A Waring Blender. It doesn't just make smoothies.

Source: Wikimedia Commons contributors

Introduction (aka the hook)

1952 wasn't just the year when Geoffrey Dummer (no relation to the serial killer) proposed the concept of the integrated circuit, the basis for all modern computers. Or the year that the barcode was patented. Or the year that Winston Churchill announced the first British atomic bomb (said to be far more polite than other varieties).

It was also the year when a far more impressive piece of technology — centrifugally calibrated, vortex-producing, electrically-powered, speed-adjustable, metal-bladed, rotating, ice-decimating, homogenizing, emulsifying, a piece of technology that the British preferred to call by the ominous-sounding The Liquidizer — was employed toward the purpose of finally determining the physical seat of the till-then intangible construction called the gene.

But before we go to year 1952, let's go back to 1918, the year when - cough - excuse me - the year when all this - cough cough - pardon me - the year when all this started.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

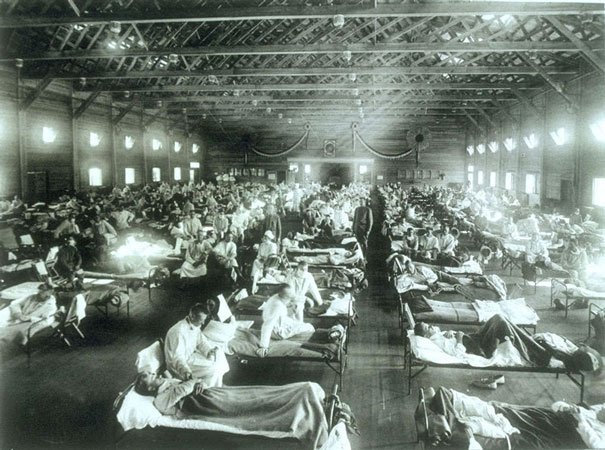

The Spanish Flu.

Source: Wikimedia Commons contributors

The 1918 flu pandemic was an unusually deadly one, killing 3-5% of the world's population.[5] It's no wonder then that scientists took to studying the bacteria responsible for this pneumonia, Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Frederick Griffith, or Dr Death according to a mouse interviewed for this article.

Source: Wikimedia Commons contributors

Frederick Griffith was one of these scientists. His goal was to make a vaccine against pneumonia. What happened was something else entirely.

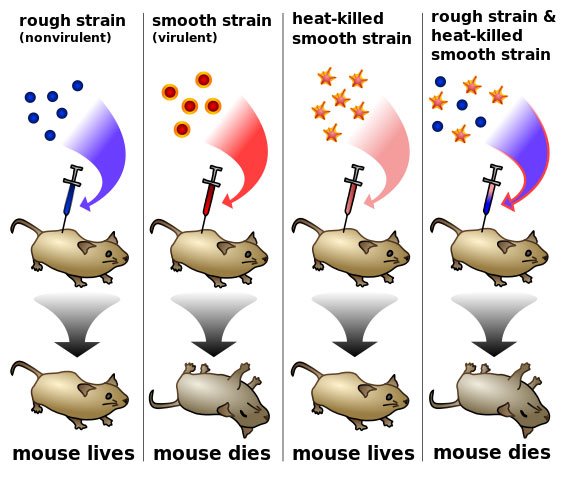

Griffith worked with two strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae, rough (R) and smooth (S). The smooth was pathogenic (it killed the host) while the rough one didn't. (This was because the smooth one was encased in a capsule (called capsid) that protected it against the body's immune system, as was later discovered.) Griffith then did the following experiments[7]:

He injected mice with the S strain, after heating it to high temperatures, causing the bacteria to die. Result? The mice lived.

He injected mice with the R strain. Result? The mice lived, as the R strain was non-pathogenic.

He injected mice with both the heat-killed S strain and the R non-pathogenic strain. Result? Well, what do you think happens when you inject mice with two non-lethal non-pathogenic perfectly harmless strains of bacteria? Of course the mice died: this is science, you rarely get what you expect!

Not only did the mice die, but Griffith extracted the dead mice's blood, and isolated living S strain bacteria from it: yes, that's the strain he never injected. He subsequently injected this into other mice, who also proceeded to die. (Earning him his Dr Death nickname.)

Check out this animation of the experiment if you're a more visual type.

You expect science to validate your hypotheses? Think again, loser!

Source: Wikimedia Commons contributors

After making a discovery he didn't aim to make, and after getting results he didn't expect to get, Griffith was no longer just a scientist, but also felt like one.

Griffith called his discovery the transforming principle, because something from the heat-killed S strain was transforming the non-virulent R strain into virulent S strain. He spends the rest of his life trying to understand what this transforming principle is, making steady progress.

Unfortunately, he never succeeds: you see, it's WWII, and a blitz bomb kills him and a colleague during the London Blitz air raid.[8] Sadly, life is often just like science: it doesn't go as you expect.

Avery, MacLeod, and McCarty's elimination study[9][10]

It was now up to other scientists to prove that DNA was the stuff that did the transforming. Oswald Avery, C. M. MacLeod, and M. McCarty employed several processes to isolate polysaccharides, lipids, RNA, protein, and DNA, to see which one of these transformed the R strain into a virulent S strain. The polysaccharides, lipids, RNA, and protein did nothing to transform the R strain into an S strain. Only the DNA conferred this transformative power (click link to see a pic).

