In his last podcast, JimFear138 sat down with Rawle Nyanzi to discuss the concept of genres in a freewheeling discussion that spanned, among other things, My Hero Academia, the blurry line between science fiction and fantasy, and, at the 40:15 mark, Japanese light novels.

Rawle didn't have a high opinion of most light novels. I share the same sentiment. Yet light novels are the modern-day inheritors of the pulp tradition.

Within literati circles, it's fashionable to deride classic pulp fiction from the early 20th century as cheap, lurid and ultimately disposable fiction. Social Justice Warriors further insist that such stories are racist, sexist and all kinds of -ist and -phobic. Yet this seems to be a Western phenomenon: in Japan, light novels proudly continue the tradition of cheap, exciting entertainment, and far from being derided, are an integral and celebrated cornerstone of Japanese culture.

Light novels are short, inexpensive books on fast release schedules. Running to about 50,000 characters, they are small and lightweight, able to be carried about and read anywhere. This mirrors the pulp practice of publishing compact, fast-paced stories on equally compressed schedules. Well-loved in Japan and around the world, many LNs have been translated and exported across the world. But how do modern LNs compare to the pulps?

Consider the following:

The Adventurers Guild—created to support those courageous questing souls—was first formed, so it was said, by a handful of people who met one another in a bar. Unlike other workers’ associations, the Adventurers Guild was less a labor union than an employment agency. In the ongoing war between the monsters and “those who have language,” adventurers were like mercenaries. No one would tolerate the existence of armed toughs if they were not managed carefully.

Priestess stopped in her tracks as the vast branch office that stood directly inside the town gates took her breath away. When she entered the lobby, she was taken aback to find it bustling with adventurers, even though it was still morning.

These buildings boasted large inns and taverns—usually together—as well as a business office, all in one. Really, this kind of clamor was the natural result of providing these three services in one place.

For every ordinary human in plate armor, there was an elven mage with staff and mantle. Here there was a bearded, ax-wielding dwarf; there, one of the little meadow-dwelling folk known as rheas. Priestess wound her way through the crowd, past males and females of every race and age imaginable carrying every possible type of weapon, toward Guild Girl. The line snaked on and on, full of people who had come to take on or lodge a quest or to file a report.

This is from the first chapter Goblin Slayer, a famous dark fantasy series about the eponymous adventurer obsessed with conducting goblin genocide. The text is compact and easy to read, but it is all tell and no show. Phrases like 'took her breath away' and 'taken aback' lack power, because the sparse descriptions lack emotive power. The sentence 'No one would tolerate the existence of armed toughs if they were not managed carefully' feels aimed at the reader instead of being an organic component of the story.

This excerpt is simply a straightforward report of sights and peoples and business functions, revealing nothing substantial about Priestess, the people around her, the town or the rest of the setting.

Now consider this:

Torches flared murkily on the revels in the Maul, where the thieves of the east held carnival by night. In the Maul they could carouse and roar as they liked, for honest people shunned the quarters, and watchmen, well paid with stained coins, did not interfere with their sport. Along the crooked, unpaved streets with their heaps of refuse and sloppy puddles, drunken roisterers staggered, roaring. Steel glinted in the shadows where wolf preyed on wolf, and from the darkness rose the shrill laughter of women, and the sounds of scufflings and strugglings. Torchlight licked luridly from broken windows and wide-thrown doors, and out of those doors, stale smells of wine and rank sweaty bodies, clamor of drinking-jacks and fists hammered on rough tables, snatches of obscene songs, rushed like a blow in the face.

In one of these dens merriment thundered to the low smoke-stained roof, where rascals gathered in every stage of rags and tatters— furtive cut-purses, leering kidnappers, quick-fingered thieves, swaggering bravoes with their wenches, strident-voiced women clad in tawdry finery. Native rogues were the dominant element—dark-skinned, dark-eyed Zamorians, with daggers at their girdles and guile in their hearts. But there were wolves of half a dozen outland nations there as well. There was a giant Hyperborean renegade, taciturn, dangerous, with a broadsword strapped to his great gaunt frame—for men wore steel openly in the Maul. There was a Shemitish counterfeiter, with his hook nose and curled blue-black beard. There was a bold-eyed Brythunian wench, sitting on the knee of a tawny-haired Gunderman—a wandering mercenary soldier, a deserter from some defeated army. And the fat gross rogue whose bawdy jests were causing all the shouts of mirth was a professional kidnapper come up from distant Koth to teach woman-stealing to Zamorians who were born with more knowledge of the art than he could ever attain.

