A functional guide for discussing and evaluating blockchains

Part of why the discussion around emerging blockchain companies is so fraught with conflict is that the definition of “blockchain” and the ideas behind it are still somewhat murky. This realization came after hours of arguing with my team about whether or not certain projects could claim to be “a blockchain,” or if that title was misleading or dishonest. Over the course of that discussion it became clear that we were not all talking about the same thing. The engineers in the group saw blockchain as strictly a data structure, and not all of the things that blockchain enables. The well-versed but non-technical members of the team insisted that the technology doesn’t exist in a vacuum and we can’t remove the expected, if not altogether technically necessary implications. This conversation makes it clear that we don’t have a common language we can use when talking about new blockchain projects. In this post I try to get at the nuance that so many definitions miss. The following is a proposed framework for a critical discussion on new blockchains or blockchain projects. Through this critical lens we can differentiate between the two meanings we ascribe to blockchain, and evaluate the qualities of each.

The Gene

The Bitcoin white paper first describes a “chain of blocks,” and how that data is strung together, but it also describes the method by which that data is received, verified and written. Since then those two separate components have been conflated and the word blockchain used to describe both. This practice is similar to the way we use the word “gene.” Gene refers to our genetic makeup, the DNA coding that determines our traits. However, we also use “genes” colloquially to describe those traits and how we came to possess them. Likewise, “blockchain” describes both the data structure like the DNA, as well as the network that leads to the data being written like the genes. I propose that we reserve the question of “blockchain or not,” for the data structure and break down the components of the “blockchain network,” individually.

Technical DNA

Blockchain is a data structure, or a particular method of storing information. It consists of a growing chain of transactions with each new ‘block,’ a finite grouping of transactions, referencing the previous block by way of a cryptographic hash. The blockchain is a ledger of transactions, each cryptographically signed ensuring simple validation of the entire history and preventing tampering. As the technology evolves the word “blockchain,” is being applied to structures that are not exclusively a chain of blocks, but is now is used to refer to other structures that store collections of transactions.

Network Genes

When we discuss blockchain as a network, the most common traits are those originally described in the Bitcoin white paper. In order to enable peer-to-peer transactions the Bitcoin white paper describes a network of nodes, each with a complete copy of the ledger, recording and arriving at consensus on each new block of transactions. The variables we use when evaluating blockchain networks are; distribution, openness, decentralization, and trustlessness. These traits are distinctive, but linked, each impacting the value of the others.

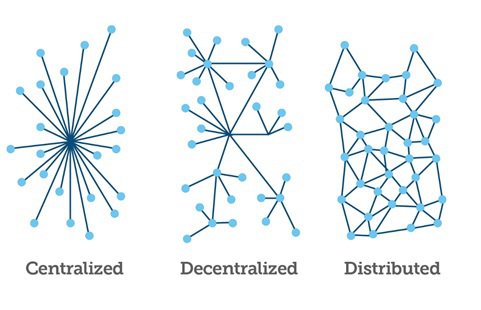

The lowest hurdle for evaluating a blockchain is the question of whether or not it is distributed. Distributed means that an entire copy of the ledger is held on each node and that there is more than one node in the network. There are varying measures as to what degree a network is distributed — how many nodes are present, are the nodes related to one another, and how geographically dispersed the nodes are. The more a ledger is distributed, the more difficult it becomes for bad actors to corrupt the network. From there the remaining variables can be examined by separating blockchain networks into two buckets, permissioned and open.

Permissioned

Permissioned blockchains are also called closed or private. Though they are typically distributed, the nodes that contribute to the blockchain are controlled by the organization that implemented or manages that blockchain. Permissioned blockchains are, what I will refer to as, quasi-decentralized, though they do not necessarily need to be. If the system uses some kind of consensus protocol and each of the distributed nodes has equal authority then the system appears decentralized. However, because the nodes are all granted authority by a central party, they cannot be truly decentralized in the way that open blockchains are. Consensus here is technically decentralized, but is the privilege of only the chosen validators. By staying in this decentralized middle-ground they are not as vulnerable to bad actors adding nodes to their network and causing harm, on the other hand, limiting the number of nodes puts increased value on the input of each making the network vulnerable.

Along that vein, permissioned blockchains are not “trustless,” in the way we expect open blockchains to be because there is an inherent requirement that members of the network trust the system gatekeeper. In the case of internal company blockchains for instance, this isn’t a problem because the company has no incentive to lie to itself and trustlessness isn’t a priority. Private or permissioned blockchains are gaining popularity as easy to use, more secure systems. Products such as BigchainDB, Hyperledger, Stellar and Dragonchain are all examples of permissioned blockchain based tools.

When evaluating permissioned blockchains it is useful to begin with several questions. By whom or by what method are permissioned nodes chosen? How many permissioned nodes exist in the network? To what degree are those permissioned nodes related? Are there economic incentives to prevent adversarial model, collusion etc.? These answers will lead to an understanding of to what degree the blockchain in question is distributed and quasi-decentralized.

Open

Open blockchains operate similarly, but permission isn’t necessary to become a node. This means that open blockchains are truly decentralized, because even if there was an authority that originally launched the project, the community has the authority to accept or reject transactions or changes. The argument could be made that some open blockchains are more neutral than others, depending on the composition of the network. Blockchains operating with fewer nodes can be considered less decentralized because the number of bad actor nodes required to overtake the system is smaller than blockchains operating with many, well-dispersed, unrelated nodes. That said, typically open blockchains are difficult to overtake in a way that would be economically feasible for the taker. With open blockchains users are not required to submit to a central authority deciding the validity of any transaction. Instead the network is structured such that each member is incentivised to behave within the rules and contribute to its continued existence. This means that open blockchains, with proper incentives and adoption, can enable trustlessness and peer-to-peer transactions. The principle of trustlessness was core to the Bitcoin whitepaper and the two are squarely linked in the wider social discussion of blockchain. Bitcoin, Ethereum and most other well-known, frequently-discussed blockchains are open.

When evaluating open blockchains it is useful to begin with several questions. How many nodes are operating on the network? How dispersed are those nodes? What qualifications does one have to meet to become a node? What is the barrier of entry to becoming a node; technological, economic or otherwise? Does any central authority have to approve new nodes?

How To Speak Blockchain

As we use the word now, Blockchain means everything and nothing at all. This leads to confused clients, unclear project descriptions and, in extreme cases, SEC subpoenas. Here I have established the beginnings of a critical framework for discussing the merits of a blockchain project. As with any innovative technology these variables will change over time, but having a standard rubric to guide the discussion of blockchain projects is valuable. Having a common language allows us to examine projects critically in a productive way. Going forward I will be using this archetype in my critical analysis of projects, and will continue to refine it based on changes to the landscape.

If you have suggestions, comments or anything you’d like to add — drop it in the comments below, contact me on twitter @benson4america or by email at [email protected]

Coins mentioned in post: