The Actors:

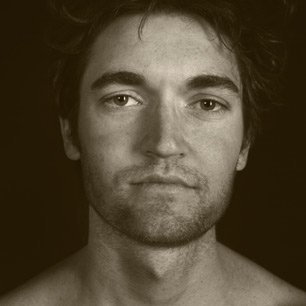

Ross Ulbricht (Dread Pirate Roberts)

George Frost (Bitstamp Lawyer)

Tigran Gambaryan ( IRS Special Agent)

Curtis Green ( Silk Road forum admin)

Kathryn Haun and William Frentzen (Assistant United States attorneys based in San Francisco)

Once Upon a time...

DEA Special Agent Carl Force wanted his money—real cash, not just numbers on a screen—and he wanted it fast.

It was October 2013, and Force had spent the past couple of years working on a Baltimore-based task force investigating the darknet's biggest drug site, Silk Road. During that time, he had also carefully cultivated several lucrative side projects all connected to Bitcoin, the digital currency Force was convinced would make him rich.

One of those schemes had been ripping off the man who ran Silk Road, "Dread Pirate Roberts." That plan was now falling apart. As it turns out, the largest online drug market in history had been run by a 29-year-old named Ross Ulbricht, who wasn’t as safe behind his screen as he imagined he was. Ulbricht had been arrested earlier that month in the San Francisco Public Library by federal agents with their guns drawn.

Now government prosecutors were sifting through a mountain of evidence, and Force could only guess at how big it was. The FBI got around the encryption of Ulbricht’s Samsung Z700 laptop with a street-level tactic: two agents distracted him while a third grabbed the open laptop out of his hands as Ulbricht was working. The kingpin had been caught red-handed, tapping commands to his Silk Road subordinates up until the moment he was cuffed.

Force had been treating Ulbricht like his personal Bitcoin ATM for several months by this point, attempting to extort DPR one day and wrangling Bitcoin bribes for fake information the next. Now, Force didn’t want to be holding those bitcoins anymore. He opened an account with Bitstamp, a Slovenia-based Bitcoin exchange where he thought he could turn coins into cash quickly and quietly.

But when Force opened Bitstamp account #557042 on October 12, 2013, it sealed his fate. He had tricked Ulbricht into paying him more than 1,200 bitcoins (a cache worth more than $700,000 today). Trying to launder those ill-gotten gains through Bitstamp was about as poor a choice as Force could make—though the agent couldn’t have known this at the time.

The investigation of Force ultimately led to a second agent, Shaun Bridges, who worked on the same Baltimore task force and ran an even more lucrative scheme. Incredibly, the two agents were stealing in parallel—friendly co-workers, both tasked to the same case, each apparently unaware of the other’s scheme. One person who helped with the government's case believes there is even more corruption inside the Baltimore task force the two agents worked on. (Neither Bridges nor Force responded to Ars' interview requests for this story.)

This is the story of how they were caught.

Suspicion

Force opened his account at Bitstamp as "Eladio Guzman Fuentes," an undercover identity that he used in his work as a DEA agent. With a Maryland driver’s license, proof of residence, and Social Security card all connected to Mr. Fuentes, Force thought he’d be in the clear.

He wasn’t. The documents ended up in the hands of Bitstamp’s general counsel, George Frost, a journalist-turned-attorney who handles legal matters for the Bitcoin startup out of his quiet backyard office in Berkeley, California. Frost looked at the identity documents sent by "Fuentes," and they didn’t check out.

"I can’t tell you exactly how, but we knew they were sophisticated forgeries," Frost said in an interview with Ars.

Frost confronted Force, who quickly fessed up. He showed Bitstamp his real ID, a Baltimore water bill, and his badge.

"I am a Special Agent with the Drug Enforcement Administration and learned about Bitcoin through my investigation of SILK ROAD," Force wrote to Bitstamp in an e-mail that Frost provided to Ars. "I have attached a copy of my resume and a scanned copy of my badge and credentials."

