Critical Mess Theory: What Is It and How Can We Use It?

Michael Zinman. Think a little bit of this:

Hello, Steemians! As you may well know, the graduate students of #explore1918 are close to deciding on a Philadelphia public history project to fund, but we still need to determine what criteria we want our eventual recipients to meet. This week, we read two profiles of eccentric bibliophile and avid collector

And even more of this:

Today, I want to discuss Zinman’s collecting style, critical mess theory, and whether we should use it as a marker for who and what to fund. Let me explain:

The critical mess theory is a concept developed by Zinman to half-jokingly describe his collecting habits. In his view, collecting should be unencumbered by taste or convention. The only way to become a “connoisseur is to work in the entire spectrum of what’s available—from utter crap to fabulous stuff.” (Singer, 66) The public history field would benefit enormously by adopting the founding ideals of the critical mess theory. This theory supports a more emotional and inclusive field of history, and full disclosure, I’m a little in love with it.

For the Love of Stuff

In traditional history academia and even public history scholarship, we’re directed to start with historiography and eventually move to the “stuff,” meaning that we should gain a full understanding of what has been written about our topic before embarking on our own journey into the archives. For the past 8 years, I have not questioned this method—though I have often hated it. If we as public historians start by exploring sources and becoming informed experts beyond secondary materials, then our interpretation and visitor mediation begins with a decidedly less stodgy tone. We’re starting the project with emotional appeals and passion for history, rather than “trying to prove x,” as Zinman’s colleague states.

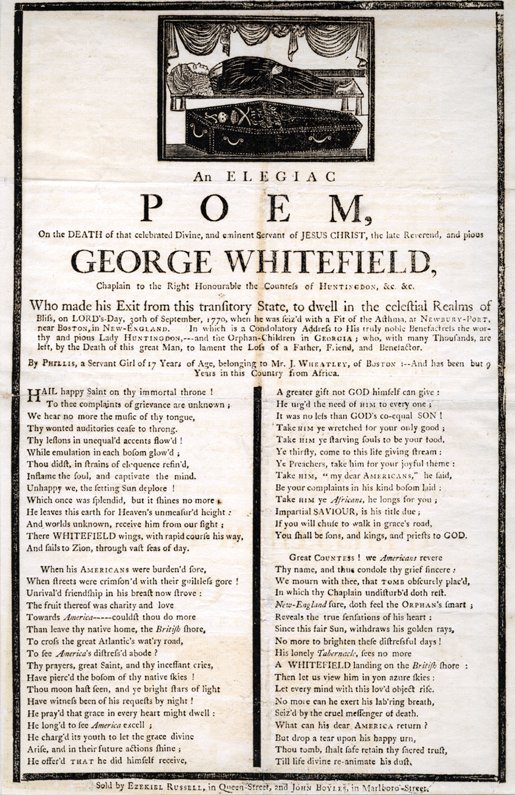

Outside of interpretation and public programming, the critical mess theory lends itself to over collecting without a connection to historical theme or the abilities of your given archives. James Green struggled to describe Zinman’s sale of 11,500 Early American prints to the Library Company of Philadelphia because there were too many different directions (historical time periods, themes, materials, etc.) to keep straight. A critical mess is hard to interpret for the public and thus usually overwhelming and inaccessible. For example, how do you plan the interpretation of a collection that contains a Phillis Wheatley original and America's first Sex Manual?

Head here for the Wheatley broadside in the Library Company's digital archive.

However, I still want to fund a project that's not afraid to get messy.

The critical mess theory has the potential, if modified, to energize public history institutions, and I think the personal story of Zinman’s collecting offers a potential scholarship criteria for us to explore. Would our chosen recipient, like Zinman, draw connections between high art, rare historical artifacts, and the hot mess of everyday life? Alternatively, would our chosen recipient, like the Library Company of Philadelphia, collaborate with and center the voices of community historians and collectors? Michael Zinman is not a published book historian; he is a man with a deep knowledge of and passion for printed material. I want to fund a project based in an unbridled passion for history: one that opens its doors and resources to community experts and is probably going to get pretty messy.

Sources:

James Green, The Zinman Collection and the Library Company. (Philadelphia: The Library Company, 2001), pp. 27-45.

Mark Singer, “The Book Eater: Michael Zinman, obsessive bibliophile, and the critical mess theory of collecting.” The New Yorker, February 5, 2001, pp. 62-71.

Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's

Zinman may have accomplished, in small form (miniature is too diminutive a word) what the Library Company did over the centuries. That might be why his collection was such a good fit for theirs. Yet, many institutions strenuously avoid the "critical mess" approach. It would be interesting to look at the value, or potential, of this theory across the institutional ecosystem.

I think thats awesome @chelseareed

Thanks, @artemis94!