In the attic of a garage near Powderhorn Park in Minneapolis, MN, United States. 10:52 GMT, 12 Jan - 17 Jan 19:25 GMT, 2018.

Here, I'll explore how the aesthetic philosophy of Darren Allen described in his Peanut History of Art (specifically how his idea of panjectivism) resonates with my posts on Steemit thus far.

Panjectivity (n): art of a particular style, typically soft-edged, which represents pre-objective and pre-subjective awareness (i.e., an awareness [both of] THINGS that are 'out there' and THOUGHTS and FEELINGS which are 'in here'; gives DEEP MEANING and HILARIOUS NUDITY to mere facts, to [mere me]; synonym of QUALITY.

- I'm an anarchist with "an inveterate fondness for dogs, riots, and 'riot dogs.'"

- I described why I became an anarchist as a response (both political and visceral) to the final passages of T.H. White's The Once and Future King. My instant sense of kinship with the spirit of those words, and the world they propose, and which I later summarize as a set of principles—an aesthetic—underlying the view of the world this novel proposes: one without borders, with what I will now describe as municipalities maintaining unity with their neighbors according to the principals of democratic confederalism (which, on or around 15 Dec 2017, I amusingly misspelled in an imaginary variant: "confederationalist"). Of these societies, I briefly outline those existing today, though I must admit my post fails (as have my further offerings) to give the Democratic Federation of Northern Syrian the treatment (and praise) I believe their efforts deserve.

- Avoiding the question my previous post demands—that being, an explanation of why a work of literature should have so completely changed my politics, and accordingly determined my own worldview; i.e., a theory of how what I will call for now "an aesthetic experience" may change one's entire identity—I instead turned the writer whom I might call my patron saint. Although I must admit I would have trouble choosing between Bolaño, Henry Miller, and Italo Calvino, I knew from my ruminations on the aforementioned phenomenon that even diversion into Bolaño would at least introduce personal reports of "aesthetic experiences" I'll soon discuss.

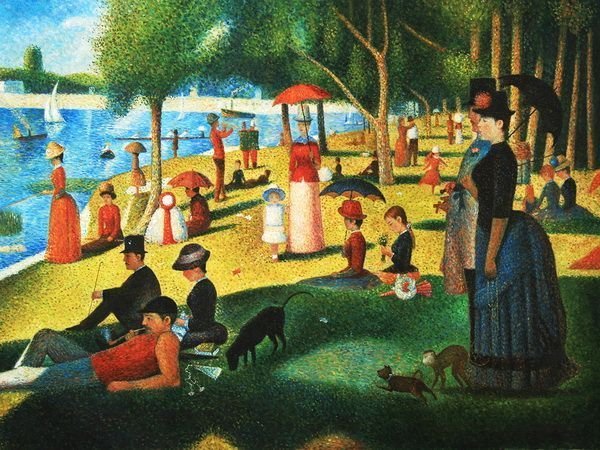

- Still, I knew I couldn't avoid for long that question of how aesthetics—here, works of art and literature can provoke such a visceral response that, for example, viewing Goerges Seurat's "Un dimanche à la Grande Jatte" (1886) forced me to take a seat on the bench of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2013—can have such an influence on a person that they can provoke such potent responses from us, according to our taste.

(Source) Yet I can't say I explored that topic directly, or at least not initially. Deciding to error on the side of caution, and I first offered definitions of "aesthetics," both traditional and contemporary, which I feel we may reasonably synthesize into the following—and, please, take the block quote as scare quotes:

Aesthetics (n): The underlying principles of how the subject senses, perceives, thinks about, feels toward, and gains knowledge about the world in which the subject lives.

Following a short discussion of how the definitions I have just synthesized may help to explain the effect of literature upon my consciousness to such an extent that it provided much of the substance for my the substance for my introductory post, I could only conclude in frustration, knowing that I hadn't yet reached any further understanding of how aesthetics becomes a factor in determining ideology—let alone a proposal for any kind of 'aesthetic program' to promote the cultural transformation so that we may enjoy a society not just without borders, but one in which 'Might'—whether military, capital, or of any other kind—provides nothing like 'Right,' let alone any protection from justice.

Cracking the Egg Further exploring the relationship between aesthetic and ideology, I turn to Darren Allen, and the tension between panjectivism, objectivism, and subjectivism throughout the history of art, and how these tensions reflect the tensions of historic ideologies dominant during the time of these works' production, which Allen covers with impressive attention to detail in his Peanut History of Art.