With that, Frost let him set up an account, but it still didn’t sit right. Even if the guy was law enforcement, Frost wasn’t sure he wanted him around. The just-founded startup didn’t need the headaches of being a launching platform for DEA undercover operations. In the meantime, Force made a couple of large transactions that November, transferring $34,000 and then $96,000 worth of bitcoin into a bank account.

Bitstamp allowed the withdrawals, but Frost continued to be suspicious. DEA credentials or not, Force’s behavior was weird. Frost contacted FinCEN, a bureau of the Treasury Department that collects financial data to uncover possible crimes. The contact at FinCEN was Shaun Bridges, a Secret Service agent whom Frost had worked with previously. (The Secret Service has been part of the Department of Homeland Security since 2003, but was previously under Treasury.)

"[Bridges] was a smart guy and seemed very conscientious," Frost recalled.

Bridges told Frost he would refer the case to the Department of Justice’s Public Integrity Section—the division that deals with public corruption—but nothing seemed to happen after that.

Meanwhile, Force kept moving his assets out of Bitcoin. In December 2013, he paid off his mortgage in full, which had about $130,000 outstanding.

In April 2014, six months after the Ulbricht arrest, Force made another big withdrawal. This time, he retrieved about $80,000. Bitstamp employees went back and looked at Force's IP addresses—they were all connected to Tor, an anonymizing network for Web browsers to surf the Internet seemingly undetected.

"Sometimes there’s a good reason for using Tor, but it’s a big red flag for us," said Frost. (In fact, Bitstamp no longer allows Tor connections.)

Force said he used Tor for privacy, and "he didn’t particularly want the NSA looking over his shoulder," Frost said. It looked fishy, but the withdrawal was allowed.

On April 28, 2014, Force tried a fourth withdrawal. It was his biggest yet, trying to move more than $200,000 in bitcoins. This time, Frost decided to freeze the account until he could get better answers. He had already contacted federal authorities about this agent's behavior, but nothing seemed to be happening.

On May 1, the attorney tried another route. Frost had a previously scheduled a meeting with someone whose eyes wouldn’t roll back when he mentioned Bitcoin. Kathryn Haun, an assistant United States attorney in San Francisco, was DOJ’s first digital currency coordinator. Also at the meeting was Tigran Gambaryan, then a 28-year-old special agent with the Internal Revenue Service in nearby Oakland.

After the meeting, Frost was blunt about his suspicions of Force. "I'm an old reporter and I really smell a rat here," he recalled himself saying.

Haun asked what was up. It had been a long meeting.

"For one thing, he's using his undercover name and undercover credentials," Frost explained.

That was a bit weird. But it was most likely a sign of sloppy undercover work, not criminality. And assigning agents to investigate other agents wasn’t a decision to be made lightly. To Haun, it seemed thin, and she said as much. Still, she told Frost to send on what he had.

Gambaryan was interested, too. The Oakland-based agent was deeply interested in tech in general and Bitcoin in particular. He’d relished the stories of his colleagues who’d worked on the Silk Road case, including fellow IRS special agent Gary Alford, who famously was the first to identify Ulbricht through a little Google-fu.

Gambaryan also knew about tension between Silk Road investigative teams in Baltimore and New York, but Frost’s sudden aside after the meeting raised the prospect that something more sinister than agency rivalry was going on. It was a distant possibility, but still—why, Gambaryan thought, was anyone involved in the Silk Road case trying to cash out large quantities of Bitcoin?

Haun and Gambaryan were on the fence about the value of investigating this at all. But the very next day, Force did something that made an investigation all but inevitable.

"Could you please delete my transaction history to date?" Force asked in an e-mail to Bitstamp’s customer service. "It is cumbersome to go through records back to November 2013 for my accountant."

The request put Frost on high alert. He already suspected this DEA agent had somehow gone rogue, and now it looked like he was trying to destroy evidence. He called Bitstamp's Slovenian service team and told them not to delete anything, then he called Haun. She opened an investigation the same day, still unsure if it would amount to much.

