In my youthful years, when summer vacations stretched out in a glorious parade of days, baseball was a daily sacrament.

A typical summer day, circa 1991, consisted of a series of regimented activities, all structured around our now erstwhile American pastime. While there was daylight, there was baseball to be played. The usual itinerary of my neighborhood pals and I consisted of: breakfast, baseball, lunch, baseball, dinner, baseball. After sunset, a dip in the pool was usually followed by a baseball game on TV. If there wasn’t a televised game that day—as occasionally happened during ESPN’s insufferable “Knockdown Thursdays,” when baseball was supplanted by boxing and bowling—the Nintendo video game RBI Baseball 2, which featured the 1989 MLB rosters, was a decent alternative.

On rainy days, video games were the only antidote to baseball withdrawal. Besides RBI 2, there was the DOS computer classic Earl Weaver Baseball, released in 1987. The graphics were rudimentary, and the computer-controlled performance of the fielders and runners was often infuriatingly fickle, but the premise of the game was brilliant.

Earl Weaver Baseball, named after the irascible fireplug who managed the Baltimore Orioles for 17 seasons and swore by the Holy Trinity of “pitching, defense, and the three-run homer,” let users select decadal all-star teams in the American or National leagues from the 1920s through the 1970s. The age-old question of whether the hefty 1927 bat of Babe Ruth could handle the intimidating 1968 fastball of Bob Gibson was thus settled in infinite permutations through keystrokes and a little luck.

The game, which allowed users to create customized teams comprised of players from any era, precipitated the nostalgia craze that followed the late ’80s release of the baseball-movie classics “Eight Men Out” and “Field of Dreams,” both of which featured disgraced Chicago White Sox outfielder “Shoeless” Joe Jackson as their mythical centerpieces.

The ultimate “Field of Dreams” team—the nine men (or 10, if you include a designated hitter), living or dead, you’d want to see walk out of a cornfield for a Sunday afternoon doubleheader in heaven—is a topic I’ve been mulling over since those childhood summers spent creating virtual Earl Weaver all-star squads.

To be clear, the following is not an attempt to assemble a team of the all-time greatest players at each position. The absence of names like Ruth, Mays and Wagner should be a clear indication that my empyrean roster has a personal bias.

The criteria I set for my team are based on two simple principles:

• The player must either be in the Hall of Fame or have established a precedent of HOF-worthy statistics.

• He must also be a nice guy.

I’ve established an age for each player on the squad, based on the best year of his respective career. In some instances, the player’s career year was easy to single out. In other cases it was more difficult—such as Hank Aaron, whose career was consistently great but which lacked one clear standout season. I’ve also included one active player, who at age 25 has probably yet to deliver his best season.

So, here’s my lineup card for that summer day in this life or the next when lazy cumulus clouds float in an unbelievably blue sky and leather meets ash in perfect harmony:

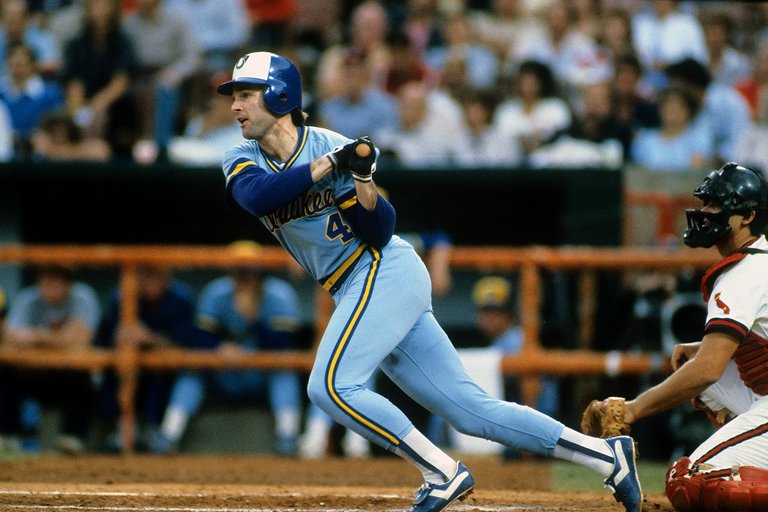

1.) Paul Molitor, DH (Milwaukee Brewers, 1987)

Molitor's best season might be 1993, when he was a full-time designated hitter and batted .332 with 22 home runs, 111 RBIs, 22 stolen bases and a league-leading 211 hits, en route to a second-place finish in the American League MVP voting as a member of the World Champion Toronto Blue Jays. But I want the 1987 Molitor leading off, back when he earned his nickname “The Ignitor” as the Brewers leadoff hitter during a 39-game hit streak that ranks fifth all time in the modern era. Hampered by various injuries, Molitor only played in 118 games during the ’87 season. Yet he still managed to lead the league with 114 runs scored and 41 doubles. He batted .353 with 16 home runs, 75 RBIs, 45 stolen bases and 164 hits. His 1.003 OPS was a career best. If he’d played in the 160 games he logged during the 1993 campaign, who knows what he could have accomplished during his age 30 season.

