I’d like to tell you the story of how I became a best-selling author.

I didn’t plan it. Didn’t expect it. It came out of the blue, courtesy of a friend, and it changed my life completely.

The story begins with this picture of a Vet garbed in green plastic with his arm up the rear end of a cow. I took it forty years ago when I was a BBC producer.

He was no ordinary Vet. He was James Herriot, one of the highest paid authors in the world. So much for the exotic life of a best-seller.

His friendship and advice put me on the royal road to freedom. The freedom I’m speaking of comes from knowing that for the rest of your life you will make your living from doing what you love best: writing for publication.

I never wanted to go to the north Yorkshire market town of Thirsk in the first place. My wife Mary was in hospital for a minor procedure. I only went because a colleague had gone down with flu.

Thirsk was on a branch line. I remember the station as non-descript. The taxi took me past one or two modern factories and an old-established racecourse to a beautiful cobbled square where I’d booked a room in a hotel.

My spirit lifted when I was told that this hotel had been frequented a century before by one of England’s greatest wits, Sydney Smith. He was the reverend gentleman whose idea of heaven was eating pâté de foie gras to the sound of trumpets.

Among the local celebrities that my production assistant had earmarked for me to interview was a Veterinarian. I was told he was well known. Locals were surprised I hadn’t heard of him. He had written about his experiences as a Vet in the nineteen-forties.

Having unpacked, I walked from the hotel past a parish church and round a corner to the Vet’s practice. My life was due for a drastic change. I was about to enter a legend.

The house was large and ramshackle. James Herriot was there to greet me. His real name was Alfred Wight.

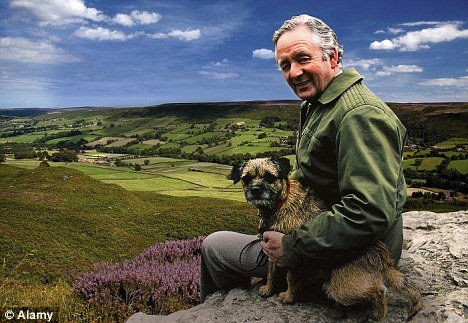

He was a pleasant-faced Scot, stocky, of medium height, neat greying hair, teeth slightly uneven at the edges and with a noticeable burr in his speech. His eyes seemed to grow small and sink into his face when he smiled which was often. He was relaxed like a cat in front of a fire.

We ascended the stairs to the top floor so we could chat in peace and quiet. This was where he and his wife Joan, the Helen of his stories, lived when they were first married. There were facilities for “a cup of Yorkshire tea” for which I was grateful.

I soon decided he’d do nicely as an interviewee. He’d worked in the area since 1940 so, like a doctor, he would know what went on there. He spoke fluently. His contribution wouldn’t need much editing when we recorded the next day.

It took me a while to realise how successful an author Herriot was because of his innate modesty.

He was full of surprises. For instance, he had not started writing until he was fifty yet he’d already sold 50 million books which were the basis of a fine TV series and major movies. I wondered why on he was working as a full-time Vet in an obscure little town in northern England.

As I was leaving, I chanced to mention that I’d written a few books of a specialist nature.

“Is that so?” He sounded genuinely interested. “Would you care to look through one of my books?”

I was hoping he’d say that. I’d intended to buy a copy from the local bookshop and read it overnight.

“Here,” he said, with a smile, “glance through this and let me know if you think I have any talent.”

I slept little that night. His book had a feel for time and place. It was full of brilliant characters and a special love for the Yorkshire countryside, which I was already beginning to appreciate. He wasn’t only interested in animals; he understood people’s whims, dreams and concerns.

The book came to me not simply as a great pleasure, the sort you get from meeting a new and exciting author for the first time. It was slowly casting a light on my future career.

A couple of months later, I returned to Thirsk to make a series of programmes exclusively on Herriot.

Such joyous days. I travelled with him to the hill farms, opening and closing several gates on the way. I joined him in the fantastic world he had captured in books like All Creatures Great And Small. He jokingly complained that each visit on those stony roads cost him more on repairs to his car than the odd pound sterling farmers grudgingly forked out for his services.

They had no idea that each of his visits probably cost him £1,000 in taxes he could have avoided by emigrating.

It impressed me that the tough hill-farmers grasped they were part of the legend this man had become. They didn’t call their “vit’nry” by his real name but by “Mr 'Erriot”, his pen name.