Investigation

With a formal investigation underway, Gambaryan finally found a case that seemed tailor-made to his interests. From the second he’d started working at the IRS Oakland office in 2011, the young investigator would informally chat up various Bitcoin startups, eager to learn more about their industry.

Gambaryan was born in Moscow to Armenian parents, both of whom were Soviet-era officials in the Ministry of Finance. The whole family moved to Fresno, California—a Central Valley city home to a large Armenian community—when Gambaryan was 12 years old. After studying accounting at Fresno State University, he took his first job at the California Franchise Tax Board. Soon after, he wanted to move up the law enforcement ladder; the Internal Revenue Service beckoned.

While Gambaryan was deeply interested in the topic, he’d never actually worked a Bitcoin case before. To investigate Force, he would have to trace digital currency in the same way he had learned to hunt down black market money enumerated in "regular" currency.

"I started looking at it, and I was like: ‘I have no idea what I’m looking at, it’s just a bunch of numbers,’" he said.

He was starting at ground zero but knew it was possible. Bitcoin’s greatest feature was also its greatest liability for would-be criminals: everything was on the record, forever. The blockchain was a giant public ledger.

If Gambaryan could pull Force’s financial records, find the agent’s Bitcoin activity, and then match that with transaction records already locked away in the government’s Silk Road database, he would know whether this was a case. So in an unassuming cubicle in an upper floor of the twin towers federal building in downtown Oakland, Gambaryan began that painstaking process, learning how to follow particular threads of bitcoins moving in and out of Silk Road.

Haun began to work the case as well, situated in the federal high-rise a few blocks from San Francisco’s City Hall. There was an obvious place to start: Shaun Bridges, the Secret Service agent who Frost believed was his friend in the government.

On May 6, the investigative duo got Bridges on the phone. Haun introduced herself and explained the allegations against Force. She expected Bridges to react with, at a minimum, serious concern. Instead, Bridges—who presented himself to Frost and others as the government's point man for all things Bitcoin—questioned her authority.

"What is a federal prosecutor in San Francisco doing investigating anything going on in Baltimore?" he asked, as Haun later recalled in interviews. "Why do you have any jurisdiction here?"

That set off more alarm bells. Haun and Gambaryan had questions about government agents possibly mishandling funds, and now Bridges was getting defensive. Haun recalled herself saying, "What is a Secret Service agent in Baltimore doing going all over the world telling people you're the exclusive point of contact for the US government?"

After they hung up, Haun and Gambaryan agreed that Bridges seemed sketchy. For the time being, though, they had to move ahead with Force’s case—without any help from Bridges, the man who allegedly knew the most about it.

As the days turned into weeks, Gambaryan got ahold of the Silk Road database and immersed himself in the details of Ulbricht’s case, taking note of every interaction that Force had with the drug kingpin. He reviewed Force’s videotaped undercover interactions and case reports. He hunted through every message that Force, in various online personas, exchanged with the Dread Pirate Roberts. He had to know what Force had done on Silk Road to find out whether he took money from the site.

Force’s "official" undercover account—the only one Gambaryan knew about initially—was called "Nob." Using that account, Force got DPR's attention. The method he used wasn’t subtle. He sent a message reading "nob business proposal," stating that he wanted to straight-up purchase the whole Silk Road site. DPR suggested a price of $1 billion, far more than what Nob had in mind. But the somewhat off-the-wall conversation served its purpose—as Nob, Force was able to forge a relationship with DPR.

After a few months of working undercover, Force proposed a deal on December 7, 2012. He complained to DPR that Silk Road sellers only want "very small amounts of drugs" and that "it isn’t really worth it for me to do below ten kilos." DPR then told Nob he would try to locate a buyer for such a large quantity. The next day, DPR wrote back: "I think we have a buyer for you. One of my staff is sending the details."

That unfortunate buyer was a Silk Road staffer named Curtis Green, who would get to know Force all too well.

Three accounts

Under the handle Flush, the then-47-year-old Curtis Green was in charge of the forums on Silk Road—a sort of darknet customer service representative. A Mormon, Green had never used drugs in his life except for the ones he was prescribed for a back injury.