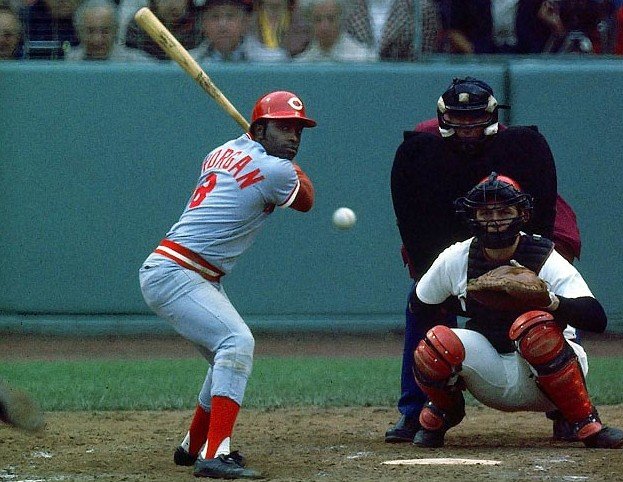

2.) Joe Morgan, 2B (Cincinnati Reds, 1975)

Little Joe rubbed some people the wrong way during his post-playing broadcasting years. I’ll admit that he could sometimes come across as arrogant and repetitive, but his instructional book “Baseball My Way” was one of the formidable reads of my childhood. I checked it out at least a dozen times from my elementary school library and soaked up Joe’s take on everything from proper sliding technique to what color socks to wear when playing ball (white, to avoid possible infection from dyed socks if cut on the playing field). And as a ballplayer, Morgan had a two-year stretch during the 1975-1976 seasons that rivals any player in history. His ’75 season was arguably better. With 132 walks and a .466 on-base percentage to complement 17 home runs, 94 RBIs and 67 stolen bases, I’ll take Joe as my No. 2 hitter any day.

3.) Hank Aaron, LF (1963, Milwaukee Braves)

I’ll admit, I cheated a little bit on this selection. Hammerin’ Hank played 2,174 games in right field during his 23-year career and only 315 games in left. But during all-star games in the 1960s, when the National League assembled perhaps the greatest outfield in history, Aaron graciously ceded right field to the exceptionally gifted gloveman Roberto Clemente, with Willie Mays anchored in center. Aaron played 104 games in left during his rookie season in 1954, so there’s no doubt in my mind that he could have hit with similar authority had he settled in the other corner position. As I mentioned before, it’s tough to single out the greatest Henry Aaron season. He won the MVP in 1957, when he batted .322 with a league-leading 44 home runs and 132 RBIs. He led the league in hitting in 1959, with a .355 average, while also knocking in 123 runs with 39 bombs. I think 1963 was Aaron’s best all-around season, when he batted .319 with 44 home runs, 130 RBIs and a career-best 31 stolen bases. But regardless of which season was Aaron’s peak, he’s hitting in the coveted third slot in my all-time lineup.

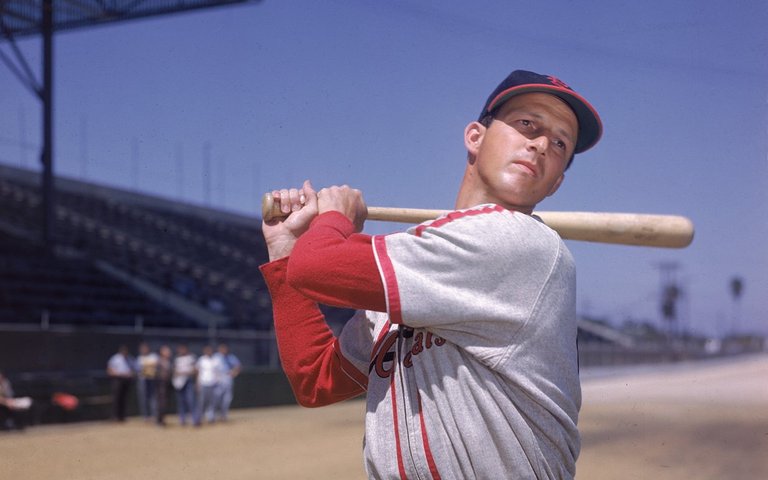

4.) Stan Musial, 1B (St, Louis Cardinals, 1948)

Similar to Aaron, I’m playing Stan the Man out of his natural positon. Musial is less of a stretch though; he played 1,890 games in the outfield and 1,016 at first base. Musial is also similar to Aaron in that he was consistently great during his 22-year career. But Stan had a year for the ages that easily ranks as his career best. In 1948, he led the league in hits (230), runs (135), doubles (46), triples (18), RBIs (131), batting average (.376), on-base percentage (.450), slugging percentage (.702) and total bases (429). He would have tied for the home run title—and thus won the Triple Crown—but he had a dinger erased during a rainout that didn’t count as an official game. Regardless, Musial’s 1948 stats are video-game numbers—and I’m not talking about Earl Weaver Baseball.