Profile picture of Darren Allen on Twitter @expressiveegg (Source) Beginning with a discussion of prehistoric art, Allen writes:

The earliest artistic images were expressions of panjectivity ... Objects were not perceived as hard, isolated forms, but as fluid expressions of a felt reality in which the context ‘out there’ blended with the consciousness of the observer ‘in here,’ and from which both the objective time and space and the subjective thoughts and feelings of the self emerged ... Like everything else [the subject of an artwork remained representative of] itself, but it was other; man, beast and unfathomable living weirdness. This otherness was not apprehended imaginatively or speculatively, as a whimsical illusion, or sentimentally, as a totemic symbol, but erupting in the heart, with catastrophic gaiety, represented, as it is, with free vibrating strokes, a vivid inner life sweeping across the fields of darkness. The power and character of the bull, like that of any animal, existed within, in this inner abyss, of the still, dark mind which primal people sought to embrace, and without, in the still, dark caves that primal people sought to be embraced by .... These earliest images are multi-dimensional, integrated into a complete sensory experience ... [the subjects of art] live, and through the conscious experience of this life, they communicate psychologically transcendent realities to the reverent beholder; the sense that the living quality of the animal is a function of consciousness, that I am that .... The sense that reality lives—that, miraculously, it has the quality of a living creature—suffuses all primal art. The universe was consciously felt and conceived as an organism; fundamentally benevolent, productive, mysterious and impenetrable to the rational mind .... And yet. The archeological record is surprisingly bare of truly ancient art. John Zerzan suggests, plausibly, that art was unnecessary for early people. Utterly blended as they were with the panjective actuality of reality, [early humanity] had no need for any kind of objectifying, sense-separating, representational activity; the cave paintings and mystic figurines we admire for their virtuosity actually represent the first steps in a degradation of conscious life, the beginning of superstition, whereby images and myths, controlled by a central shaman figure, stood in for a lived experience that was beginning to slip away.

(All of Allen's original emphases and links have been retained.)

Above, we see Allen describing the features and context of his panjective artworks in greater detail. Worth noting, I think, is the hypothesis Allen mentions of Zerzan, in which the representational ability of art served no useful purpose for pre-civilized humanity. Should you feel like following this hypothesis in greater detail, and discovering what other changes to the human lifestyle the advent of 'civilization' imposed, I recommend Fredy Perlman's 1983 Against His-story, Against Leviathan (full text available through link). While I don't expect to spend much time writing about anarcho-primitivism, my planned trajectory for this series of posts also demands I call attention to Allen's description of what I'll call 'prehistoric humanity's experience of reality as a living creature alive of its own accord,' an idea to which I plan to return in earnest with my later posts, and Perlman has absolutely informed my own worldview, so I will mention her simply in case it might spike your interest to study a brilliant scholar.

(Source) More relevant to any description of definition of panjectivism, an appendix to Allen's "Peanut History of Art," "What Is Real?", offers us some further context on the quote above:

Only that which is not self can truthfully respond to unselfish expressions of reality and can recognise the elusive, ineffable or mysterious component of the message as somehow right, truthful, good or beautiful. Such expressions, or answers—both selfish and unselfish—are presented to us in philosophy, literature, music, ordinary conversation or communication and—the medium under investigation here—art .... Artistic truth is neither objective nor subjective—it is panjective.

Perhaps we should keep in mind, then, that we may identify what I have called above the "experience of reality as a living creature alive of its own accord," as a sensation available through panjective artwork, according to a given work's ability which 'provokes a response' from what Allen calls "that which is not self." As Allen describes it in his "I am not my self!":

My conscious experience—I—blends into, but, ultimately, precedes this self—me. It is possible to be conscious of thought (to observe the screen of the mind), it is possible to be conscious of emotion (to feel it in the body) and it is possible to be conscious of self-created stuff (to ‘pull back’ from the isolating, naming mind and experience the whole moment).

Therefore, we can arrive at the following synthesis of Allen's panjectivity, from the quotes and the texts of images above. (Once again, please take these block quotes as scare quotes.)

Panjectivity (n): A characteristic of or category for works of art typified in a soft-edged, pre-objective and pre-subjective awareness—i.e., an awareness of both internal phenomena like thoughts and feelings, and external phenomena such as the events represented in an artwork—through which the viewer of a panjective work of art may forget or involuntarily "'pull back'" from their "naming [evaluative] mind," and thereby experience reality as a living creature alive of its own accord, providing the artwork with either or both a sense of deep meaning or a sense of amusement at the revelation of what Darren Allen calls "a hilarious nudity to mere facts."