The impact of this study, however, was underwhelming. You see, people still thought DNA was too simple to house something as complex as heredity. Most were thinking it was the protein[10], or some other substance, and that the samples in the experiment above were contaminated (and they weren't wrong, you can rarely really remove 100% of a substance). Here's what James Watson (the co-discoverer of the DNA's structure) had to say about this:

Both Francis and I had no doubts that DNA was the gene. But most people did. And again, you might say, ‘Why didn’t Avery get the Nobel Prize?’ Because most people didn’t take him seriously. Because you could always argue that his observations were limited to bacteria, or that [the transformation of pneumococcus that he described was caused by] a protein resistant to proteases and that the DNA was just scaffolding.[11]

I guess then it's up to that fancy technology quoted in the beginning to prove that DNA is the gene molecule.

The kitchen blender experiments

That's what I call them anyway. Officially they're called the Hershey–Chase experiments or Waring blender experiments.[12]

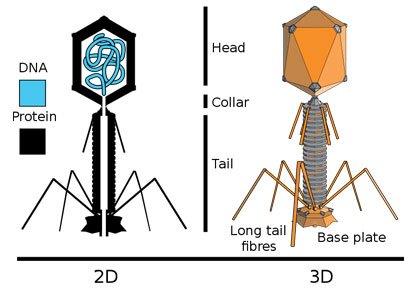

To conduct these experiments, Al Hersey and Martha Chase used T2. And by T2 I do not mean the second installment of Terminator or Trainspotting. I mean the T2 bacteriophage (a virus that "eats" bacteria).

The T2. Much scarier than Arnold, if you ask me.

Source: Wikimedia Commons contributors

What this virus does is it injects something into the host bacteria, which then proceeds to replicate the virus. So the virus somehow gives the bacteria the instructions on how to make more viruses. These instructions are the genetic material.

The virus Hersey and Chase chose is ideal, because it more or less is made up only of DNA and protein. Hersey and Chase sought to prove that it was the protein that housed the genes.[12] But if there's anything we learned from poor Griffith, it's never bet the farm on what you expect to happen in the lab. And also build your lab inside a bunker.

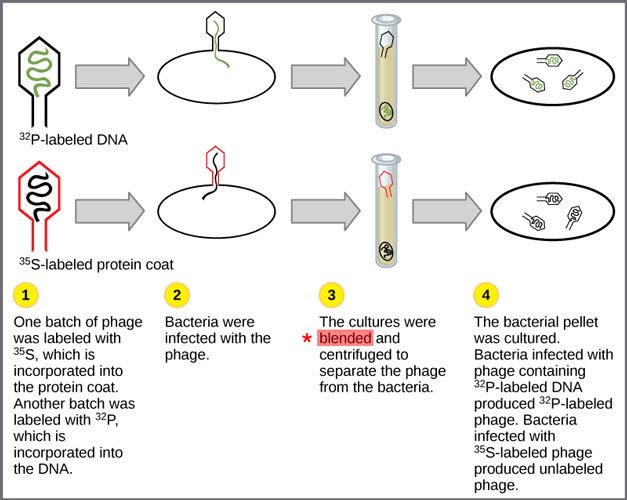

Hersey and Chase's idea was to radioactively label the virus' DNA and protein, and see which of the two entered the bacteria, and which was left out. The thing that got inside the bacteria must be the thing that carries the genetic information.

But how do you radioactively tag just one of the two, either DNA or protein, but not both? What does DNA contain that protein doesn't, and vice versa?

Luckily, there's one thing amino acids (proteins) contain that DNA doesn't: sulfur! And DNA contains phosphorus, which is not to be found in proteins. That's quite fortunate, because these are the only two atoms that DNA and protein don't have in common.

Let's see how they did the experiment in simplified 4-step fashion.

Note the all-important step denoted by the asterisk. The pic here much better illustrates the central role of the blender in these experiments.

Source: OpenStax Biology, modified

Grow the viruses in the presence of radioactive sulfur and radioactive phosphorus, so the virus imbibes this building material to make amino acids (cysteine and methionine are the amino acids that contain sulfur) and DNA.

Add these bacteria eaters to a container filled with bacteria (I know, kinda sadistic). The viruses are going to inject something into the bacteria. Hersey and Chase are praying for protein.

This is my favorite step, cos I can do it at home.

The viruses are currently attached to the bacteria. It's like when you park your car and go shopping, your car is still there, it's not going anywhere without a driver. If you don't find a way to separate the viruses from the bacteria, you're not going to be able to tell what went inside the bacteria and what's merely parked outside it. So Hersey and Chase searched for mighty new technology that could produce the potent forces that wound knock loose the empty virus shells like a hurricane does with trees and houses.

So one day, when Martha Chase was blending a soup or a smoothie (I assume) she was hit by a great idea.

