"The main fuel to accelerate world progress is our reserve of knowledge, and the brake is our lack of imagination."

Julian Simon, The State of Humanity (1995)

The first oil crisis in 1973 gave powerful wings to the idea around the unsustainability of growth and the need to impose limits. A little earlier, in the late 1960s, Paul Elrich, a dark entomologist at Stanford University, wrote The Population Bomb, a warning book on how the rising population would condemn the human race to the inevitable famine of the 1980s. The proposal was to simply to put limits on growth. It was not a new idea. In the eighteenth century, the English clergyman Thomas Malthus warned about the risks of famine that faced humanity if it continued to grow. A vision of the economy as a zero-sum game also present in Marxism and which, mutatus mutandi, have reached our days in the modern forms of the Club of Rome or the seemingly novel theses of analysts such as Naomi Klein.

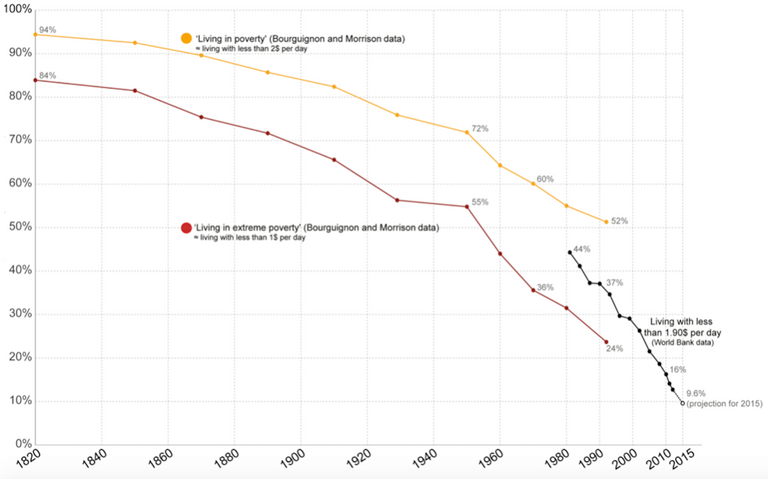

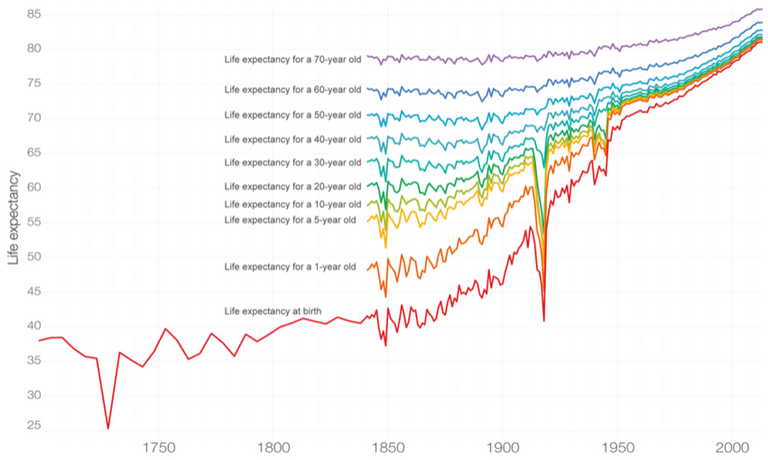

When Malthus wrote his thesis in 1779 the world population did not reach 1 billion, poverty was the natural condition of practically all, literacy was reserved for a strict minority, life expectancy barely reached 35 years, with infant mortality very high, and such conditions that even the King of France had to do his needs in the corners of the corridors of Versailles. Today, the world population exceeds 7,000 million souls and, as Johan Norberg reminds us in his book Progress, we all live better than ever. Poverty has been reduced as never before in the history of humanity, we have achieved that extreme poverty (living with less than $ 1 a day) affects only 10% of the world population, illiteracy, including countries in development, it only affects 16% of the world's population and the set of improvements in food, health and hygiene have allowed to increase life expectancy up to 72 years, among other notable improvements.

Population living in extreme poverty

Norberg's book includes high doses of 'history' and also of 'theory', following the dichotomy of the Viennese economist Ludwig von Mises. Theory that offers us a synthetic view of the main metrics that help to evaluate the progress of humanity in these last 200 years, basically since Europe launches its Industrial Revolution, and some brushstrokes, even if only superficially, on why pass. Why we improve.

Norberg summarizes the progress of humanity in terms of food, sanitation (access to running water), life expectancy, violence, environment, literacy, freedom and equality. Many of these tendencies feed off each other: better nutrition, the result of technological and scientific advances, has a positive impact on a longer life expectancy and a lower negative impact on the environment. All the above, affects, in the end, a greater accumulation of capital, both physical and human (think of education), which in turn is positively related to the reduction of violence or to enlighten more free and fair societies. In each of these chapters, the Swedish author interspersed elements linked to historical evolution, and an explanation of why this evolution occurs.

Life expectancy in England and Walles

Through the pages and relying on empirical data and case studies (on the important recent developments in India, China and many parts of Africa), Norberg discovers to the reader the concepts behind all these advances (the rights of property, the rule of law, institutional solidity or freedom of enterprise are just some of the great guiding ideas behind the great achievement of progress by humanity). A conquest, in addition, relatively recent. Norberg shows us how neo-Malthusian discourse systematically underestimates the incentives and creative, inventive capacity to solve the problems of humanity. Our imagination is infinite. Ronald Reagan is perhaps the one who put it more clearly when he said: "There are no limits to growth because man's capacity for invention is infinite." Reagan endorsed the thesis of Julian Simon, who cited in the frontispiece of this article, explained in The Ultimate Resource, a book in the same intellectual tradition as Norberg's.

One of the great virtues of the book is its synthesis and brevity. The author relies on many of the great economists and thinkers of the moment. In addition to the aforementioned Simon, on the improvements in issues of food and poverty, Norberg cites the classic works of Robert Fogel or Angus Deaton, the latter Nobel economics, Steven Pinker on issues of violence, or Bill Easterly, among many others, when he speaks of evolution in life expectancy. Many of the graphics and data have been worked by Max Roser, leader of the Our World In Data project (ourworldindata.org), a must-have website to quickly and graphically become aware of how the world has improved in the last two centuries.