This is where it started.

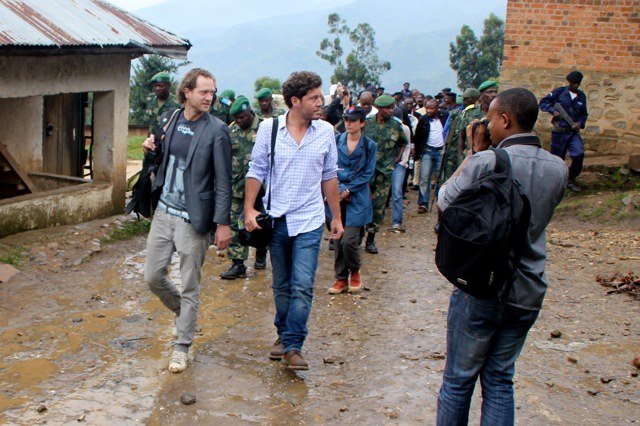

February 2013, in the town of Nyabibwe, Kalehe territory of the South Kivu province - Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

There are a handful of misconstrued reasons for foreigners to visit this place:

#1 procuring tin, tantalum or tungsten ores, which have come to be known as conflict minerals

#2 exposing the issue of conflict minerals

#3 riding the conflict minerals wave to generate new opportunities

#4 sorting out the mess caused by (1), (2) and (3)

#5 conflict tourism

I originally came for #5. It was a coincidence. I had a bit of time on my hands and those guys needed someone to join the so-called Conflict-Free Tin Initiative (CFTI) delegation on a visit to what promised to be the first verifiably conflict-free tin supply chain originating from Eastern DRC.

There was an opportunity for me to travel to places I never really thought could be on anyone's bucket list. But it came with what already felt like sobering responsibility.

Conflict minerals

War-torn Congo's misery had been so efficiently pegged to its mineral wealth by a new breed of supply chain activists that in 2010 a conflict minerals provision (section 1502) was added to the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. In 2012 the US Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) turned that provision into a fairly well-crafted piece of regulation incentivising US-listed companies to disclose their conflict minerals footprint.

As tempting as it may be, there is no need to get political to understand the DRC conflict minerals issue. It is of course about money. To motivate troops, bribe influent officials, buy weapons and secure local community adhesion (often through fear, terror), a warlord needs money. US dollars that is.

Contemporary with the first Congo war, in the second half of the 1990s, was the price rise of certain materials crucial to the innovation bubble fuelled by the ICT revolution. Among those were - you guessed it - tin, tantalum and tungsten. In Nyabibwe, as in many towns around Lake Kivu - particularly in the geologic scandal that is Congo, tin literally oozes from the ground. Not that it is an easy work to mine it (I will get to that later).

For familiar reference think of gold, incidentally the fourth conflict mineral: getting gold to a stage where it can be traded requires limited investment, which makes gold mining a tempting activity for anyone encountering deposits in their backyard. The same is not true of uranium, for example.

So in Nyabibwe, throughout the Congo wars, controlling the tin ore (cassiterite) trade yielded tremendous revenues for local terror groups, most of which turned into the worst form of businessmen: greedy, unchecked, unaccountable, exerting power through extreme intimidation, and violence ranging from forced child labour to mass rapes and arbitrary killings.

As I humbly reached Nyabibwe, swayed by such a history, security had been reestablished. I did not immediately believe that - having travelled as part of a heavily guarded convoy comprising representatives from all corners of the noble mineral supply chain international stakeholdership, but it is obvious in hindsight that my first trip to Congo occurred at the twilight of the World's worst war.

My mission was to briefly evaluate the local mineral supply chain, from Nyabibwe mine sites to export, and assess its circumstances and conflict-free status against the de-facto international standard for this type of assignment, a standard jointly developed by all supply chain stakeholders under the patronage of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

In the world of compliance, there is no shortcut to defining right and wrong, so the following summary is contestable: US-listed electronics manufacturers may only declare their product (or even their procurement practices) as conflict-free if they have conducted due diligence on their supply chain to a satisfactory level. And the SEC recommends the above OECD framework to conduct such an investigation. If a company uses tin, tantalum, tungsten or gold in the making of its products, it must identify the origin of those materials. And if that determination leads to Central Africa, reasonable efforts must be made to track materials all the way back to conflict-free mines.

Think about it. Think about international companies' response to such a legislation. Imagine where that distant issue ranks in the list of Apple's board-level priorities. Then again think of how fundamental brand reputation is to charging you $1,000 for a smartphone, and remember how hard the sweatshop controversy had hit Nike.

Just as Nike initially made the case that it did not itself hire cheap labour, the electronics industry was prompt to argue that conflict minerals supply chains are complex, and that end-users cannot control or even start to understand upstream practices.

Unlike the Nike scandal, the conflict minerals rule targeted an entire industry. So in fairly standard fashion, the industry mutualised efforts through alliances such as the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC) and the Global e-Sustainability Initiative (GeSi). They then identified that the mineral supply chain gets much simpler at the level of smelters (pinch point). Therefore, compliance / corporate sustainability money was spent on (1) identifying which smelters are in your supply chain and (2) joint-auditing of smelters via the EICC-championed Conflict-Free Sourcing Initiative (CFSI).

Unintended consequences

Smelting is a low-margin business, for which steady volumes matter as much as a a consistent pricing formula. Being directly accused of sponsoring the conflict, and presented with downstream requests for additional transparency efforts when procuring from Central Africa, many smelters simply walked away from that deal. Resistance of companies and industry groups to the costs of diligence and reporting led to an embargo of minerals from the DRC. In fact, even the DRC government itself temporarily made conflict minerals exports illegal until such time when a mechanism can be implemented to ensure that in-country supply chains are not linked to non-state armed groups.

But for the people of Nyabibwe, the suspension of trade also meant that their largest source of income had dried out.

In the Kivus, artisanal and small-scale mining had become essential to local livelihoods. As such, by 2012, while trade restrictions undoubtedly contributed to local scrutiny and deterred certain armed groups, international conflict minerals pressure and the Obama law started to be blamed locally for burying local communities into poverty.

Turning our back on the issue, by declining to buy from the affected region, is the worst possible response to conflict minerals. It does nothing to promote transparency and accountability. As pseudo-responsible buyers walk away, the field opens up to non-responsible operators. And as market access constraints affect local development outcomes and revenue generation, securing long-term peace and stability becomes more challenging.

Fortunately, for various reasons ranging from the relative value of their brand, position in the supply chain, and even the personality of executive managers, certain companies expressed an interest in understanding the most distant parts of their supply chain.

That is what this visit was about.

[tbc]

Super post

Congratulations @benclair! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard!

Participate in the SteemitBoard World Cup Contest!

Collect World Cup badges and win free SBD

Support the Gold Sponsors of the contest: @good-karma and @lukestokes

Congratulations @benclair! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!