The architecture of Africa, like other aspects of the culture of Africa, is exceptionally diverse. Throughout the history of Africa, Africans have had their own architectural traditions. In some cases, broader styles can be identified, such as the Sahelian architecture of an area of West Africa. One common theme in much traditional African architecture is the use of fractal scaling: small parts of the structure tend to look similar to larger parts, such as a circular village made of circular houses.

The history of African architecture

In the 1940s and ’50s, experiments in architecture and urban planning were carried out across the African continent, but mostly by Western architects such as Le Corbusier and Aldo van Eyck, who were particularly influential in the creation of mass housing schemes in Morocco and Algeria.

When African nations started gaining independence, between the 1950s and ’80s, colonizers used “International Style” to show their good intentions of leading colonies toward the future. This style is a modernist approach developed in Europe and America in the 1920s and ’30s and is characterized by the use of concrete, steel and minimal ornamentation.

In May 1981, the new African Union of Architects began uniting architects of all races, religions and nationalities across the continent. Other national architect associations and action networks — such as Adventurers in Diaspora, Casamémoire, Doual’art and ArchiAfrika — were created to stimulate the debate on the quality of the built environment and the value of Africa’s artistic and architectural heritage.

With the fast pace of economic growth in Africa from 2000 to 2008, these organizations kept a concerned eye on valuable architectural assets in African cities — the historical buildings in the city center of Dar es Salaam, for example, and the National Museum in Ghana. Architects and academics alike within the continent began paying more attention to the buildings in their countries.

“Up to now, important projects on the continent were designed by foreign architects,” says Jean Charles Tall, architect and founder of the College Universitair d’Architecture de Dakar.

“When you go to a bookshop, even in Africa,” he continues, “all the books written on African architecture are written by people from outside of the continent, with an anthropologist perspective or for tourists.”

So Tall is urging further discussion and research about architecture across Africa. Forums of discussion between practicing architects, students and academics, he says, will allow this generation to further voice its own opinion and move African architecture onto the global stage.

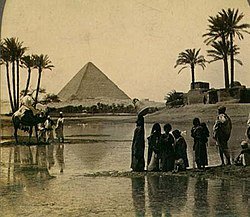

Pyramid of Giza ( Egypt 🇪🇬)

African architecture uses a wide range of materials. One finds structures in thatch, stick/wood, mud, mudbrick, rammed earth, and stone, with the preference for materials varying by region: North Africa for stone and rammed earth, Horn of Africa for drystone and mortar, West Africa for mud/adobe, Central Africa for thatch/wood and more perishable materials, Southeast and Southern Africa for stone and thatch/wood.

-Domicile (beehive)

-Cone on cylinder

-Cone on poles and mud cylinder

-Gabled roofed

-Pyramidal cone

-Rectangle with roof rounded and sloping at ends

-Square

-Dome or flat roof on clay box

-Quadrangular, surrounding an open courtyard

-Cone on

Early architecture

Probably the most famous class of structures in all Africa, the pyramids of Egypt remain one of the world's greatest early architectural achievements, if limited in practical scope and originating from a purely funerary context. Egyptian architectural traditions also saw the rise of vast temple complexes and buildings.

Little is known of ancient architecture south and west of the Sahara. Harder to date are the monoliths around the Cross River, which has geometric or human designs. The vast number of Senegambian stone circles also evidence an emerging architecture.

-African Architecture: 21st century “Afritecture”-

African Architecture: 21st century “Afritecture”. A new book and exhibition, which celebrate innovative approaches in “aesthetically pleasing” African architecture – designed with local conditions and requirements in mind, and suited to the needs of its users and climatically attuned to its location. Is this where contemporary African architecture stands in the early 21st century? Juliet Highet reports

In addition to the use of the latest technology, the projects in question, were developed using local materials rather than imported, and revive abandoned building traditions. By taking on board environmental and social aspects, the architects have promoted sustainable approaches and found solutions to some of the Africa’s most demanding design challenges.

Many regions of Africa are enjoying economic growth, accompanied by brisk building activity. Rapid urban growth is decidedly altering the continent, especially the breakneck, unplanned expansion of large cities in an unending sprawl, creating slums characterised by barely endurable living conditions.