Green might not have been a big fish, but he was big enough. In January 2013, he signed for a package that Force arranged to have sent to him. It contained a kilo of cocaine. When he took the package into his kitchen, he was promptly arrested by a team of about a dozen agents. (Green’s lawyer, Scott E. Williams, told Ars that his client never knowingly took possession of any illegal drugs.)

After a short stint in jail for cocaine possession, Green was bailed out. He was soon propped up in a hotel room by Force and Bridges and grilled for nearly 12 hours. This part of the investigation was above-board: both Force and Bridges were part of the Baltimore Task Force, intent on busting Silk Road. The duo asked Green to spill everything he knew about Silk Road. Without hesitation, the man told them everything—including the password for his account as "Flush."

That same day, someone logged in as Flush and started sending huge amounts of bitcoins to an account called Number13. Other sellers were having bitcoins disappear from their accounts, too. By the time DPR and his most trusted administrator, Inigo, figured out what was going on, roughly 20,000 bitcoins (worth about $350,000 at the time) had disappeared.

DPR went ballistic. He figured Green—who had gone AWOL around the time the theft started—was behind it. When he thought of who might help him teach Green a lesson, DPR naturally turned to the man who had just introduced himself as an experienced criminal: Nob.

Force, acting as Nob, was happy to help. DPR told him: "I'd like him beat up, then forced to send the bitcoins he stole back. like sit him down at his computer and make him do it." But later, DPR changed his mind: "Can you change the order to execute rather than torture?"

Force said he’d do the job for $80,000 in bitcoins, half payable up front. DPR agreed. On Saturday, February 16, 2013, with his wife taking the pictures, Green staged his own death—replete with Campbell’s Chicken and Stars soup to simulate vomit. He was face down on his bathroom floor, his eyes half open.

When DPR got the pictures of Green's fake dead body, he replied that he was "a little disturbed, but I’m ok... I’m new to this kind of thing." The kingpin said he didn’t "think I’ve done the wrong thing," and "I’m sure I will call on you again at some point, though I hope I won’t have to."

Force told DPR that Green had died of heart failure after being tortured. On February 28, 2013, Nob told DPR that Green’s body had been completely destroyed. He asked for the final $40,000 and got it promptly.

That money was handed over to the government. But Force had more ideas about how to get paid, ideas he wouldn't be so forthcoming about.

On April 1, 2013, DPR received this cryptic message from a new account called "Death From Above":

I know that you had something to do with Curtis Green’s disappearance and death. Just wanted to let you know that I’m coming for you. Tuque. You are a dead man. Don’t think you can elude me. De Oppresso Liber.

After a short back-and-forth, Death From Above tried to extort $250,000 from DPR. The messages were from Force. Gambaryan discovered it only because Force had been sloppy—in one of his official reports, he left video footage of himself typing as DFA.

The extortion attempt didn’t work. It took five days for DPR to reply: "Your threats and all of the other aren’t going to deter me . . . stop messaging me and go find something else to do."

Having failed, Force decided to use a carrot rather than a stick. Under the Nob personality, Force convinced DPR that he had access to a corrupt Department of Justice employee who went by the name "Kevin." That month, DPR paid Nob 400 bitcoins (then worth about $40,000) for Kevin’s "counter-intelligence" information. Two months later, DPR paid an additional 525 bitcoins.

In Force’s regular reports to his superiors, known as a DEA "6," the agent described the first payment. But in regard to the second, Force wrote: "DPR made no such payment."

Amongst DPR's and Nob’s July 31, 2013 to August 4, 2013 encrypted messages, which were preserved in the seized Silk Road server, there was only one left in cleartext. DPR noted that he had paid the 525 bitcoins "as requested." Force, as Nob, wrote back just two words: "Use PGP!"

That was enough. Gambaryan could see that a single payment of 525 bitcoins went to another one of Force’s Bitcoin wallets—it happened exactly when DPR said he paid.

"Ross' screwup was what got Carl caught," Gambaryan told Ars.