One evening, we were driving home with Dan, his black Labrador, in the back when he noticed his little Terrier, Hector, was missing.

That was the only time I saw him panic. He turned round and drove like crazy to the farm we’d just left, bumping up and down. It was a relief to see Hector jump into his arms.

Incidentally, Herriot’s black Labrador called Dan was later resurrected in my Bless Me, Father stories in the shape of Pontius, the black Labrador of Fr. Duddleswell’s neighbour, Billy Buzzle, the bookie.

Herriot used to say of animals, “If having a soul means being able to feel love and loyalty and gratitude, then animals are better off than a lot of humans. I hope to make people realize how totally helpless animals are, how dependent on us, trusting like a child that we will take care of their needs.”

Even the Vet’s partners joined in the make-belief. When I asked his senior, Donald Sinclair, to autograph one of Herriot’s books, he wrote, Siegfried Farnon, the name Herriot had given him in his books.

Herriot had given Siegfried and his brother Tristan who both figure prominently in the books a share in his royalties.

At his time, my wife was expecting our first child. We didn’t know if it was boy or girl so Herriot inscribed my copy of his book It Shouldn’t Happen To A Vet with “For Francis or Frances”. “Let me know which it is,” he said.

Before long, I sent him a telegram: “It’s a boy.” He replied by return: “Hope you had a good Vet in attendance.”

In spite of his immense royalties, he was never tempted to live abroad. He and Joan decided it was better for him to be “a moderately happy Vet in Yorkshire than a miserable exile sunning himself all day in the Bahamas.” He did receive the OBE, Officer of the British Empire, conferred on him by Prince Charles in 1979.

"I wrote six books at 83 per cent tax,” he told me, “and my accountant said, Five of your six books you wrote for the tax man.’”

In the Nineteen-Seventies, the UK’s top rate of income tax rose to 83 per cent and 98 per cent when an investment income surcharge was applied. There was an exodus of entrepreneurs and top entertainers. David Bowie went to live in Switzerland and the Rolling Stones left for the South of France.

Herriot did confess that he treated himself occasionally. “I’m now well off enough,” he said, “to buy a jacket without M&S on the label.” Marks & Spencer, a middle-of-the-road food and clothing British store, was the favourite of P.M. Margaret Thatcher, the Iron Lady.

The one thing he hated about being a vet was putting sick animals to sleep. He was relieved that being now a senior partner, he could leave that job to a junior.

He stands out in my memory as a kind, open, caring human being who was not only patient with me but with the many visitors, mostly from the USA, who turned up in Thirsk where he worked. He walked them up and down the garden a few times, signed the books they’d bought in the local shop, walked them to their cars or buses and waved them goodbye.

James Herriot treated me with special kindness. When I sent him a little illustrated children’s fable of mine called The Best Of All Possible World, he wrote back:

Your fable is perfectly enchanting and I loved it. I do congratulate you and wish you and it every success. I enclose a few quotes from the “famous Yorkshire author” with the hope that it may take off in America. Maybe another JONATHAN LIVINGSTONE SEAGULL? Stranger things have happened and your book is immeasurably better than that one.

Love to Francis and warmest regards to yourself. Yours aye, Alfred

What did I learn from James Herriot? First, that the public are interested in a small world of ordinary people if it is presented with humour and sympathy. He had a knack of taking the most mundane incident and humanizing it to a universal level.

For instance, he told me the story of an old woman who called him to treat her sick budgie. When he got to her place, he noticed it had died. He quickly picked it out of its cage and apologized for leaving his medicine in his surgery. He drove back to town, bought another budgie, returned to the woman and said the medicine had worked. Delighted at its sudden revival, she didn’t notice it was a different budgie.

I remember the afternoon in the Yorkshire Dales when he said, ‘Have you been a BBC producer for long?”

No, I told him. I’d been a Catholic priest for ten years.

“How interesting,” he said, “Have you ever thought of writing about your experiences?”

“Never,” I said. I’d thought about writing novels but nothing autobiographical.

“What was it like being a Catholic priest, Peter? Funny, sad, humbling, upsetting, exhilarating , challenging …?”

“All of those things and more,” I said.

“Sounds to me like a great basis for a book, Peter. Why not give it a try?”

He advised me not to tell all my tales in one book. “Keep the way open for follow-ups.” He also advised putting the stories in the past, the almost forgotten times, where fond memories and nostalgia reign.