5.) Mike Trout, CF (2016, Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim)

I’ve watched a lot of baseball since I first became interested in the sport at age 6, during the 1987 season. Since that time, there have been two players in their early 20s who immediately struck me as potential candidates for the top 10 players of all time. One was first-ballot Hall of Famer Ken Griffey Jr., who broke into the league in 1989 and finished with 630 home runs. Had he not been stricken by freak injuries, he could have easily entered Cooperstown as the all-time home run leader. The only player since Griffey I’ve seen in my lifetime who deserves comparison is Mike Trout. He’s won two MVP awards thus far, but to my mind he’s been the best player in baseball every year since he entered the league. But it’s boring to vote for the same guy every year, especially when his team doesn’t make the playoffs. Fellow center fielders Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays fell prey to similar logic. They were so consistently great year in and year out that they each could have won 10 MVP awards. Trout, while he lacks Mays’ throwing arm as an all-around five-tool stud, could very well surpass the Mick on the all-time CF list by the time he hands in his cleats.

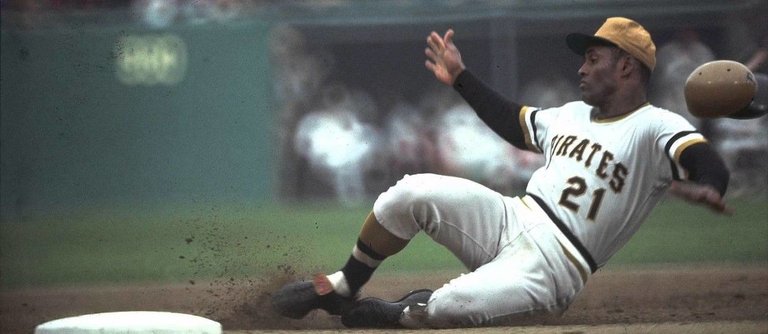

6.) Roberto Clemente, RF (1967, Pittsburgh Pirates)

During my baseball apprenticeship in the late ’80s, I endlessly watched a straight-to-video documentary called “The Golden Greats of Baseball.” At roughly 45 minutes, it’s a concise history of the game, featuring brief individual segments on a who’s who of Hall of Famers. I wore out the VHS tape rewinding the section about Roberto Clemente, whose choreography on the field was an unmatched combination of grace and reckless abandon. As a hitter, the classic Clemente scene featured a lunging smash of an outside pitch to the opposite field gap, his helmet flying off to reveal his Pirates cap as he stretched a double into a sliding triple. In the field, his rifle throws from the warning track to nail runners at the plate were bettered only by his signature play—a running catch of a fading line drive in the right-field corner, followed by a balletic counterclockwise whirl and a cannon blast from his right arm to cut down the runner at third base. Clemente won 12 consecutive Gold Glove awards from 1961 to 1972. He was the National League MVP in 1966, but his best season came in 1967, when he led the league with 209 hits and a .357 batting average, while tallying 23 home runs and 110 RBIs.

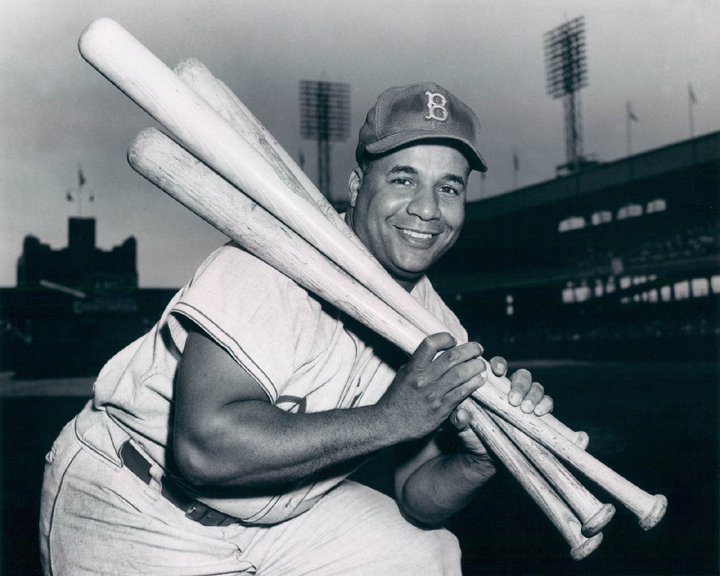

7.) Roy Campanella, C (1953, Brooklyn Dodgers)