This man halted in his description of an intended victim's charms, and thrust his muzzle into a huge tankard of frothing ale. Then blowing the foam from his fat lips, he said, 'By Bel, god of all thieves, I'll show them how to steal wenches: I'll have her over the Zamorian border before dawn, and there'll be a caravan waiting to receive her. Three hundred pieces of silver, a count of Ophir promised me for a sleek young Brythunian of the better class. It took me weeks, wandering among the border cities as a beggar, to find one I knew would suit. And is she a pretty baggage!'

He blew a slobbery kiss in the air.

'I know lords in Shem who would trade the secret of the Elephant Tower for her,' he said, returning to his ale.

This is the opening of Robert E Howard's The Tower of the Elephant. The first three paragraphs paint a vivid picture of the Maul, presenting a visage of danger and lawlessness, violence and merriment; showcasing the many races of the world; and depicting an age of bloodshed and strife. The excerpt ends with a reference of the titular Tower of the Elephant, signalling to the reader that the story is about to begin.

Notice the similarities and differences between both scenes. In both excerpts, the action takes place in a meeting-place where adventurers can find work and sustenance. But where the prose of Goblin Slayer is bland and emaciated, The Tower of the Elephant spends some extra words to set the stage, making the scene come to life and setting the tavern in the context of the city, the world and the age. In the second excerpt, you can immediately grasp the violence and the danger seething under the surface, sense an age of blooded swords and broken shields, and wondrous treasures waiting out of sight. In the first excerpt, all you see is are words and the framework of a place.

No discussion of Japanese entertainment can overlook the isekai genre. Parallel world adventures, especially litRPG isekai adventures, have been a mainstay of Japanese fiction for close to a decade, chasing the success of Sword Art Online. Today, isekai stories featuring a weak and indecisive high schooler flung into a strange sword are so common that non-isekai fantasy fiction are a minority in modern light novels and manga.

But isekai fiction descends from the pulps too.

Isekai stories kick off with the moment the protagonist is transported to another world. The following excerpt is from Grimgar of Fantasy and Ash, a dark fantasy series praised for its alleged 'realism'.

He opened his eyes, feeling like he’d heard someone’s voice.

It was dark. Nighttime, maybe? But not pitch black. There were lights. Fire. Above him. Some kind of lighting. Candles, it looked like. Small ones affixed to the wall. Not just one, but many, spaced evenly, continuing as far as he could see.

Where was this place?

It was kind of hard to breathe.

When he tried touching the wall, it was hard and rocky. This was no wall. It was just bare rock. Little wonder his back was sore after lying against it. His butt hurt, too.

Maybe he was in a cave... A cave? Why would he be in a cave...?

Those candles were pretty high up. He might be able to reach one if he stood; that was how high they were. Moreover, they didn’t even give off enough light for him to see his hands and feet.

But he sensed the presence of others nearby. When he listened closely, there was a faint noise that sounded like breathing.

Humans? What if they weren’t? He might be in trouble. But they sounded human, somehow.

“Is anyone there?” he asked hesitantly.

“Uh, yeah,” a man’s voice shot back.

“I’m here...” came another response, likely that of a woman.

Another man’s voice gave a short, “Yeah.”

“I figured as much,” another person added.

“How many of us are there?”

“Should we count?”

“And... where are we, anyway?”

“Dunno...”

“What? Doesn’t anyone know where we are?”

“What’s going on?”

“What is this?”

Seriously. What the hell was this? What was he doing in a place like this? And why? How long had he been here?

This scene is weak. The descriptions are dull, the dialogue limp, the prose awkward. The main character comes off as dull and low-energy. He's just lying there, occasionally probing the area around him and listening to people, taking his own sweet time to realize something's wrong.

Further, the lines(it's barely even dialogue) from the people around him convey no information to the reader whatsoever. The main character doesn't interact with them, they reveal no useful information around the world, and their words lack energy and snap.

There is no build-up to the final line. There's no moment of revelation when he realizes something's wrong, no clues that something is out of place. This makes his emotional reaction feel cheap and forced. The register, too, feels juvenile and immature, and not in a good way; instead of conveying the energy and non-wisdom of youth, it merely emphasizes the main character's lifelessness. 'Realistic' this may be, but it sure isn't exciting.

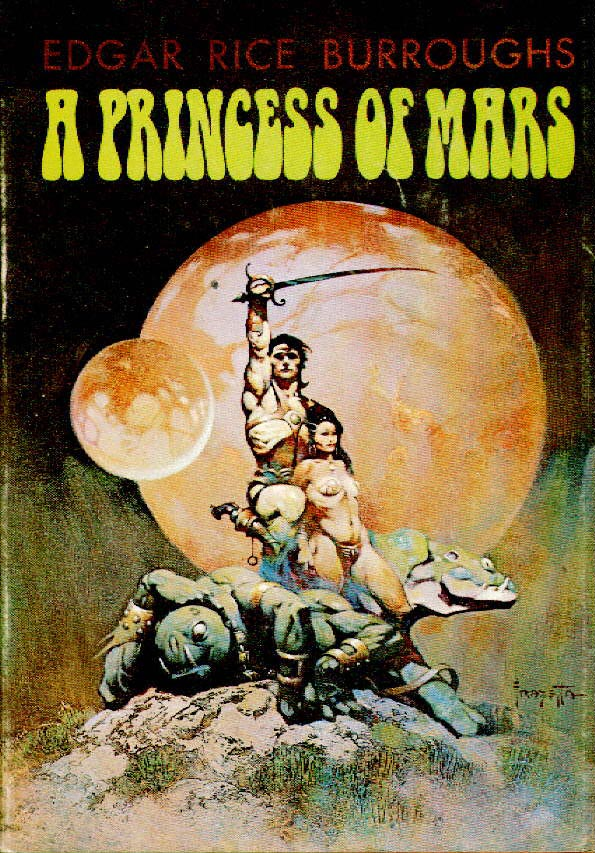

Now consider the following from the great grand-daddy of isekai fiction: A Princess of Mars.

Few western wonders are more inspiring than the beauties of an Arizona moonlit landscape; the silvered mountains in the distance, the strange lights and shadows upon hog back and arroyo, and the grotesque details of the stiff, yet beautiful cacti form a picture at once enchanting and inspiring; as though one were catching for the first time a glimpse of some dead and forgotten world, so different is it from the aspect of any other spot upon our earth.

As I stood thus meditating, I turned my gaze from the landscape to the heavens where the myriad stars formed a gorgeous and fitting canopy for the wonders of the earthly scene. My attention was quickly riveted by a large red star close to the distant horizon. As I gazed upon it I felt a spell of overpowering fascination—it was Mars, the god of war, and for me, the fighting man, it had always held the power of irresistible enchantment. As I gazed at it on that far-gone night it seemed to call across the unthinkable void, to lure me to it, to draw me as the lodestone attracts a particle of iron.

My longing was beyond the power of opposition; I closed my eyes, stretched out my arms toward the god of my vocation and felt myself drawn with the suddenness of thought through the trackless immensity of space. There was an instant of extreme cold and utter darkness.

...

I OPENED my eyes upon a strange and weird landscape. I knew that I was on Mars; not once did I question either my sanity or my wakefulness. I was not asleep, no need for pinching here; my inner consciousness told me as plainly that I was upon Mars as your conscious mind tells you that you are upon Earth. You do not question the fact; neither did I.I found myself lying prone upon a bed of yellowish, mosslike vegetation which stretched around me in all directions for interminable miles. I seemed to be lying in a deep, circular basin, along the outer verge of which I could distinguish the irregularities of low hills.

It was midday, the sun was shining full upon me and the heat of it was rather intense upon my naked body, yet no greater than would have been true under similar conditions on an Arizona desert. Here and there were slight outcroppings of quartz-bearing rock which glistened in the sunlight; and a little to my left, perhaps a hundred yards, appeared a low, walled enclosure about four feet in height. No water, and no other vegetation than the moss was in evidence, and as I was somewhat thirsty I determined to do a little exploring.

Springing to my feet I received my first Martian surprise, for the effort, which on Earth would have brought me standing upright, carried me into the Martian air to the height of about three yards. I alighted softly upon the ground, however, without appreciable shock or jar. Now commenced a series of evolutions which even then seemed ludicrous in the extreme. I found that I must learn to walk all over again, as the muscular exertion which carried me easily and safely upon Earth played strange antics with me upon Mars.

Instead of progressing in a sane and dignified manner, my attempts to walk resulted in a variety of hops which took me clear of the ground a couple of feet at each step and landed me sprawling upon my face or back at the end of each second or third hop. My muscles, perfectly attuned and accustomed to the force of gravity on Earth, played the mischief with me in attempting for the first time to cope with the lesser gravitation and lower air pressure on Mars.

The first three chapters of A Princess of Mars introduces the reader to the hero, John Carter, and details a mini-adventure that has him fighting for his life against a band of Native Americans. The first three paragraphs of this excerpt describe the moment of transmigration, while the remainder covers his immediate actions on arrival.

We can see here that John Carter is a dynamic, vigorous, inquisitive adventurer, a fighting-man who values beauty and battle in equal measure. The second after his arrival on Mars, he gets up and begins exploring his environs, and quickly encounters his first challenge: coping with Mars' lighter gravity.

The set-up in Princess of Mars is critical to the story's success. The three chapters prior to Carter's transportation establishes his character and describes the world he came from, creating a reference point for the readers to prepare them for the moment of transition when Carter goes from a familiar landscape to a strange world.

In Grimgar, the story opens with the main character awakening in darkness. Without lead-up, there is no reason to care about him and his past. While such a set-up can work, the main character must establish a unique personality right off the bat to hook the reader. Here, all I see is a passive dullard with unnatural pseudo-feelings. There is no reason for me to care about the MC.

Japanese light novels may mimic the format and publishing schedules of the pulps, but they do not necessarily live up to the standards established by the pulps. While some concepts and nuance may be lost in translation, if the base material is little more than dross, a translation won't produce diamonds.

To be clear, there are light novels worthy of your time and money. JimFear138 recommended Vampire Hunter D. But by and large, even the most popular LNs today tend to have subpar writing, so much so that by Western standards they would be considered amateurish or even unpublishable.

Why, then, are they so well-loved?

Rawle suggests that LNs offer escapism in a high-pressure grade-driven society. After all, it's better to have poor fiction than no fiction at all. When you're in the middle of a desert, you can't afford to be picky.

In addition, it's easy to look on the past with rose-tinted glasses. For every pulp grandmaster we can name, there must be tens, hundreds, even thousands of writers whose names and stories have been lost to history. Yet we only remember the former, because their works carry a universal appeal that endures across the ages. It may not be completely fair to compare modern light novels to pulp masterpieces.

The best I can say about trash light novels is that they are adequate. Like the pulps of days gone past, they are cheap, widely available, published quickly, cheerfully ignore genre conventions, and are written at an acceptable standard for their target market.

In this is a lesson for PulpRev: you don't need to produce perfect stories from the get-go; you just need to write stories that will interest your audience. And do so quickly.

With that said, PulpRev cannot settle for mere mediocrity. Churning out garbage is all part of the learning process, but if we keep improving our standards we're bound to git gud. However, if we just rest on our laurels and content ourselves with churning out low-quality trash forever, we're not doing ourselves any favours.

Within PulpRev circles it may be fashionable to dismiss Pink Slime and trash LNs for poor quality writing, but such stories make millions or billions annually, while we are still little more than a hashtag. Ask a reader on the street about grimdark or thrillers or light novels and he'll tell you the big names in their field; ask him about PulpRev and if he doesn't frequent our corner of the Internet he'll just look at you funny.

Our time will come soon. Audiences are beginning to rebel against the degeneracy in popular culture. They are sick and tired of creators telling fans that straight white males are all racists and sexists, of Social Justice Warriors trying to cram ideas down their throats, and screeching harpies trying to control what creators can create. As seen in the dismal performance of the latest Star Wars movies and in the shrinking Western comic markets, fans are abandoning the converged companies in droves. Soon the market will clamor for the fiction we specialise in--but we must become worthy of our audience and live up to the standards of the golden age of pulp.

We are the inheritors of Robert E Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Clark Ashton Smith, C L Moore and so many more. Japanese LNs may have adopted the publishing methods of the pulps, but most of them lack the literary genius that defines the pulp age. While we can study the marketing strategies, concepts, tropes and settings employed by modern stories, never forget that by and large LNs have not inherited the grandeur of the greatest pulps.

The pulps defined an era, and their legacy resonates even today; most light novels have merely copied everything from the pulps except what made them great. If we must choose between pulp wonders and light novel trash, always pick the former.

--

If you want pulp-style escapist fiction with action and humor in equal measure, check out my latest novel HAMMER OF THE WITCHES.

Thanks for the shoutout! I couldn't agree more, but I think you've touched off a spark in my own mind, and I think I have a post to build on this somewhat.

In any event, you're right. What made the pulps great was the writing, not the marketing. We can ape the marketing all we like, but if we don't bring that grandeur, that action, that good writing, that wonder, then we're not worth much more than the latest translated isekai light novel.

And I know we're worth more than that.

I've seen too much good material from the PulpRev to believe otherwise.

You're welcome.

PulpRev is capable of taking the world by storm. We have that potential. We just need to realise it, and adopt appropriate marketing strategies. Once we have both quality and marketing, the world is our oyster.

Great post. I've been hearing more and more about this Light Novel phenomenon and have mixed feelings...

Thanks. I honestly can't see the appeal of LNs myself, with some rare exceptions.