Force had yet another scheme. He created a third Silk Road identity called "French Maid" and offered to sell DPR information about the government's investigation into Silk Road for another $100,000 in bitcoins. Again, DPR paid. Again, the money went into one of Force’s personal accounts.

It isn’t clear what, if anything, Force told DPR after getting that cash. A daily log file from Ulbricht’s computer mentions French Maid. This document notes that DPR paid $100,000 but didn’t hear back.

Second suspect

On May 30, 2014, Haun led a "proffer" session for Force with Gambaryan at her side. The concept of a proffer is that it allows a defendant to come clean, giving up useful information in exchange for a shorter sentence. It was conducted as a video conference: Haun and Gambaryan were in San Francisco, Force and his lawyer Ivan Bates were across the country in Baltimore.

Force admitted working as Nob and improperly taking bitcoins that belonged to the government. However, he tried to play it off as one big misunderstanding: he didn’t know where or how to transmit them to the government because Bitcoin was a new technology the government wasn’t equipped for. To boot, Force argued that he’d profited on the government’s behalf as the price of Bitcoin went up.

That, obviously, didn’t hold water. A newbie agent might have some confusion about the right way to hold evidence, but this didn’t come close to excusing Force’s behavior.

In an interview, Haun posited a hypothetical: "If the courtroom is closed at the end of the day, and there’s $20,000 cash in evidence, I might not know where to put it," she said. "But I know not to put it in my bank account."

At that point, Haun knew Force had acted illegally, but she still didn’t know how far he’d gone. He was asked directly: "Have you heard of an account called ‘French Maid?’ Have you heard of ‘Death from Above?’" Force denied knowing anything about those accounts.

After the proffer session, opinion was split among the agents and lawyers in San Francisco as to whether Force was telling the truth. For her part, Haun was sure he was lying.

Gambaryan went back to the vast Silk Road database. It took some time, but he was able to confirm suspicions that Force was both French Maid and Death from Above. Force had left the particular version of PGP in his e-mail signatures in his various personae.

Force was finally boxed in. And the fact that he’d lied during the proffer session meant everything said could be used against him.

For his part, Shaun Bridges had continued to engage in odd behavior since that first phone call earlier in the Force investigation. In mid-June 2014, Haun and Gambaryan were at a Europol meeting in the Netherlands. Before returning to California, they decided to fly on to Slovenia and meet with Bitstamp executives in person to discuss the Force case.

By early December 2014, Haun was finally getting ready to charge Force. But then, Gambaryan made a startling discovery: he was able to determine that the 525 bitcoin payment had come directly from Ulbricht himself by manually cross-referencing Force's and Ulbricht's bitcoin transactions. He was able to confirm this with a new website called Wallet Explorer.

This new site, like no other before it, could accurately trace the history of bitcoin payments and wallets. Moreover, it was able to map wallets into known "clusters"—that is, mapping addresses to known entities like Silk Road, Coinbase, and other large Bitcoin players. (Wallet Explorer, and its commercial successor, Chainalysis, made use of academic research that first debuted in October 2013.)

There was more to this discovery. After becoming more comfortable with his blockchain analysis, Gambaryan strongly suspected there was another bad actor. The dozens of hours he'd spent tracing the movements of bitcoins through the blockchain showed some currency being moved in small groups, while others were bouncing around as large chunks. Force had made simplistic transfers of money using his own name. But Gambaryan saw another, more complicated set of transfers as well.

On Christmas Eve 2014, Gambaryan called Haun at 11pm to tell her that there was new, strong evidence to suggest that the Silk Road Bitcoin heist was specifically linked to the Baltimore Silk Road Task Force. The IRS special agent had previously thought that Baltimore was connected somehow, as they were the only ones who had access to Green, but he couldn't prove it.

"It didn't make sense for Green to do it," Gambaryan said. "He was in their custody and cooperating."

But as Gambaryan explained to Haun, one of Gambaryan's colleagues, IRS special agent Gary Alford, had found older correspondence between the two targets: on January 23, 2013, Force had e-mailed Bridges, asking him to replenish a DEA-controlled Silk Road account called "TrustUsJones." Bridges did so from another Silk Road account, "Number13."

