Bangladesh is a country. Part-6.

The Society and Its Environment.

BANGLADESH IS NOTED for the astounding ethnic and social homogeneity of its populace. More than 98 percent of its kin are Bengalis; the rest of Biharis, or non-Bengali Muslims, and indigenous inborn people groups. Bangladeshis are especially pleased with their rich social and semantic legacy on the grounds that their autonomous country is in part the aftereffect of a great development to maintain and safeguard their dialect and culture. Bangladeshis recognize themselves intimately with Bangla, their national dialect.

One of the world's most thickly populated countries, Bangladesh in the 1980s was gotten in the endless loop of populace development and destitution. Despite the fact that the rate of development had declined possibly as of late, the quick extension of the populace kept on being a gigantic weight on the country. With 82 percent of its kin living in the wide open, Bangladesh was likewise a standout amongst the most provincial countries in the Third World. The pace of urbanization in the late 1980s was moderate, and urban zones needed satisfactory civilities and administrations to assimilate even those vagrants who trekked from country territories to the urban places for sustenance and work. Visit cataclysmic events, for example, beach front typhoons and surges, executed thousands, and boundless lack of healthy sustenance and poor sanitation brought about high death rates from an assortment of ailments.

In the late 1980s, destitution remained the most remarkable part of Bangladeshi society. In spite of the fact that the divergence in wage between various portions of the general public was not awesome, the frequency of destitution was far reaching; the extent of the populace in extraordinary neediness—those unfit to manage the cost of sufficiently even sustenance to carry on with a sensibly dynamic life—ascended from 43 percent in 1974 to 50 percent in the mid-1980s. The developing political tip top, which constituted an exceptionally restricted social class contrasted and the mass of laborers and urban poor, held the way to political power, controlled all organizations, and delighted in the best financial additions. Urban in habitation, conversant in English, and alright with Western culture, they were seen by numerous onlookers as socially and socially distanced from the majority. Toward the finish of the 1980s, Bangladeshi society kept on being experiencing significant change—from the beginning of autonomy as well as from the frontier and Pakistani periods too—as new qualities continuously supplanted customary ones.

About 83 percent Muslim, Bangladesh positioned third in Islamic populace around the world, after Indonesia and Pakistan. Sunni Islam was the overwhelming religion among Bangladeshis. Despite the fact that faithfulness to Islam was profoundly established, by and large convictions and observances in rustic territories tended to strife with universal Islam.

Be that as it may, the nation was amazingly free of partisan struggle. For most adherents Islam was to a great extent a matter of standard practice and mores. In the late twentieth century fundamentalists were demonstrating some hierarchical quality, however in the late 1980s their numbers and impact were accepted to be constrained. Proclaimed in June 1988, the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution perceives Islam as the state religion, however the full ramifications of this measure were not obvious in the months following its selection. Hindus constituted the biggest religious minority at 16 percent; different minorities included Buddhists and Christians.

Since its introduction to the world in 1971, Bangladesh has endured both normal cataclysms and political changes. In July—September 1987, for instance, the nation encountered its most exceedingly bad surges in over thirty years, and surges amid a similar period in 1988 were much all the more annihilating. In 1987 more than US$250 million of the monetary framework was devastated, the fundamental rice edit was extremely harmed, and an expected 1,800 lives were lost. The 1988 surges secured more than 66% of the nation, and in excess of 2,100 passed on from flooding and resulting ailment. The nation likewise experienced a time of political agitation instigated by real restriction political gatherings. Persevering vulnerabilities as the 1990s drew nearer will undoubtedly affect social advancement, particularly in the regions of training, improvement of the work power, sustenance, and the working of foundation for satisfactory human services and populace control.

Geography.

