I have recently become fascinated by China. Specifically, with China's attitude toward women. And to share my findings, I'd like to begin with a look at a few characters of the Chinese language and after that, I'll examine the portrayal of women in Chinese literature, both ancient and modern.

女: Pinyin, "Nǚ (the vowel sound in this does not directly correspond to anything in English but it's almost identical to the 'ö' in Swedish)": Chinese character meaning "female"

又: Pinyin, "Yòu (pronounced 'yo'): Chinese character meaning "also"

奴: Pinyin, "Nú (pronounced 'new'): Chinese character meaning "slave"

驽: Pinyin, "Nú (pronounced 'new', exactly as above): Chinese character meaning "inferior"

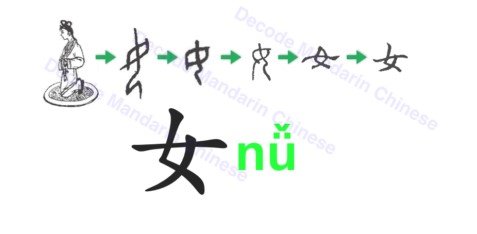

I would like to begin with the symbol that exists in all of these Chinese characters: "女," meaning "female." Perhaps the clearest sign of how the Chinese view women is to look at the origin of this character. Simply put, the character is an abstract drawing of a woman. Specifically, according to decodemandarinchinese.com, of a woman on her knees.

Well now, that's a rather simple place to start, isn't it? The Chinese symbol that means "female" is formed with the central axiom that a woman's place is on her knees. Of course, this is not simply a one-off, cherry-picked example either.

Notice, the character 奴, meaning "slave," is created by the character for "female" and the character for "also" being pressed together. This leads to the impression that the Chinese definition of a slave is "one who is also a female," or "one who has been made female." In essence, the Chinese concept of slavery is thus defined as "being like a woman."

Of course, the habit of shoving another, simpler character into a more complex one does not always serve as an explanation of meaning, but is sometimes a pronunciation hint. In modern China's quest to save face in front of the West by denying that they are an inherently Patriarchal society (like that's a bad thing??) they often try to say that this presence of the radical "女" in "奴" is an example of this phonographic, rather than semantic component.

However, this doesn't wash for two reasons. The first is that while it is true Mandarin itself didn't exist until 1920 (a little dynasty), Hanzi characters themselves are so old that many of them can be traced to cave-drawings (Han, pp. 15-21). These ideographs (and the implied meaning) have been part of hundreds of different dialects of the Chinese language family over thousands of years, and they have not always had such similar pronunciations. In other words, the pronunciation of these characters is new, the meaning has been around since before China was China. It is clear that putting the ideograph for "woman" into the ideograph for "slave" was designed to show meaning, rather than pronunciation. The presence of the radical for "woman" in the character "驽," meaning "inferior," is another sterling example.

The second reason to doubt the "oh, it's only there as a pronunciation hint" explanation is that there exists plenty of other evidence of this near-synonymity (if that isn't a word, it ought to be) between 女 and 奴 in Chinese thinking. In her novel The Good Earth, a novel by born-and-raised China expat Pearl S. Buck, nearly every character uses the words "girl" and "slave" interchangeably. An example is when O-Lan, who has jubilantly given birth to several sons, gives birth to a girl in Chapter 7 with no reaction other than "It is only a slave this time - not worth mentioning (p. 46)." Nor is it only O-Lan who does this. Wang Lung's(1) uncle also makes the same declaration.

The person in my house has told me, he said, of your interest in my worthless oldest slave creature [daughter]... She should be married. She is 15 now. (p. 51)

That's not just a Western perception either. The Chinese admit this in their own government-sanctioned textbooks.

In Chinese traditional culture, sky is higher than the ground, so is man above woman... A Chinese child will fall into this ethical custom before birth. Upon birth, the child will be treated differently by sex. For example, boy [sic] will have a family name and personal name and alias, while girl [sic] will will have only a family name, and upon marriage, she will follow her husband's family name... Therefore, women could hardly build a personality in such a dependent life. -Shi & Chen, p. 101

This too is quite plain. Not only are men described as being as far above woman as the sky is above the ground, but take note; women were not even given a name at birth (Lu, 166)! Names, after all, implied an identity, and there was no belief anywhere in China that a woman had such a thing. A woman was not entitled to possess wealth. A woman was part of the wealth a Man could possess.

The further one delves into China's literature, the clearer it becomes that a woman was an object and not a person. In fact, a woman was the kind of object a man could choose to keep in his tomb with him to use for his amusement on the journey to the next life. Qin Shihuang established this practice by ordering his entire harem to buried with him, alive, since decomposition might spoil their beauty and make them less valuable (Zhang, p. 18). The Ming Dynasty, which came much later, recognized the value of this practice in keeping widows from taking over the estates of their husbands/owners, and made it standard practice (Parkes).

This status of women as objects in Chinese traditional culture is put on vivid display in Luo Guanzhong's epic, Three Kingdoms (often mistranslated as "Romance of the Three Kingdoms").

[Don Zhuo] seized the women and other commodities that the people had with them and loaded everything onto his carts, tying to the sides severed heads - over one thousand... The heads were burned at the city gate; the women and the other goods were distributed among the army (p. 65)

"General, why not seek out the patriarch Qiao, procure his daughters with a thousand pieces of gold and dispatch someone to deliver them to Cao Cao? Once they belong to him he will be content and return to the capital." (p. 779)

Look at the phrasing: "women and other commodities; acquire the girls, for a purchase price. The recurring theme here is "men are people, women are possessions." Of course, one of the most undeniable examples is on p. 313 and 314 when Liu Bei (the hero of the epic) seeks refuge and food in a commoner's house and the commoner serves a peculiar tasting meat dish to him. When Liu Bei walks into the kitchen, he sees the severed arms and legs of the man's wife and realizes that he, owning no other livestock, slaughtered her to serve her as a meal for his guest. And Liu Bei, rather than being repulsed by this, is impressed. I remind you, Liu Bei is the book's hero, and hailed throughout the epic as a model of virtue.

Ergo, we're meant to see "oh, if someone cooks their wife to serve to you as a meal, you should be grateful that he thought enough of you to sacrifice his most valuable livestock." Or, at least, this is what the Chinese writer Luo Guanzhong wanted readers to think. And the fact that this has become one of the four epics upon which all of Chinese literature is built tells us that Chinese society does not find that notion too disagreeable.

...Now, I am an avowed anti-feminist. I think my articles on the virtue of male dominance and polygyny, together with my fondness for Master-and-slave-girl erotica (to say nothing of the fact that my lifestlye and living arrangements sound like they are lifted straight from one of these stories) makes that fairly obvious. Yet even as the anti-feminist I am, I think "darling, you're going to be delicious" is probably a step too far. I understand that as a woman, my place is in the kitchen, but I don't think that's quite what was meant, ha ha. Still the point is that this passage from Three Kingdoms demonstrates the ancient Chinese view of a woman. She wasn't so much a member of the household as she was simply part of a Man's wealth, to do with as He saw fit. She was His to be used, expended, and disposed of as he saw fit in pursuit of his goals.

You know, I don't find Chinese men even remotely attractive, but I'm starting to realize why I have always found a certain charm in the way they treat me. This idea of a man who takes it as axiomatic that my role is to simply accept, obey, and keep quiet, from a man who never questions his ability to enforce that, is an unquestionable turn-on. To the Chinese, a man is "He," and a woman is "it."

Frankly, the West (which is currently mired down in feminist nonsense) could learn a great deal from that simple concept.

(1) This spelling comes from before PinYin existed. In light of the fact that a character asks Wang Lung later whether his surname is the "dragon character (龙: Lóng)" or the "deaf character (聋: Lóng)," it's fairly safe to assume this would be "Wang Long" in modern Romanization.

Bibliography

A Little Dynasty Staff. "History of Mandarin Chinese." A Little Dynasty Chinese Language School. Web. 12 Feb, 2022. https://www.alittledynasty.com/history-of-mandarin-chinese.html#:~:text=When%20Mandarin%20was%20first%20officially,China%20are%20literate%20in%20Mandarin.

Buck, Pearl S. The Good Earth. New York, 2004. Washington Square Press.

ISBN 9780743272933

Han Jiantang. Trans. Wang Guozhen & Zhou Ling. Chinese Characters. Beijing, 2016. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-7-5085-3375-9

Luo Guanzhong. Trans. Moss Roberts. Three Kingdoms. Beijing, 2015. Foreign Languages Press.

ISBN 9787119005904

Lu Xun. The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China - The Complete Fiction of Lu Xun. London, 2009.

ISBN 9780140455489

Parkes, Veronica. "The Ming Dynasty Concubines: A Life of Abuse, Torture and Murder for Thousands of Women." Ancient Origins. 2 July, 2018. Web, 12 Feb, 2022.

https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-famous-people/ming-dynasty-concubines-life-abuse-torture-and-murder-thousands-women-007965

Shi Zhongwen & Chen Qiaosheng. Wang Guozheng. China's Culture. Beijing, 2011. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-7-5085-1298-3

Sima Qian. Trans. Wang Guozhen. Selections from "Records of the Historian". 2017, Beijing. China Intercontinental Press.

ISBN 978-7-5085-3050-5

Zhang Lin. Trans. He An. The Qin Dynasty Terra-Cotta Army of Dreams. 2005, Xi'an. Xi'an Press.

ISBN 978-7-80712-184-8

I see you made good use of my library, ha ha. It seems you've also adopted my habit of including a bibliography. Bit of an eccentric perspective though. ;-)