It wasn't clear with bulletproof certainty that Bridges and Number13 were one and the same, but it certainly suggested at the very least that the Baltimore Task Force had access to some Silk Road-based Bitcoin accounts. This marked the first time investigators had a clear direction to go in.

Confrontation

As they were considering the charges against Force, Gambaryan and Haun were working under the theory that he had also been responsible for the massive theft from Silk Road drug dealers. After all, he was a known corrupt agent who had been in the room when Green coughed up the keys to the kingdom.

But it was worth double-checking, even if it was a slow and cumbersome process. Armed with Gambaryan's new revelation, they determined that the Number13 account had sent the stolen bitcoins to Mt. Gox, the Japan-based bitcoin exchange that had since gone bankrupt. Gambaryan had to use a mutual legal assistance treaty (MLAT) procedure to get financial records from the Japanese bankruptcy trustee. Those records showed that the Mt. Gox money had cashed out to a Fidelity account registered to "Quantum Investments," a company that Bridges had amazingly registered in his own name, using his actual home address in a Maryland city between Baltimore and Washington, DC.

From there, the next part was easy. A subpoena to Fidelity took less than a day to come back, showing who had created the Quantum account—Shaun Bridges.

The Secret Service was notified that Bridges was under investigation and suspected of wrongdoing. The usual process would be for Bridges to be put on some kind of leave. Instead, on March 15, 2015, he resigned. To Haun and Gambaryan, that strongly suggested they had hit the target. Bridges was a second, bigger thief—and he thought himself the smarter one.

Haun brought in her boss, Assistant United States Attorney William Frentzen. He had supervised Haun on the Ripple Labs case, a related cryptocurrency. A 20-year veteran of the Department of Justice, Frentzen had also worked with Haun on organized crime cases.

"The hair stood up on the back of my neck," he recalled in an interview with Ars. "There’s two of them."

Bridges was offered a proffer session, and his lawyer said he wanted to cooperate. They flew out together to San Francisco to meet with Haun and her team in person. But Bridges wasn’t conciliatory or apologetic; he was arrogant and unrepentant.

"The missing link, you don't have," Bridges told Haun from across the conference table.

He thought the Mt. Gox records, showing the stolen bitcoins moving from Silk Road into his Quantum account, were impossible to get. And Bridges had even tried to make them impossible to get—his Baltimore team instituted a civil seizure proceeding against Mt. Gox, and Bridges attempted to go to Japan to collect the records himself.

"We would charge you and try you without those," Haun told him plainly. But there was more bad news for the corrupt agent—she and Gambaryan did have the exact records Bridges thought would be missing forever.

Usually, the dynamic in a proffer session is frank: "We’ve got you, don’t bullshit us," Haun said. “Yet he was untruthful. He thought he was the smartest guy in the room and no one else in the government would be able to ‘get it,’ to understand what he did."

Charges were filed against Force and Bridges, with Gambaryan’s name at the bottom, on March 30, 2015.

Arrests

Within a month, Bridges pleaded guilty. Weeks later on July 1, 2015, Force did, too. Bridges was ultimately sentenced to 71 months, while Force was given 78 months. Force is serving time in a federal prison near Louisville, Kentucky and is due to be released in 2020. Bridges is now behind bars at the Terre Haute Federal Correctional Institution, 70 miles west of Indianapolis, Indiana. He'll be a free man in 2021.

During their respective sentencing hearings, Force did not speak, but Bridges did.

"I knew when I turned in Carl Force that it would ultimately lead to me," Bridges told the court. "I mean, the person turning him in worked with him; they're obviously going to look at me. But I accept that. I don't diminish one bit of it here."

Bridges also said he wanted to "apologize to everybody" and acknowledged that he "accepts full responsibility" for his actions.

However, while the judge and everyone else (including Ars) believed that Bridges' story was effectively over, he was likely the only one in the room who knew that it wasn't.