The Land-

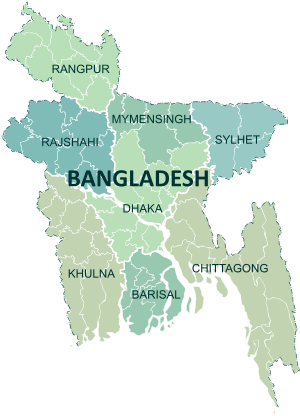

The physiography of Bangladesh is described by two unmistakable highlights: an expansive deltaic plain subject to visit flooding, and a little uneven district crossed by quickly streaming waterways. The nation has a region of 144,000 square kilometers and stretches out 820 kilometers north to south and 600 kilometers east to west. Bangladesh is verged on the west, north, and east by a 2,400-kilometer arrive outskirts with India and, in the southeast, by a short land and water wilderness (193 kilometers) with Burma. On the south is an exceedingly unpredictable deltaic coastline of around 600 kilometers, fissured by numerous waterways and streams streaming into the Bay of Bengal. The regional waters of Bangladesh broaden 12 nautical miles, and the selective monetary zone of the nation is 200 nautical miles.

Approximately 80 percent of the landmass is comprised of rich alluvial swamp called the Bangladesh Plain. The plain is a piece of the bigger Plain of Bengal, which is now and then called the Lower Gangetic Plain. In spite of the fact that heights up to 105 meters above ocean level happen in the northern piece of the plain, most rises are under 10 meters above ocean level; rises diminish in the beach front south, where the territory is for the most part adrift level. With such low heights and various streams, water—and associative flooding—is a dominating physical component. Around 10,000 square kilometers of the aggregate zone of Bangladesh is secured with water, and bigger territories are routinely overflowed amid the storm season (see Climate; River Systems, this ch.).

The main exemptions to Bangladesh's low heights are the Chittagong Hills in the southeast, the Low Hills of Sylhet in the upper east, and good countries in the north and northwest (see fig. 5). The Chittagong Hills constitute the main critical slope framework in the nation and, in actuality, are the western edge of the north-south mountain scopes of Burma and eastern India. The Chittagong Hills rise steeply to limit edge lines, by and large no more extensive than 36 meters, 600 to 900 meters above ocean level. At 1,046 meters, the most astounding rise in Bangladesh is found at Keokradong, in the southeastern piece of the slopes. Prolific valleys lie between the slope lines, which by and large run north-south. West of the Chittagong Hills is an expansive plain, cut by waterways depleting into the Bay of Bengal, that ascents to a last chain of low beach front slopes, for the most part beneath 200 meters, that accomplish a greatest rise of 350 meters. West of these slopes is a restricted, wet waterfront plain situated between the urban communities of Chittagong in the north and Cox's Bazar in the south.

Around 67 percent of Bangladesh's nonurban arrive is arable. Perpetual products cover just 2 percent, glades and fields cover 4 percent, and timberlands and forest cover around 16 percent. The nation delivers expansive amounts of value timber, bamboo, and sugarcane. Bamboo develops in all zones, however top notch timber develops for the most part in the good country valleys. Elastic planting in the sloping locales of the nation was attempted in the 1980s, and elastic extraction had begun before the decade's over. An assortment of wild creatures are found in the backwoods regions, for example, in the Sundarbans on the southwest drift, which is the home of the world-acclaimed Royal Bengal Tiger. The alluvial soils in the Bangladesh Plain are by and large ripe and are improved with substantial sediment stores conveyed downstream amid the blustery season.

Climate.

Bangladesh has a subtropical storm atmosphere described by wide regular varieties in precipitation, modestly warm temperatures, and high stickiness. Provincial climatic contrasts in this level nation are minor. Three seasons are by and large perceived: a sweltering, moist summer from March to June; a cool, stormy rainstorm season from June to October; and a cool, dry winter from October to March. When all is said in done, greatest summer temperatures go in the vicinity of 32°C and 38°C. April is the hottest month in many parts of the nation. January is the coldest month, when the normal temperature for a large portion of the nation is 10°C.