The pull of these horizontal megacities of people from rural areas is unrelenting, but the inherent problems are rarely addressed by the politicians, building developers and investors in whose hands ‘new towns’ are being developed, paying scant if any attention to the sociological perspective of their architecture.

In 2008, a soulless new Angolan town called Kilamba, covering 5,000ha, 30 kms outside the capital Luanda, was erected by Chinese investors and workers. With its identical high-rises, surrounded by barren land devoid of anything natural such as a tree, it is an archetypal example of a culturally alien approach, implemented with no regard for actual needs or indigenous traditions. Furthermore, ironically, it was built to house a hitherto non-existent middle class.

This controversial power structure for new buildings, of government and urban planners and through private investment, pays little or no attention to small-scale but significant connections that people negotiate on a daily basis to make a living and survive in an urban context. These include fields and gardens, streets and markets, entertainment venues, mosques and churches.

The official vision of the urban future totally overlooks and excludes the vast majority of those surviving in the harsh realities of the existing and ever expanding informal megacities. And, as we have seen at Kigala, foreign real estate investors construct huge gated communities. Other alien satellite cities include Takoradi, Appolonia and Kilamba in Ghana, Tatu City and Koza City in Kenya, and Cité du Fleuve in Kinshasa, DRCongo, to name just a few.

Aspects of traditional African architecture, some of which can be traced back thousands of years, such as building with clay or adobe, are in danger of disappearing, displaced by imported building materials and technologies. These require considerable levels of fossil energy and cannot be produced by local workers. After completion, such buildings dictate a continuing reliance on further energy-guzzling technologies, such as air-conditioning.

But there are important developments and innovative approaches in today’s African architecture, some featured in this exhibition and book, which could serve as pioneering prototypes. In most cases, finance for the featured projects often comes from aid organisations and private contributions, but in this case, all were achieved with direct support and participation of the local communities, with their architects developing appropriate designs through a precise knowledge of local conditions and requirements. Not least, they are all aesthetically pleasing. What we are currently seeing is a genuine emergence of an African vernacular contemporary architecture, suited to the needs of its users.

Nigerian architect Okwui Enwezor gives as an important example of a blend between traditional architecture and contemporary sculpture the work of Austrian Suzanne Wenger and her Nigerian colleagues, creating the sacred groves for the Yoruba pantheon at Oshogbo, in clay reinforced with cement. He recalls his grandmother’s clay house: “We lived in the city in a modern building. But my grandmother preferred to live in a simple adobe home. During sweltering periods, her house remained cool. In terms of its structure and form, it is the type that Westerners would disparagingly call a ‘hut.’ With its peaked thatched roof, which sloped down to provide shade, and its low, thick adobe walls, it solved the science of climate control and ecological conservation.”

Around 800 years ago, the first kingdom in southern Africa was located at Mapungubwe, on the borders of Botswana and Zimbabwe. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and nature reserve, its recently built visitor and administration areas, called the Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre, incorporates the natural contours of the landscape. South African architect Peter Rich created a group of vaulted pavilions using centuries-old building techniques and sustainable construction. Multiple layers of flat earthenware bricks were used, because of their high compressive strength, appropriate for vaults and arches. The bricks were made with hand presses, operated by 60 local labourers, who were trained in brick manufacturing techniques. Air-conditioning was completely omitted, owing to the thermal storage capacities of the bricks.

The vaulted buildings are a brilliant re-interpretation of traditional ‘huts’, whose exteriors are covered in layers of local stone, so that they give the impression that they have grown directly out of the landscape.

The Central Market at Koudougou, Burkina Faso, is a massive complex constructed from bricks made of pressed earth. It too was produced by local companies and workers in the ancient Nubian style of vaulted ceilings and large round-arched arcades. It won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2007. The Central Market is largely operated by women, can be locked at night and is considered key to the economic advancement of the region, which is some distance from the capital Ougadougou. The concept behind this is to foster financial stability in under-developed mid-sized cities, and prevent excessive population drain in rural areas. One of the stipulations for financing was that part of the profits of the market should be invested in new social building projects, such as schools and bus stations.

In Ethiopia a two-story prototype also using vault construction was developed by the Ethiopian Institute of Architecture, Building, Construction & City Development (EiABC), as an alternative building model for Ethiopian cities. Subsequently four different sustainable units were created including Urban, Rural & Emerging City Units. Two different construction techniques were used – rammed earth and loam brick. The roof was sealed with a water-resistant mortar made of mud, salt and the fermented juice of the cactus pear, an old and almost forgotten technique reimported from Mexico by an Ethiopian artist.

At the Sustainable Emerging City Unit (SECU) the support structure is made of prefabricated straw boards. Traditionally straw has been used as a cost-effective building material with good insulation properties, and it is easily available in amounts in Ethiopia, in contrast to wood. The boards are coated with recycled cardboard packaging.

Ethiopia is starting to surmount many architectural problems. Up till now, the Ministry for Urban Development & Building has implemented only expensive, imported Western materials and technologies, creating serious economic trouble. Around 80% of the country’s enormous trade deficit can be attributed to the import of cement, steel, glass and construction machinery. The local lack of familiarity with using such materials and techniques results in serious deficiencies in building quality, and a feeling of alienation against the Western – and now outdated – Modernist style of architecture.

These problems are common all over the continent, and are beginning to be solved by innovative approaches in architectural education. The same institute, EiABC, which is currently training 3,000 students in architecture, seeks to integrate valuable international technological standards non-intrusively with local methods and materials. For instance natural products like bamboo, mud and straw are processed using new locally developed technologies.

In South Africa architectural education for everyone came late, but with the advent of the democratic government in 1994, dramatic changes began taking effect. A new Council of the Built Environment (SACAP) has ensured two-tier degree programmes in new architectural schools, and universities of technology offering professional degrees.

But due to financial constraints, many students have not been able to complete their courses. So a solution has been found whereby they work for a registered professional architect, while continuing their studies via the internet. All that is required is a laptop and good internet connection. Within two days of announcing this new course, it had received over 80 hits on Facebook.

Homeward bound

This growth in contemporary African architecture has led several distinguished African architects who have lived and worked overseas to return to their home countries. The most well-known is Ghanaian Joe Osae-Addo, 42, who moved back to Accra in 2004.

Although Osae-Addo had run a thriving architectural practice in Los Angeles, he hoped to better align himself with his beliefs on sustainability, and Ghana was the place to do so.

At that time, most urban homes in Accra, the capital of a former British colony, were concrete-block houses made with imported English Portland cement. Dissatisfied with this drab approach to living, Osae-Addo was determined to find ways to build his home with locally sourced materials.

“I wanted to explore ideas of light, cross-ventilation and lightness of structure,” he says. As a result, Osae-Addo designed his home to stand 3 feet off the ground on a wooden deck, so that under-floor breezes would cool the space naturally. He also incorporated slatted-wood screens and floor-to-ceiling jalousie windows for cross-ventilation.

“Interstitial spaces and landscape are what define tropical architecture,” he says. “It is not about edifice but rather harnessing the elements — trees, wind, sun and water — to create harmony, not the perfection that modernism craves so much.”

Osae-Addo applied these sustainable building principles to other projects, too, such as the Oguaa Football for Hope Centre in Cape Coast, Ghana, which was constructed with reclaimed scaffolding, donated shipping containers, and indigenous bamboo and adobe bricks. “Africa is not just a place of inspiration,” he says, “but a place to live, grow and create.”

Early European colonies developed around the West African coast, building large forts, as can be seen at Elmina Castle, Cape Coast Castle, Christiansborg, Fort Jesus and elsewhere. These were usually plain, with little ornament, but showing more internal creativity at Dixcove Fort. Other embellishments were gradually accreted, with the style inspiring later buildings such as Lamu Fort and the Stone Palace of Kumasi.

By the late 19th century, most buildings reflected the fashionable European eclecticism and pastisched Mediterranean, or even Northern European, styles. Examples of colonial towns from this era survive at Saint-Louis, Senegal, Grand-Bassam, Swakopmund in Namibia, Cape Town in South Africa, Luanda in Angola and elsewhere. A few buildings were pre-fabricated in Europe and shipped over for erection. This European tradition continued well into the 20th century with the construction of European-style manor houses, such as Shiwa Ng'andu in what is now Zambia, or the Boer homesteads in South Africa, and with many town buildings.

The revival of interest in traditional styles can be traced to Cairo in the early 19th century. This had spread to Algiers and Morocco by the early 20th century, from which time colonial buildings across the continent began to pastiche elements of traditional African architecture, the Jamia Mosque in Nairobi being a typical example. In some cases, architects attempted to mix local and European styles, such as at Bagamoyo.

The effect of modern architecture began to be felt in the 1920s and 1930s. Le Corbusier designed several unbuilt schemes for Algeria, including ones for Nemours and for the reconstruction of Algiers. Elsewhere, Steffen Ahrens was active in South Africa, and Ernst May in Nairobi and Mombasa.

The Italian futurists saw Asmara as an opportunity to build their designs. Planned villages were constructed in Libya and Italian East Africa, including the new town of Tripoli, all utilising modern designs.

After 1945, Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew extended their work on British schools into Ghana, and also designed the University of Ibadan. The reconstruction of Algiers offered more opportunities, with Algiers Cathedral, and universities by Oscar Niemeyer, Kenzo Tange, Zwiefel and Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. But modern architecture in this sense largely remained the preserve of European architects until the 1960s, one notable exception being Le Groupe Transvaal in South Africa, who built homes inspired by Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier.

A number of new cities were built following the end of colonialism, while others were greatly expanded. Perhaps the best known example is that of Abidjan, where the majority of buildings were still designed by high-profile non-African architects. In Yamoussoukro, the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro is an example of a desire for monumentality in these new cities, but Arch 22 in the old Gambian capital of Banjul displays the same bravado.

Experimental designs have also appeared, most notably the Eastgate Centre, Harare in Zimbabwe. With an advanced form of natural air-conditioning, this building was designed to respond precisely to Harare's climate and needs, rather than import less suitable designs. Neo-vernacular architecture continues, for instance with the Great Mosque of Nioro or New Gourna.

Other notable structures of recent years have been some of the world's largest dams. The Aswan High Dam and Akosombo Dam hold back the world's largest reservoirs. In recent years, there has also been renewed bridge building in many nations, while the Trans-Gabon Railway is perhaps the last of the great railways to be constructed.

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina at Shatby, Egypt—a large airy spacious regional public library, built overlooking the Mediterranean—completed in 2001 and designed by Snøhetta, in association with Hamza Associates of Cairo, is a good example of a modern granite-cladding construction. A commemoration of the Library of Alexandria, once the largest library in the world but destroyed in antiquity, the new Library's architecture is ultramodern and very non-traditional.

The new African architect

“The next generation of architects is our future,” Osae-Addo says. “They have all the tools and technologies at their disposal and a growing awareness of their own roots. The old guard must recognize this and nurture and support them.

Atepa shares Osae-Addo’s focus on the next generation, believing that all Africans, no matter where they live, should participate in the development of African architecture.

“The wealth of tomorrow is in Africa,” he wrote in a June 2008 interview with the African art blog Unseen Art Scene. ”I received everything from Africa. So I must give something back. . . . Africa is the cradle of art. If African architects succeed one day in making the symbiosis between African art and modern architecture, the result will be magnificent.”

References

^ Eglash, Ron (1999). African Fractals Modern Computing and Indigenous Design. ISBN 978-0-8135-2613-3.

^ Davidson, Basil (1995). Africa in History. p. 50. ISBN 0-684-82667-4.

^ Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-313-32501-4.

^ Bietak, Manfred. The C-Group culture and the Pan Grave culture Archived May 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.. Cairo: Austrian Archaeological Institute

^ Kendall, Timothy. The 25th Dynasty Archived April 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.. Nubia Museum Archived June 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.: Aswan

^ Kendall, Timothy. The Meroitic State: Nubia as a Hellenistic African State. 300 B.C.-350 AD Archived April 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.. Nubia Museum Archived June 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.:Aswan

^ Prof. James Giblin, Department of History, The University of Iowa. Issues in African History Archived April 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

^ Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (2005). The History of African Cities South of the Sahara From the Origins to Colonization. Markus Wiener Pub. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

^ "Archaeology and the prehistoric origins of the Ghana empire". The Journal of African History. 21: 457. doi:10.1017/S0021853700018685.

^ "Coping with uncertainty: Neolithic life in the Dhar Tichitt-Walata, Mauritania, (ca. 4000–2300 BP)". Comptes Rendus Geoscience. 341: 703–712. doi:10.1016/j.crte.2009.04.005.

Michele Koh Morollo

Congratulations @henrilex12! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board of Honor

Congratulations @henrilex12! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!