Forests are highly complex ecosystems. Trees stand away from each other, although their roots form an underground network. Can they communicate?

Image source

Underground networks

Suzanne Simard is an ecologist who has been researching trees for over thirty years. As a child, she was amazed at the complex root systems in the forests of British Columbia where she grew up. This led her to study forestry. She worked in the industry but was disturbed by the massive clear-cutting that was taking place. (Canada has the highest rate of forest “disturbance” in the world, easily surpassing Brazil.)

Suzanne Simard. Image source

So she went back to study ecology. She found that scientists had discovered that one pine seedling root can transmit carbon to another pine seedling root. This led her to do many experiments on the interaction of various species of trees with each other.

She grew 80 sets of three species of tree: paper birch, Douglas fir, and western red cedar. She hypothesized that birch and the fir would be connected in an underground web, but not the cedar with its different root structure. She sprayed the trees with radioactive carbon-14 carbon dioxide gas and stable isotope carbon-13 carbon dioxide gas. In this way, she was able to see if there was two-way communication between trees.

She was right. The birch and the fir communicated with each other, but not with the cedar. And it was two-way communication.

The language of trees

Simard discovered that although trees send carbon to each other, it was usually asymmetrical. In summer the birch sent more carbon to the fir, particularly if the fir was shaded. At other times when the birch was leafless and the fir still growing, carbon was sent mainly in the opposite direction. In other words, there was interspecies cooperation going on.

Trees with different growth cycles, such as between deciduous and coniferous trees, can loan one another sugars as deficits occur within seasonal changes. This arrangement benefits both species—a kind of co-dependency.

Simard found a massive belowground communications network. So how do they communicate? Suzanne Simard:

How were paper birch and Douglas fir communicating? Well, it turns out they were conversing not only in the language of carbon but also nitrogen and phosphorus and water and defence signals and allele chemicals and hormones—information. And you know, I have to tell you, before me, scientists had thought that this belowground mutualistic symbiosis called a mycorrhiza was involved. Mycorrhiza literally means “fungus root.” You see their reproductive organs when you walk through the forest. They're the mushrooms. The mushrooms, though, are just the tip of the iceberg, because coming out of those stems are fungal threads that form a mycelium, and that mycelium infects and colonizes the roots of all the trees and plants. And where the fungal cells interact with the root cells, there's a trade of carbon for nutrients, and that fungus gets those nutrients by growing through the soil and coating every soil particle. The web is so dense that there can be hundreds of kilometres of mycelium under a single footstep. And not only that, that mycelium connects different individuals in the forest, individuals not only of the same species but between species, like birch and fir, and it works kind of like the Internet.

The family network

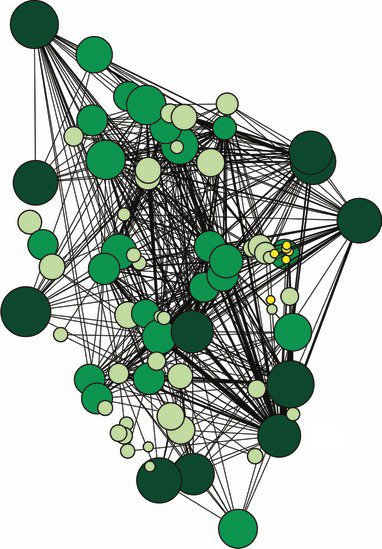

The fungal network looks very much like a computer network diagram. It consists of nodes (trees) and links (fungal pathways).

The fungal network. Image source

In the diagram above, the biggest, dark green nodes are the hub nodes, or “mother nodes”—because they nurture their young, seen as small yellow nodes in the diagram. In a single forest, a mother tree can be connected to hundreds of other trees, sending their excess carbon through the fungal root network to the subterranean seedlings. Seedlings linked like this to mother nodes have four times the survival rate compared to those that don't.

But it gets more interesting. Suzanne Simard:

...it turns out they do recognize their kin. Mother trees colonize their kin with bigger mycorrhizal networks. They send them more carbon below ground. They even reduce their own root competition to make elbow room for their kids. When mother trees are injured or dying, they also send messages of wisdom on to the next generation of seedlings. So we've used isotope tracing to trace carbon moving from an injured mother tree down her trunk into the mycorrhizal network and into her neighbouring seedlings, not only carbon but also defence signals. And these two compounds have increased the resistance of those seedlings to future stresses. So trees talk.

Here's a short video explaining the process:

References:

Yale Environment: Exploring How and Why Trees ‘Talk’ to Each Other

Smithsonian: Do Trees Talk to Each Other?

Kotke.org: The internet of trees: how trees talk to each other underground

Wikipedia: Suzanne Simard

Also posted on Weku, @tim-beck, 2019-02-13

Isn't this interesting. Imagine having those trees speak English? I wonder what they'll have to say against man.

Posted using Partiko Android

I was reading just the other day ,that when plants are )thirsty) in need of water, they send off very high frequency audio signals, above the range humans can hear.

Found your article very interesting, Thank you.