Winds are for the most part from the north and northwest in the winter, blowing delicately at one to three kilometers for each hour in northern and focal zones and three to six kilometers for every hour close to the drift. From March to May, savage rainstorms, called northwesters by nearby English speakers, create winds of up to sixty kilometers for every hour. Amid the exceptional tempests of the late-spring and late storm season, southerly breezes of in excess of 160 kilometers for each hour make waves peak as high as 6 meters in the Bay of Bengal, which brings shocking flooding to beach front zones.

Overwhelming precipitation is normal for Bangladesh. Except for the moderately dry western area of Rajshahi, where the yearly precipitation is around 160 centimeters, most parts of the nation get no less than 200 centimeters of precipitation for every year (see fig. 1). On account of its area only south of the lower regions of the Himalayas, where rainstorm winds turn west and northwest, the district of Sylhet in northeastern Bangladesh gets the best normal precipitation. From 1977 to 1986, yearly precipitation in that area extended in the vicinity of 328 and 478 centimeters for each year. Normal every day dampness ran from March lows of in the vicinity of 45 and 71 percent to July highs of in the vicinity of 84 and 92 percent, in view of readings taken at chosen stations across the nation in 1986 (see fig. 3; table 2, Appendix).

Around 80 percent of Bangladesh's rain falls amid the rainstorm season. The rainstorm result from the complexities amongst low and high pneumatic force regions that outcome from differential warming of land and water. Amid the hot long periods of April and May hot air ascends over the Indian subcontinent, making low-weight territories into which surge cooler, dampness bearing breezes from the Indian Ocean. This is the southwest storm, beginning in June and typically enduring through September. Partitioning against the Indian landmass, the rainstorm streams in two branches, one of which strikes western India. Alternate goes up the Bay of Bengal and over eastern India and Bangladesh, crossing the plain toward the north and upper east before being swung toward the west and northwest by the lower regions of the Himalayas (see fig. 4).

Regular catastrophes, for example, surges, tropical twisters, tornadoes, and tidal bores—ruinous waves or surges caused by surge tides hurrying up estuaries—assault the nation, especially the seaside belt, relatively consistently. In the vicinity of 1947 and 1988, thirteen extreme tornados hit Bangladesh, causing tremendous death toll and property. In May 1985, for instance, a serious cyclonic tempest pressing 154 kilometer-per-hour winds and waves 4 meters high cleared into southeastern and southern Bangladesh, killing in excess of 11,000 people, harming in excess of 94,000 houses, killing somewhere in the range of 135,000 head of domesticated animals, and harming almost 400 kilometers of fundamentally required banks. Yearly storm flooding brings about the loss of human life, harm to property and correspondence frameworks, and a deficiency of drinking water, which prompts the spread of sickness. For instance, in 1988 66% of Bangladesh's sixty-four areas experienced broad surge harm in the wake of bizarrely overwhelming downpours that overflowed the waterway frameworks. Millions were left destitute and without consumable water. Half of Dhaka, including the runways at the Zia International Airport—a vital travel point for calamity help supplies—was overwhelmed. Around 2 million tons of yields were accounted for crushed, and alleviation work was rendered significantly more difficult than expected in light of the fact that the surge made transportation of any sort exceedingly troublesome.

There are no safeguards against twisters and tidal bores with the exception of giving preemptive guidance and giving safe open structures where individuals may take protect. Sufficient framework and air transport offices that would facilitate the sufferings of the influenced individuals had not been set up by the late 1980s. Endeavors by the administration under the Third Five-Year Plan (1985—90) were coordinated toward precise and opportune figure capacity through agrometeorology, marine meteorology, oceanography, hydrometeorology, and seismology. Fundamental master administrations, hardware, and preparing offices were relied upon to be created under the United Nations Development Program (see Foreign Assistance, ch. 3).

nice one

Posted using Partiko Android

tnq

your post is very beautiful

Tnx for support

Arrengment of post is nice

thank you

বাংলাদেশের আবহাওয়া অনেক সুন্দর। প্রকৃতি এবং এর সুন্দর্য দেখে আমি মুগ্ধ।

Yup bangladesh weather is so amazing

Very informative post to know about Bangladesh.

God to let you know that