When he decided to write his books, over a three-year period he’d tried 87 publishers and magazines and sold nothing until he got an agent. His wife Joan told me how depressed he was whenever a manuscript came “thudding back” from a publisher with a curt note, “No thanks.” Herriot told me it was vital to get myself an agent.

He had chosen to use a pseudonym for a number of reasons. One was so that his clients wouldn’t claim he was gossiping about them. He chose the name of “James” after his son and “Herriot”, the Birmingham City football club goalkeeper in the 1952 Cup Final.

When I came to write about my own small clerical world, I chose the name Boyd. William (Bill) Boyd was my childhood hero, a silver-haired cowboy with a golden stallion called Trigger, known as the smartest horse in the movies. The short name Neil meant the name would be just that bit bigger on the cover of the book. Now all I had to do was complete the first volume!

In those days, I travelled to the BBC in London on a smoke-filled ill-lit train. All I could do was sketch out some clerical stories that were to become Bless Me, Father. But first, I had to get a grip of the main characters. My years as a priest gave me a big reservoir to choose from.

First, the locale: London. Name of parish: St Jude’s, the patron of hopeless causes. Parish priest, an Irishman, Father Duddleswell. Unlike Chesterton’s Father Brown, he doesn’t solve mysteries, he creates them. The curate, Neil Boyd, newly ordained, naïve, the perfect foil for the mischievous Parish Priest who doesn’t exactly lie but tells the truth in small slices. The housekeeper: Mrs Pring, a widow, was more than a match for Father Duddleswell in repartee. According to Father D, “she can beat eggs just by talking to ‘em.”

Next, Father. Duddleswell’s oldest pal, Dr. Donal Daley whose talent is drinking a glass of whiskey while smoking a cigarette. When Father D says, “You can give up the whiskey, Donal. Didn’t the Lord say faith can move mountains?” ‘True, Charles,” says the Doctor, “but isn’t that tirribly dangerous for mountaineers.”

Next comes the straight-laced Bishop O’Reilly who complains of young women receiving Holy Communion in a blouse with a V-neck “wider than a duck’s wake”.

Now meet Mother Superior, a nun with a Siberian smile, who can put the fear of God into God. And, for local colour, Billy Buzzle the Bookie who lives next door. He owns a dog called Pontius, a black Labrador based on Herriot’s dog Dan. Pontius has the annoying habit of entering the church in hot summer days and walking down the aisle to the sanctuary and jumping on the lap of Bishop O’Reilly.

Having settled on the cast of characters came the time for plotting. Once you know your characters inside-out, the plots usually write themselves.

When the book was finished, I sent it to Lady Collins whom her friends called Pierre. She had accepted five of my books for the Collins Fontana series. I went to see her hoping to get her approval of my autobiographical novel, Bless Me, Father by Neil Boyd.

She thought it was rather old fashioned with not enough appeal to non-Catholics.

Waiting in Lady Collins’ outer office was a tall distinguished middle-aged gent. He must have noticed my down-in-the-mouth look.

“No good?” he asked.

I said, “Not this time.”

He introduced himself. “Donald Copeman, literary agent. Mind telling me what your book’s about?” I gave him a quick resumé. “Sounds interesting. You have another copy? Good. Mind if I take this away with me?”

A few days later, a letter arrived. Donald had persuaded a London publisher to accept it. He enclosed a receipt for £350 minus his ten per cent and a cheque for the advance. I’d never had an advance before. It dawned on me that if had stayed with Collins, I would not have used an agent, my book would have been in Collins’ theology section and brought me in scant royalties.

Lady Luck continued to show her hand. Graham Lord, the formidable book editor of the Sunday Express, later told me what happened.

He had been through the week’s books on his desk for reviewing and threw them one by one on the floor. Looking for something to write about he went through them again and his eye stopped on Bless Me Father. It was the only one whose author was new to him. He called my publisher who would only tell him this was a pen name. I didn’t want the BBC to know I was writing on the side.

Somehow Graham found that I worked at Broadcasting House in London. Pleased with his investigative powers, he wrote in his review that he had found the clerical version of the Herriot books. He said of me “his fond, gentle, anecdotal style closely resembled those of James Herriot”.

That Sunday, the headline of his book review was WHAT A WIFE TOLD THE PRIEST IN CONFESSION. I feared my fellow Catholics would be scandalized, thinking an ex-priest was committing a major crime: betraying the secrets of the confessional. I hastened to assure them this was fiction.