Two days before Bridges was set to report to prison, Bridges asked the judge for permission to turn himself in a day early due to snowy weather conditions that could possibly impede the 10-hour drive from Baltimore to his assigned prison in New Hampshire. US District Judge Richard Seeborg granted this request.

Within hours, investigators suspected that Bridges wasn’t going to make the drive after all; instead, they anticipated he would try to flee the country. (Gambaryan declined to explain exactly how authorities figured this out.) Bridges was taken into custody for the second time, arrested at his home on January 28, 2016. Gambaryan and a team of about 20 agents surrounded the house in an affluent neighborhood outside Baltimore. The agents drew guns, and they ordered Bridges to open the door or they would break it down. Bridges opened the door.

In two bags, the former Secret Service agent was carrying ID documents, a notarized copy of his passport, a passport card, and corporate records for three offshore companies—in Nevis, Belize, and Mauritius. One of them had been created on October 28, 2015, well after pled guilty.

Despite his pleading guilty, Bridges has also filed an appeal in his case. It's an unusual move since Bridges, like most defendants who take a deal with prosecutors, waive their rights to an appeal.

Meanwhile, court documents unsealed in early July 2016 show that prosecutors suspect Bridges of additional thefts, including $700,000 that was seized from various Bitstamp accounts on Bridges' orders.

His lawyer, Davina Pujari, filed an unusual brief on August 8, 2016, saying that the arguments Bridges wanted her to make were "legally frivolous." She also asked the judge to allow her to be removed as Bridges' lawyer. (Pujari did not respond to requests for comment.)

Questions

Despite the mountain of evidence uncovered by Haun, Gambaryan, and others, two underlying questions remain unanswered: how much did Force and Bridges collaborate? And was anyone else from the Baltimore Task Force corrupt, too?

The answer to the first remains unclear. Richard Evans, an assistant United States attorney in the DOJ’s Public Integrity Section and one of the prosecutors present for Bridges’ December 2015 sentencing, said as much to the judge.

"We've not revealed any evidence that would indicate that [Force and Bridges were collaborating]," he said. "In a small task force when you've got corrupt agents, one would think they would possibly talk about that. But we’ve not recovered any evidence to suggest that. And all we’ve got is that they were operating in separate silos, doing it on their own."

It still isn’t completely clear whether or not Bridges and Force collaborated, if at all. The men were at least friendly and knew they had "offline" interest in Bitcoin; they texted each other about price increases.

"There’s nothing that I found that suggests they were working together, which is crazy," Gambaryan said.

This lingering mystery may never be solved for certain. But a condition of both of men's sentences is that they are forbidden from communicating with each other.

"The whole case made me sick from start to finish," Frentzen said. "These are people that we work with every day."

As to whether others on the Baltimore Task Force were involved in corrupt activities, it’s also hard to know for sure. But after months of investigation, no one else has been charged.

Homeland Security Investigations Special Agent Jared Der-Yeghiayan testified at trial that there was at least one other federal agent operating on the Silk Road, under the handle "Mr. Wonderful." Ulbricht’s own files show that another user named "alpacino," whom he believed to be from DEA, was leaking info to him. This could have been Force, or it might have been another agent.

George Frost, the Bitstamp lawyer who kicked off this whole saga, remains convinced there are more suspects at large.

"It looks like there are still people out there that are involved," he said.

Source:

http://cyberparse.co.uk/2016/08/17/stealing-bitcoins-with-badges-how-silk-roads-dirty-cops-got-caught/

I would absolutely love to see a film made about this story, as long as they were fair to Ross Ulbricht. With all the corruption involved in this case, the guy should be freed immediately and the investigation into other players halted! The government need to clean up their own backyard on this mess, and make sure nothing like this ever happens again. But they probably won't! It a travesty that a case like this was even prosecuted in the United States. If it can happen to him, it can happen to any of us!

Me too my friend, it could be the best bitcoin-related thriller lol

Congratulations @bitcoin-c! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

SteemitBoard and the Veterans on Steemit - The First Community Badge.

Congratulations @bitcoin-c! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!