With that established, we can move on to Allen's description of how, over the of humanity's development into what the Anglophone world calls 'the Classical Era,' the panjectivity that suffuses the art of prehistoric humanity began to decline into subjectivism, with corresponding developments in the structure of society, and which Allen, writes, remain "inimical to unselfish panjective expressions of atistic truth."

‘Civilised’ art, therefore, was initially subordinated to the selfish subjective emotions of fear and desire. As ‘civilisation’ evolved the emphasis changed to equally selfish objective ideas of perfection and accuracy .... By the time we reach Greece and Rome the purpose of art is to habituate us to an entirely symbolic reality[:] the illusory subjective-objective matrix which has dominated all cultural output since the dawn of recorded time.

However, despite the lost panjectivism in aesthetics, Allen confronts the tensions between subjectivism and objectivism throughout the 'Classical Era.' Whereas, he writes, "Panjective pre-modern medieval art of the East and West ... is often overflowing with character, sweetness and an intimate sense of the actual living quality of ‘inanimate’ matter. There is a felt sensitivity to the character of animals"; however, "as objectivity returns to art and the humanist renaissance strikes, begins once more to fade." As Allen explains of the artistic techniques developed during Europe's Renaissance:

With the rediscovery of so-called ‘objective’ science came the discovery of so-called ‘objective’ perspective, the great innovation of the late middle ages which heralded the birth, in art, of the modern age. Once again though we have what claims to be an objective idea, technique or experience but which, actually, still privileges the self and its society .... Perspectival pictures, first of all, only represent the mind-made ‘civilised’ world—there is no perspective in nature, because there are no straight lines. Secondly, these straight lines force the viewer, and the painter, to subordinate the whole of the image to the concentrated [vanishing] point of it. The lines of the walls, roads and tiles are not to be viewed in themselves, but as symbolic markers for the perspectival idea. Points on a plane are not expressions of quiddity but subservient signifiers of uniform space and time used to emphasise the illusion of solidity and homogeneity, and to deemphasise both the role consciousness has in creating and perceiving experience and the self has in forming space and time. We are, in effect, tricked into thinking we are viewing an accurate representation of reality, whereas we are actually viewing a highly abstract matrix of interlocking symbols .... This isn’t to say that artistic truth cannot be expressed in perspectival images (or that perspective is literally invented), any more than that truth cannot be expressed in abstract language. Rather, perspective is not an accurate representation but a realistic form of interpretation, and the cultural drive to worship this form, which began in the 1500s, ends up suffocating ‘unrealistic’ natural qualities and alternative, personal, expressions of that which is represented; not just individually, but collectively.

Here, Allen effectively outlines for us the reasons that, in his opinion, the "'objective' perspective" represents a further departure from the virtues of the panjectivity as the original aesthetic principle of humanity's artistic output, and which Allen identifies in his "Peanut History of Art," for which he provides examples throughout from the artistic record. However, Allen also records the social impact of these artistic techniques with an analysis that, in my opinion, would find favor with Walter Benjamin:

[T]he [R]enaissance also saw the erosion of the artisan and the craftsman. The idea of the ‘professional artist’ was foreign to human experience [in the Classical Era and the European Middle Ages] .... [but, since the Renaissance,] the taste of the middle and upper classes ... privileged form over function. The professional and possessing classes had, as they still have, a distaste for function—for material reality—built in from birth. They don’t, on the whole, do anything really useful, they don’t make or have to deal with real things, they don’t have to rely on real people for support or for the experience of their real senses for knowledge. They have a pre-programmed distrust of the future, which they view through the lens of financial security, and an inbuilt distaste for the imminence of matter and the transcendence of consciousness, all of which is reflected in their bizarre attitude towards art, which focuses almost exclusively on what the image is ‘about’, how it was made, who the artist is, what it reminds them of, how it makes them feel, where it is ‘situated’ (in history or philosophy) and of course, how much it is worth. To ask what the painting is actually of is taboo, a laughably naive question which has no place in serious art curation or criticism ..... The focus of the bourgeois critic on form, style and concept mirrors the drive of the bourgeois artist to speak through form, style and concept; because pre-formal sensory experience is distasteful to them both. {Moving into the 20th and 21st centuries,] he same is true of film (ooh, wonderful cinematography!) story (ooh, powerful language!) and each other (ooh, nice house!). The function, much less the reality, of art and life is simply off the menu for the formal classes .... The combined consequence of professionalism, romanticism and photography was, firstly, that artists began to once again consider their own subjective experience to be as important as the objective fact of what was happening, and secondly that the materials of art—the paint, the brush-strokes, the clay and whatnot—began to be seen as having as much communicative power as the image itself .... The result was impressionism, the beginning of modern art.

In sum, Allen identifies the aesthetics (and, whether implicitly or explicitly, the guiding ideologies) of what we'll call 'the upper-class tastemakers throughout centuries' as those privileging "form over function" resulting from "a distaste for function [as an expression material reality]," nurtured through what we might off-handedly call a well-off upbringing that has given them a "pre-programmed distrust of the future, which they view through the lens of financial security"—a lens, in my own interpretation, emerges from insecurity; i.e., 'I don't want suffer like I know the poor suffer'—and, altogether, an attitude toward art as a means not of transcendence but as escapism from the uncomfortable truths of the material conditions in which they live and from which these 'upper-class tastemakers' inevitably benefit due to their economic class.

More succinctly: the rich get richer, as we all know, but at the same time, our society's aesthetics (in the spheres of both the popular and the elite) cause the every individual in our society risks losing—if they have not already lost it—more and more of their human capacity to recognize artworks that represent what I have called "the experience of reality as a living creature alive of its own accord," and to enjoy the sense of personal transcendence that accompanies the appreciation of panjective art, to the point where the average art connoisseur can't identify panjectivity at all. As Allen turns his discussion to modern art, we see how the loss of our ability to recognize aesthetic panjectivity has produced not just common tendencies of modern art, but solidified "the art-world" as a credibility-granting institution.

When art turned again from considerations of objective reality to subjective impression[,] the focus of the critic, curator and artist turned to paint and canvas. This had the effect of changing taste from a matter of sensitivity to experience to a question of education. This in turn combined with the removal of art from life into the unplace of the gallery, and its concomitant commodification, to produce elite art; that which only the properly trained experts can really enjoy and commercial art; that which is valued for its authenticity and for its arbitrary price-tag, rather than for its quality. Another word for this elite, commercial art is pornography.

While I can't say that I share the same moral judgment against pornography that one may detect from Allien's quote, I see the relevance nonetheless: modern art tempts, but inevitably fails to satisfy, the human appreciation for what I will describe as 'the panjective experience of reality as a lived creature, alive of its own accord, that converts our external circumstances and internal lives into experiences from which we may derive either a sense of meaning to our lives, or otherwise, a sense of amusement at the circumstances of our external worlds, even as it employs both subjective and objective techniques in its composition, and therefore falls short of Allen's panjectivity. " As Allen further explains:

While art stills the mental-emotional self, revealing the ineffable ... porn moves; emotionally exciting the self, either negatively (fear, revulsion, disgust, etc.) or positively (arouses the appetites). The road towards pornographic art began as we have seen, long, long ago, at the dawn of ‘civilisation’, but as society has descended further and further into egoic unexperience [of reality expressing a life of its own], so art has become more and more pornographic until, in the last half-century or so, it has reached its logical end-point—hyperporn.

Allen covers this devolution into what he calls "hyperporn" in brief:

The first stage of artistic hyperporn was when the medium — of paint or clay or what have you—begin to form part of the artistic message. This process (combined with a new non-standard feeling for the quality of life) initially permitted the exquisite panjectivism of artists such as Turner, Monet and Van Gogh—the great impressionists (and post impressionists)—but soon developed into the degraded modernism of Picasso, Braque and Moore, in which art started to become its own subject, and then into abstract expressionism, in which the object became irrelevant. By the time we reach artists like Mondrian, Johns and Pollock (an employee of the CIA incidentally) experience had nothing whatsoever to do with art.

Accordingly, in Allen's view:

We have now reached ... the end of art[:] postmodernism. Now everything is irrelevant to art, which enables anything, anywhere to be presented and commodified as art. High and low culture collapse into a hyper superficial, self-referential market place which runs on pure whim — albeit professionally accredited whim. The gallery owner or wealthy collector decides that something is art, and, on this elite decision alone, it becomes valuable .... Hyperpornographic bullshit cannot gain access to the modern canon unless it meets one or more of these five postmodern.

Of Allen's criteria for a postmodern work of art, I find a particular resonance with his third criterion:

Irrelevance, intimately connected with extreme formality is the necessity of all modern art to have no meaningful bearing whatsoever to what is actually happening in the world .... Any art that is non-ironic, that takes responsibility for itself, that is in any way relevant to what is happening in the world, that seeks to still the emotions rather than excite them, that is genuinely exuberant or genuinely harmonious, that has an actual useful function in the world (such as decoration, illustration and so on) or which is technically superb is BANNED. It cannot function in the market.

So, if you're an artist and you made it this far (and you haven't yet realized how Steemit and other developments will help you create panjective art that may beneficially shift the guiding ideologies of our increasingly planetary society), then I suspect you might find yourself a little discouraged, taking Allen's analysis of modern art at face-value. That said, I believe you can use some of his other comments on "Artistic Lies" and "Artistic Truths" to help point your creativity in the right direction:

Artistic Lies[:] The disembodied nature of modern and post-modern art also explains why it all looks more or less the same, wherever it comes from and whoever produces it .... The fact that libraries are filling up with books on the ‘the philosophy of art’ is evidence that art itself is no longer fulfilling its pre-rational function. The experience of the seeing eye has given way to the ideas of the staring mind. We are not invited to resonate to the primal reality of the inspired image or form, but to think about an idea, and an extremely banal one at that .... This is why language is so important to post-modern artists, for what they create is not to be looked at, but to be thought about, discussed and traded by the critics, curators, journalists, dealers and academics who comprise the actual art world. It is they—businessmen and professionals—through their market-activities, who add the value that amounts to modern art, just as it is businessmen and professionals who add the value that amounts to modern farming, manufacture, care-work and so on, and they do this through the production of verbiage .... In fact, with experience now irrelevant, with everything (or everything that gets a price tag) now considered, potentially, as art and with even the object itself being secondary, you have ask why bother having the object at all? Postmodern art would serve its limited purpose just as well by being a descriptive placard.

For those of you who might feel comfortable enough simply knowing what to avoid, the above should serve as enough to get you started with creating more panjective art, and thereby subvert from below the ruling ideologies of both the art-world and (in so far as you may represent the aesthetics guiding those ideologies) of society at large.

That said, however, Allen also offers a description of what constitutes a panjective work of art depicting an artistic truth.

Artistic truth, as we have seen, is neither objective nor subjective; it is panjective. It manifests as the objective-subjective self—and, therefore, depends on objective technique and tradition and on subjective preference and style—but is paradoxically irreducible to either. We therefore find that artistic truth, or artistic standards, can appear anywhere within the entire self-spectrum; from the formal realism of Michelangelo, or Robert Crumb, or the transcendent craft of William Morris and Eric Gill, through the impressionistic genius of Hokusai, early Picasso and Egon Shiele to the formal abstraction of Insular art or Mark Rothko. We also find that artistic truth cannot appear at the extremities of the self-spectrum. The artistic standards bounded by the absolute objectivity of photography or digital virtual reality at one end and the absolute subjectivity of postmodernism and pornography on the other, in ruling out panjective paradox, are inherently hostile to artistic truth. And, finally, we find that when artistic truth does appear it nearly always conflicts with fashion—the artistic mob-rule of time, space, groupthink and groupfeel .... [A great artist] has overcome the pseudo reality of his self, which means he can see the miracle of sensory experience that lies beyond his mind and emotions, and he has mastered the tool of his self, which means he can do justice to the transcendent reality which presents itself to him, squirming in ecstasy.

So, hopefully that conclusion gives my artist-comrades some guidance and encouragement for creating works of art that may help to change the guiding ideologies of societies. Of course, I can't ever end a post without feeling as if I have failed to cover my subject in the detail in deserves. Still, I feel I'm spiraling at some pace toward a theory of aesthetic' effect upon ideology, which I will continue to investigate, though perhaps more sporadically.

Nonetheless, I wanted to leave you all with another example of how a work of art has provided me with an "experience of reality as a living creature alive of its accord," and so (spoiler warning) I will provide you with the final page of Roberto Bolaño's The Savage Detectives:

(Source) I don't mind telling you that, after I closed the book, I saw stars that crossed the limits of my optical vision: a phenomenon I just can't stop myself from invenvestigating further, so certainly look forward to the sporadic updates on this subject that I mentioned above. After all, Bolaño's "The Romantic Dogs" served as the subject for my post delaying this one, so I imagine there's a method to my madness that hasn't yet fully revealed itself. But until it does, take care!

Best (as always),

Holy smokes! I have to give this a more serious look when I'm more awake... that's quite the read! leaving this tab open for a morning of panjectivity... peace, b