The chapter Graham highlighted was the one in which Fr. Duddleswell entered the confessional wearing his new cordless mike that the curate had persuaded him to buy. He unwittingly broadcast the confession of Mrs. Conroy the butcher’s wife whose husband was in the congregation. She admitted adultery with Mr. Bottesford the local undertaker who at that moment was busy scuttling down a side aisle and out of the church.

He must have phoned Herriot because he went on, “Indeed it was Herriot himself who first encouraged Mr de Rosa to write. Peter, he said, asked me how I started and I told him, and I said, ‘Why don’t you do the same thing? I also advised him not to make the mistake of shoving all his experiences in one book. Mr. de Rosa says Mr. Herriot is ‘a sort of latter-day Saint Francis.’”

My agent arranged with the Sunday Express, Jimmy Kinlay to publish four extracts from Bless Me, Father, beginning the following Sunday. The fee was bigger than my annual salary at the BBC.

On the Monday after the first extract appeared, Donald received enquiries from BBC TV and London Weekend Independent TV. Corgi was one of several paperback publishers who expressed an interest. The possibility of a new Herriot seemed attractive to them.

Time passed. The book was about to be published. Between James Herriot and me a close bond had formed. Herriot must have been in touch with Graham Lord, for he wrote to thank me “for putting on that lovely little broadcast again (about his practice in Thirsk.).”

He added:

I was extremely interested to hear that you had a book coming out and absolutely fascinated to learn that St Martin’s Press in America had made an offer for the first two volumes to be published as one. That is exactly what happened to me. In the process their President Tom McCormack made me out of nothing because my first book was limping along with gross sales of 1,200 copies. If I can help with quotes etc. please let me know.

When I sent him a copy, he responded with his usual generosity:

Your book is great. It has taken me a hell of a time to get round to reading it because I have been up to the neck in lambing time and desperately trying to get my book VET IN A SPIN off to the publishers, but now for a few nights I have had the utter joy of reading BLESS ME, FATHER in bed.

I tell you it is a winner and I only hope that the quotes I enclose are not too late for the next edition that is if they want them.

I feel sure you are on to something big and there is an uncanny similarity with my own experience; the serialization in the Express, Graham Lord’s enthusiastic review and your being taken up by St Martin’s in the USA. I may be simple in many ways but I think I know a first class writer when I see one and you are that thing.

I never dreamed that such sheer fun lurked under your rather quiet exterior. Father Duddleswell and all the other lovely characters are superb. The bed rocked as I read and I’m sure a lot of people are going to tell you the same thing. You have got it – the magic something – and I don’t see you can possibly miss.

Best of luck and I’ll be looking out for you. Yours sincerely, Alfred

His quotes were as follows: “A long, gentle breeze of humour with frequent bursts of helpless laughter ... Neil Boyd has an almost divine gift for extricating deeply satisfying fun from tiny things ... wonderful, real, lovable characters.”

I had a plum job at the BBC HQ in London. I was working with some of the stars of stage and screen, including John Gielgud and, my favourite, Paul Scofield, fresh from winning the Academy Award for his role in A Man For All Seasons. I was surprised when Donald suggested I become a professional writer. Mary and I now had two small boys. If I was a 15-minute wonder, I couldn’t return to my staff job at the BBC.

With Mary’s agreement, I told Donald I’d consider his proposal if he could guarantee me the equivalent of three years salary at the Beeb. This he did within three days. The bonus was that Michael Grade at London Weekend would like to have a script from me with a view to making a series for a sit-com.

This was a tough assignment. I’d never thought of myself as particularly humorous. Besides, I had never seen a sit-com made. I didn’t even like the genre.

Then I remembered my father. In the early 1930s, our family had emigrated to Scranton PA in America where I was conceived and where my grandfather worked as a blacksmith on the Pennsylvania State Railway. My dad had no qualifications. When he applied for a job, he was asked, “Can you do this or that?” “Done it all my life, sir.”

During the Great Depression, he was made foreman of a fertilizer factory. Part of his jobs was shooting horses for the military, and turning them into fertilizer. Hell, I thought, all I had to do was write a TV script.

Words of American author Ray Bradbury came to me: “Sometimes you just have to jump out the window and grow wings on the way down.” Orson Welles claimed his only preparation for directing “Citizen Kane” was watching John Ford’s “Stagecoach” forty times.