And so, much like in big cities, the cultures were blended, separating the bacteria from the viruses, and then centrifuged in order to get the denser bacteria to the bottom and the lighter empty car-capsids to the top. They pour off the stuff at the top, they culture the pellet at the bottom, and the results come back positive: you have cancer. Also, you have radioactively labeled DNA, which means that's were your genes are.

Curtain close

By now, no one could doubt the results of all these different experiments: DNA was clearly the stuff that carried the hereditary material. For his work, Hersey shared the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (again, it's unclear which of the two). Martha was apparently omitted, being only a lab technician.

Now the race was on to figure out what this DNA stuff was: how it was structured, how something so simple could encode something so complex.

But that's a subject for later posts!

References

1. Wikipedia contributors, "Integrated circuit," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Integrated_circuit&oldid=819422211 (accessed January 10, 2018).

2. Churchill Announces British Atom Bomb http://www.information-britain.co.uk/famdates.php?id=883

3. Wikipedia contributors, "Barcode," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Barcode&oldid=818536291 (accessed January 10, 2018).

4. Wikipedia contributors, "Blender," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Blender&oldid=811737871 (accessed January 10, 2018).

5. Wikipedia contributors, "1918 flu pandemic," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=1918_flu_pandemic&oldid=819441135 (accessed January 10, 2018).

6. Wikipedia contributors, "Streptococcus pneumoniae," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Streptococcus_pneumoniae&oldid=819144795 (accessed January 10, 2018).

7. OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. May 27, 2016 https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:7c2Be-6u@7/Historical-Basis-of-Modern-Und.

8. Wikipedia contributors, "Frederick Griffith," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Frederick_Griffith&oldid=810655281 (accessed January 11, 2018).

9. Avery OT, MacLeod CM, McCarty M. STUDIES ON THE CHEMICAL NATURE OF THE SUBSTANCE INDUCING TRANSFORMATION OF PNEUMOCOCCAL TYPES : INDUCTION OF TRANSFORMATION BY A DESOXYRIBONUCLEIC ACID FRACTION ISOLATED FROM PNEUMOCOCCUS TYPE III. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1944;79(2):137-158. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2135445/

10. Griffiths AJF, Miller JH, Suzuki DT, et al. An Introduction to Genetic Analysis. 7th edition. New York: W. H. Freeman; 2000. DNA: The genetic material. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22104/

11. Oswald Avery’s Pneumococcus Experiments: Forerunner of the DNA Story https://paulingblog.wordpress.com/2009/07/07/oswald-averys-pneumococcus-experiments-forerunner-of-the-dna-story/

12. The Hershey-Chase Blender Experiments https://paulingblog.wordpress.com/2009/08/18/the-hershey-chase-blender-experiments/

13. "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1969". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 11 Jan 2018. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1969/

14. Wikipedia contributors, "Enterobacteria phage T2," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Enterobacteria_phage_T2&oldid=773084983 (accessed January 11, 2018).

Earlier Introduction to Biology episodes:

8: Finding, Counting, and Ordering Genes Using Incredibly Sophisticated Biomolecular Megatechnology

7: Christmas Disease — Yes, it's real, 100% scientifically proven!

6: The Most Famous All-Nighter in the History of Genetics

5: Mendel's Lucky Number Seven — The law of genetics that almost wasn't

4: How Cells Use Logic To Do The Impossible

3 : Armchair Science — The Discovery of Proteins' Secondary Structure

2 : How Cell Membranes Form Spontaneously

1 : Eduard Buchner: The Man Who Killed Vitalism

steemit.chatsteemSTEM is the go-to place for science on Steemit. Check it out at @steemstem or browse the #steemSTEM tag or chat live at

Another great science history post! When you mentioned that Martha Chase was omitted from the Nobel Prize, I looked into whether or not this was gender bias, or simply exclusion of a lab tech. Unfortunately, not much is know about her and her science career was cut short soon after so there isn't a definitive answer to this question.

http://www.themadscienceblog.com/2013/10/gender-bias-in-science-part-iv-martha.html

Just read the article. It's a good one. Kinda satisfying to read it just after I wrote this cos I feel somehow strangely vindicated, like "yeah, that's exactly how it happened". As if there was any debate! Also I have a crisply fresh understanding of the topics.

Also good to know more about Martha Chase. Her divorce and her reaction to it made me sad.

I also found the following passage interesting:

I thought that was dogma, unnecessary to be proved by experiment! It's also part of my whole "the survival instinct does not exist" idea: organisms cannot actively adapt to the environment, they merely present random mutations and survive or die according to whether the mutations are beneficial. If they were mutating in response to the environment that would create a vicious circle and it would be impossible to prove Darwin's theory since it would be tautological.

Yeah I thought gender bias at first as well, but then saw she was a lab technician, and thought, well, they probably won't give a lab technician a Nobel Prize.

Καλημέρα και καλή εβδομάδα... πολύ καλή η ανάρτηση σου

Ευχαριστώ! )

Πολύ καλή δουλειά!! Εξαιρετικό άρθρο θα έλεγα!!

Ευχαριστώ Δήμητρα!

Παρακαλώ!!! 😊

Very interesting article and well sourced, thank you!

@originalworks

Please always upvote my blog bro