Campy’s career is one of the great what-ifs in Major League history. He played eight seasons in the Negro Leagues before joining the Dodgers in 1948, the year after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. After only 10 seasons in the big leagues, his career was cut short by a car accident that left him paralyzed for life. But his prime seasons rival those of Johnny Bench and Yogi Berra. He won three MVP awards, but his career year came in 1953, when he batted .312 with 41 homers and a whopping 142 RBIs. Campanella threw out 57 percent of baserunners during his career, which is the best caught-stealing percentage of all time.

8.) Brooks Robinson, 3B (1964, Baltimore Orioles)

Speaking of great defense, at the hot corner is the guy known as the “Human Vacuum Cleaner.” The segment in “The Golden Greats of Baseball” about the 16-time Gold Glove winner immediately preceded the Clemente section and was punctuated by the best play I’ve ever seen from a third baseman. Robinson gloves a chopper down the line a good five feet behind the bag; his lunging momentum carries him several feet into foul territory, but he still manages a cross-body heave that reaches first base on a pure hop and gets the runner by a step. Brooks was no slouch at the plate, either. His best season was 1964, when he hit .317 with 28 dingers and 118 ribbies, while collecting the fifth of those 16 consecutive Gold Gloves.

9.) Ozzie Smith, SS (1987, St. Louis Cardinals)

With Brooksie at third and Ozzie at short, nothing is getting through the left side of this infield. During his 19 seasons in the big leagues, Osborne Earl Smith mustered only 28 home runs, yet he won 13 Gold Gloves. He also did sneaky damage at the dish and on the base paths, compiling a decent .262 career batting average with 580 stolen bases—22nd on the all-time theft list. In 1987, his best offensive season, he hit .303 with 75 runs batted in, despite posting a goose egg in big flies. The Wizard of Oz was my favorite player as a kid. I collected 174 distinct Ozzie Smith baseball cards, including his coveted rookie card, which had a book value of around $75 when I received it as a Christmas gift in the early ’90s. I grew up in New England—American League country—during the dark ages of national baseball coverage, so I only saw him play a few times a year on TV. But I sought out his name religiously in the newspaper box scores every morning. If there was at least a 1 in the hit column, it was a good day.

P: Pedro Martinez (2000, Boston Red Sox)

A strong case can be made that Pedro Martinez had the best back-to-back pitching seasons of all time in 1999 and 2000. Based on pure statistics, Walter Johnson’s 1912 and 1913 seasons are hard to beat. In 1912, the Big Train went 33-12 with a 1.39 ERA, 0.91 WHIP and 303 strikeouts. In 1913, he posted a 36-7 record with a 1.14 ERA, 0.78 WHIP and 243 strikeouts. Pedro, in comparison, went 23-4 in 1999, with a 2.07 ERA, 0.92 WHIP and 313 strikeouts. In 2000, he was 18-6 with a 1.74 ERA, 0.74 WHIP and 284 strikeouts. But Pedro accomplished his feat during the height of the steroid era, when juiced-up hulks were hitting light-tower shots with alarming regularity. And he did it while standing 5 feet 11 inches tall and weighing 170 pounds sopping wet. Pedro was part scientist, part artist on the mound, with an electric heater, a knee-buckling curve and a protean changeup he could locate in any part of the strike zone. During an offensive era, when baseball’s integrity nearly crumbled under the weight of its players’ inflated muscle mass, Pedro was an everyman hero with a superhuman right arm.

So there it is. As I mentioned before, the above squad by no means represents an all-time greatest team. That roster would probably look something like:

1. Rickey Henderson (LF)

2. Honus Wagner (SS)

3. Babe Ruth (RF)

4. Ted Williams (DH)

5. Willie Mays (CF)

6. Lou Gehrig (1B)

7. Mike Schmidt (3B)

8. Johnny Bench (C)

9. Rogers Hornsby (2B)

P: Walter Johnson

Could my team match up with those all-time greats? Over a seven-game series, the odds say no. But I’d take my roster against any 10 men, from here to eternity.

This post has been ranked within the top 50 most undervalued posts in the first half of Feb 05. We estimate that this post is undervalued by $6.43 as compared to a scenario in which every voter had an equal say.

See the full rankings and details in The Daily Tribune: Feb 05 - Part I. You can also read about some of our methodology, data analysis and technical details in our initial post.

If you are the author and would prefer not to receive these comments, simply reply "Stop" to this comment.