I asked a fellow BBC producer in the TV comedy department to let me have a copy of a sit-com. He sent me a script of “Porridge”. This starred Ronnie Barker, one of the best comic actors on UK TV. The writing was so brilliant, my spirits sagged as never before. There was practically a laugh a line.

For the first TV episode I chose the chapter “Breaking the Seal”. To my surprise, within days I was asked to write a series of seven. They were going into production without making a pilot.

Lady Luck once more drifted into view. After years of being Captain Mainwaring in the hit TV show “Dad’s Army”, the UK’s most admired comic actor, Arthur Lowe was showing an interest in playing Father Duddlesell. The press was intrigued at the prospect of Arthur exchanging Home Guard battledress for a black suit with a clerical collar.

A few days later, the phone rang and a voice said, “I want you to teach Captain Mainwaring to become a Catholic priest.” This was how David Askey, my Producer/Director way, told me he’d signed Arthur Lowe.

The choice of the curate was an unknown actor called Daniel Abineri. He was only nineteen years old, far too young to be ordained a priest, but his innocence and inexperience was the perfect foil to Father Duddleswell’s mischief making.

My first job was to prepare Arthur for his ordination. He had to learn how to dress as a priest, say mass, genuflect, make the sign of the cross and say Grace at meals.

He began by thinking that he would have to perform with clerical starchiness like a character in Trollope’s Barchester Towers. He was relieved to learn that Fr. Duddleswell of St Jude’s was much more relaxed.

“I’m glad,” he quipped, “because I am Lowe-church.”

When he genuflected his knees hardly touched the ground. When he blessed himself or the food on the table, an angel would find it hard to realize he was making a sign of the cross. The perfect pupil, he picked up these mannerisms instantly and added others of his own devising.

He was not so pleased to discover his moustache which, like his hair had been dyed ginger for ‘Dad’s Army”, would have to go. “Still,” he said, brushing it fondly, “one has to make sacrifices for religion’s sake.”

After the first rehearsal, one of his co-stars, Dr Donal Daley who was from Northern Ireland, said to me, “Dear God in heaven, he is just like me parish priest back home in Omagh.”

The Director’s only fear was that Arthur who had never played an Irishman before might not manage the brogue too well. As soon as he read from the text, our fears slipped away. His accent wavered occasionally between Dublin and Belfast but, great professional that he was, he made the accent so light it upset no one. The show’s popularity in Ireland north and south was proof of that.

Playwright Dennis Potter used to say that in a book, you deal with an individual. In TV, you are dealing with millions at the same time. Potter thought TV could become the country’s national theatre.

Though Arthur’s most memorable role was as Captain Mainwaring in “Dad’s Army,” he told his agent and his son Steven said that of all his roles he liked Fr. Duddleswell best.

Arthur’s fame guaranteed TV rights to forty countries – from the PBS in the USA to Zimbabwe. The books were translated into many languages. Reader’s Digest spread it round the world with a short version of a chapter from all five books. For this I was paid a dollar a word and most of them were not even mine.

I read that John Le Carré’s first experience was worse. Having one of your books turned into a movie, he said, is like seeing your oxen turned into Oxo cubes.

One reward of writing is the appreciation of readers who say you have enhanced their life in some way. An elderly widow from Fulham in London sent me a letter. It still brings a tear to my eyes in spite of her unintended humour.

I wish to thank you for the pleasure which your books give me and I am positive I have not laughed so much since I lost my husband several years ago. This is a bungling composition and I wonder whether I should send this but I hope you will recognize it as an outcome of gratitude and sincere admiration, With Sincerity,

I was pleased, too, to receive a fan letter from Northern Ireland. It said that during the Troubles, Bless Me, Father was the only TV program everyone, Catholics and Protestants, could laugh at.

By now, my agent had arranged contracts amounting to ninety times my current annual BBC salary. This introduced me to a new phenomenon: money. One proof of this was that I who had rented till now could write out a cheque for a house. No need for a 25-year mortgage.

I was used to an austere life. The religious discipline of my early days and the experiences of the Blitz and food rationing as a child have never left me. I only ever wanted to be an author. It was dawning on me that I could fulfil my dream and spend my entire life writing.

It seemed almost surreal when my newly acquired accountant advised me to talk to lawyers. James Herriot, remember, had alerted me to the fact that Britain had the severest tax regime in the world.

Until I joined the BBC, I’d never earned enough to pay a penny in income tax. Nor had I ever met a lawyer face to face, except a canon (church) lawyer. And now in the room with me were three big London lawyers with different briefs. They outlined options on how to keep as much of my income as possible from the clutches of the tax authorities.

Among the possibilities on offer were to in ships’ containers, move to Jersey where income tax was 20 per cent, emigrate to the Cayman Islands or the Bahamas. It reminded me of what the famous economist John Maynard Keynes said, “The avoidance of taxes is the only intellectual pursuit that still carries any reward.”

There was one other possibility. I could cross the Irish Sea and live in Ireland. My school and college chums had been chiefly Irish. My wife’s father came from Co. Mayo and three of her uncles were still ministering as priests there.

The extra advantage was that if the Irish Finance Minister considered that my books made a cultural contribution, my literary earnings would be free of tax. Other sources of income, including investments and journalism, were taxed.

I was accepted. In Ireland at that time, there were no house taxes, no water charges, car tax was £5 a year and petrol was 70 pence a gallon.

Until recently, I had nothing. Now I was able to buy High Valley, a 4,000 square-foot ranch-style house with an acre of landscaped garden.

It was in the heart of County Wicklow known as the Garden of Ireland with glorious views of the Blue Mountains. Across the valley, was the picturesque Devil’s Glen.

In County Wicklow, the place we lived was known locally as the Valley of the Writers. My next-door neighbour was Catherine Gaskin. Opposite me were John Gardner, thriller writer, and Gordon Thomas who specialized in catastrophes, as well as Anne McCaffrey who specialised in sci-fi. A few miles north lived Frederick Forsyth, Susan Howatch and Hugh Leonard, a distinguished Irish playwright. It was a small world. Hugh used to say, “Ireland is not a good place to have a mistress.”

I last spoke to Herriot on the phone in late 1994. His writing days were over and he no longer able to help out in the practice, free of charge. He died of prostate cancer a few months later. He was seventy-five.

Living in Ireland, I didn’t hear till after the funeral. I wrote to his son James, offering my condolences. He wrote back saying how much his father had enjoyed my books.

Until James wrote his father’s biography in 2001, I had no idea that my mentor had suffered from deep bouts of depression since his youth. This was due largely to his relationship with his demanding parents. They had made big sacrifices to send him to a private school and then become a Vet. They thought he’d married below him - his wife Joan had been a secretary. They showed their disapproval by not attending his wedding.

At one point, Alf became convinced that Joan - always an outgoing, even mildly flirtatious woman - was having an affair, though there was not the slightest evidence of it.

There were lots of minor episodes but when son James was in the sixth form, his dad suffered a severe breakdown. It lasted two years and resulted in Herriot having electroconvulsive therapy.

“Once,” James wrote, “when he was having one of these attacks, I asked what was wrong, and he said he didn't know. He couldn't describe it as anything other than ‘overwhelming melancholy.’”

Herriot, the most successful author of his time, sometimes felt he had failed in everything he did.

It made his kindnesses to me and to so many others all the more remarkable. I was but a poor struggling author whom he listened to and helped along the way.

This story was never about me. It was about a great and humble man who by his firm friendship helped me become a fulltime author.

He always said he was 90 per cent Vet and ten per cent author. The irony is that he made possible for me a great vocation that he did not choose for himself. He saw himself as a Scot who found his deepest happiness working with animals among the moors and dales of Yorkshire, now known as Herriot country.

In the light of my experience, I have a couple of last word of advice for anyone keen to be a professional author.

As priority, get yourself an agent. When my first agent died, the second also proved himself a miracle worker. I had written a history of the Popes called VICARS OF CHRIST: THE DARK SIDE OF THE PAPACY. Hardly a money-winner, I thought. My agent thought otherwise. He handed it to a German publisher friend at the Frankfurt Fair. He took my agent’s word for it that he would do well with it. They shook on a US $25,000 advance. The publisher persuaded Der Spiegel, the German equivalent of Time to give it 4-pp spread. It made No. 1 and was on the best-sellers list for 8 months. The publisher immediately bought my next two books unwritten.

I said to my agent, I take 18 months to write a book and you take 15% of the proceeds after a ten second handshake. Before he tried to justify this apparent robbery, I said, “Andrew, if you took 50% you would be worth it.”

My final word to every prospective author should now be obvious from my own experience: Make sure you are born under a sky full of lucky stars.

great post...!!!

very helpful tips....!!!

upvoted...!!!!