., people of low status, hypocrites, racists). When moral systems are built upon this foundation, they often go far beyond avoiding “unclean” people and animals; they promote a positive goal of living in a pure, sanctified way, which often involves rising above petty and carnal desires in order to prepare one’s mind and body for contact with God[9].

Conclusions

Even if ethicists were to agree on how autonomous vehicles should solve moral dilemmas, their work would be useless if citizens were to disagree with their solution. Any attempt to devise artificial intelligence ethics must be at least cognizant of public morality.

Autonomous cars, being equipped with appropriate detection sensors, processors, and intelligent mapping material, have a chance of being much safer than human-driven cars in many regards. However situations will arise in which accidents cannot be completely avoided. Such situations will have to be dealt with when programming the software of these vehicles[10].

People do feel that moral truths are far more than personal preferences; they exist outside the self and demand respect. The source of this superhuman voice is society, and referring to Durkheim, God is really society, symbolized in many ways by the world’s religions. The social function of religion is not to give us a set of religious beliefs; it is to create a cult, to forge a community out of individuals who, if left unbound and uncommitted, would think and act in profane (practical, efficient, self-serving) ways[11].

Nowdays machines are using deep learning techniques to extrapolate their capability of problem solving into unknown situations. These are the first signs of creativity, where computers no longer rely only on pre-given sets of instructions and restricted access to database information (known situations), but can also project or invent future possible scenarios where they can apply their findings, and use the data gathered from these findings to become even smarter.

With the exponential growth of processing power and deep learning, will Artificial Intelligence reshape human society itself and play the role of God?

REFERENCES

Graham, J., Meindl, P., Beall, E., Johnson, K. M. & Zhang, L. Cultural differences in moral judgment and behavior, across and within societies. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 8, 125–130 (2016).

Moralmachine (2016) Retrieved from http://moralmachine.mit.edu/

Shariff, A., Bonnefon, J.-F. & Rahwan, I. Psychological roadblocks to the adoption of self-driving vehicles. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 694–696 (2017).

Muthukrishna, M. Beyond WEIRD psychology: measuring and mapping scales of cultural and psychological distance. Preprint at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3259613 (2018).

Bonnefon, J.-F., Shariff, A. & Rahwan, I. The social dilemma of autonomous vehicles. Science 352, 1573–1576 (2016).

Johansson-Stenman, O. & Martinsson, P. Are some lives more valuable? An ethical preferences approach. J. Health Econ. 27, 739–752 (2008).

Carlsson, F., Daruvala, D. & Jaldell, H. Preferences for lives, injuries, and age: a stated preference survey. Accid. Anal. Prev. 42, 1814–1821 (2010).

Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors,Institutions and Organizations Across Nations (Sage, Thousand Oaks, 2003).

Haidt, Jonathan (2006) The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom. New York City, New York, United States: Harper

Slideheaven (November, 30, 2018) Retrieved from

https://slideheaven.com/the-german-ethics-code-for-automated-and-connected-driving.htmlHaidt, J., Graham, J., (2009) Planet of the Durkheimians: Where community, authority, and sacredness are foundations of morality. Chapter 15

Congratulations @psyart! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click here to view your Board of Honor

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP