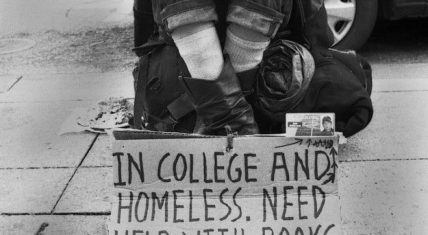

This document is an expose of the trials and tribulations that I have faced not only as a college student enduring homelessness—“economic and residential insecurity” is the personal term used here—but also as a disenfranchised first-generation black American looking to establish a new standard of existence for future generations. It was originally published in the Spring 2016 edition of Undergorund, Georgia State University's student-run literary journal.

My Experience and Its Context

Regularly finding comfortable places to sleep in Atlanta is hard to come by when you are dealing with “residential and financial instability,” my personal term to describe how one fluctuates between establishing his or herself in a safe environment called home and being left to make it on the streets. Nearly all of my days throughout the Summer 2015 semester, when I took Discrete Mathematics and Introduction to Sociology (eventually getting a Hardship Withdrawal via the Office of the Dean of Students), would end by me sleeping at the Library, on the MARTA buses and trains, some of the Atlanta Beltline stops, the benches near the Sam Nunn Federal Building, and the steps of the John C. Godbold Building (also known as the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals) in the Fairlie-Poplar District. On August 20, 2015, however, I wanted to minimize the time and distance I had to walk to get breakfast at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception and, eventually, to Library North for some studying. Entering Classroom South, which usually opened around 6 a.m. each morning, seemed like the most prudent and obvious thing to do because that is what I usually did if I wanted to get some extra hours of sleep. This day, however—Thursday, August 20—would wind up being a day that lived in infamy as I became the victim of and witness to a Pearl Harbor of bureaucracy, stand-offishness, disdain, and another preview into the pervasiveness of the Blue wall of silence.

Being the genius that I am, another homeless student and I overslept on those comfy couches on the fifth floor of Classroom South and Officer Perkins rode in one of those annoying Segways and asked for my student ID. Here is my recollection of how the confrontation went down at around 9:15 a.m. that morning:

[Perkins, on Segway]: Can I see your ID?

[Me]: (gives him PantherCard for check with Dispatcher)

[Perkins]: Are you a current student here?

[Perkins]: Do you have any business in this building?

[Me]: Well, I was just getting some rest in before I do some work.

[Perkins] (chuckling): And, um, what type of work do you have to do that is in this building?

[Me]: I was just planning on doing some work in the Library.

[Perkins]: And which buildings will your classes be in this coming semester?

[Me]: I don’t know, I forgot.

[Perkins] (chucking, annoyed and stern tone and countenance): I don’t think you understand—unless you have permission, you’re not supposed to be here. I don’t wanna see you in here again. [PantherCard check is completed, Perkins escorts me down to the first floor before I walk out.]

Similar treatment from a female Georgia State police officer towards Damian Whitaker, a close friend of mine and fellow homeless college student sleeping directly across from me, is what makes this entire episode more disheartening for me—and a larger indictment against the Georgia State Campus Police in general—because he is one of the most important people advising and inspiring me to push forward and permanently solve my issues. Law enforcement officials like Perkins and most of his other colleagues, however, behave in a manner that almost succeeds in being a roadblock to my development by using their authority as the foundation upon which they can build a mystique of “zero tolerance” and a “safe space” where the stereotypical college student can thrive. Being a non-traditional homeless college student, however, almost gives Perkins et. al. the green light to treat me like a white tee-wearing deviant hanging at the gas station. I was, once again, officially a second-, if not third-class citizen because my inability to achieve prior goals in the past empowered Perkins to treat me the way that he did in the present. I needed time to recover, reflect on what just happened to my friend and I, calm myself down before I did something I would later regret because I still had my to continue my bodyweight exercise routine that evening. I was going through the same nonsense that happened to me during the Summer 2005 semester here at Georgia State, my first bout of the homeless college student life where I would contemplate suicide as well as become an atheist. (My oldest nephew and one of my cousins in New York are the only two members of my Liberian-Grenadian family who know these two facts about me.) Eventually, I would speak to Fallon Proctor and Anitra Patrick, the Student Advocacy leaders at the Office of the Dean of Students, and partially alleviate the shock of the event at Classroom South by telling them what happened.

The conversation between Ms. Proctor, Ms. Patrick, and myself is changing the course of my life as you read this--and will eventually be the cornerstone of a revolution in how institutions treat transient and non-traditional students. Development of this essay is a culmination of the losses, anger, sadness, and regrets that have taken over my adult life like a salt being supersaturated in an aqueous solution. Suppressing this phenomena helps no one except those who have a vested interest in seeing poor and/or black American men in a permanently subservient state, and I am not about that life. The pieces to my puzzle of existence are being picked up and arranged by many hands, so perhaps this initial homelessness essay will serve as the moment where I actually put them together, conveying an image of the purpose that I established for myself. My purpose, whatever I consider it to be, actually fluctuates based on all of the knowledge and information I have received while this and many more tribulations, but originates from my challenging history as a first-generation American whose parents (let alone other family members and friends) deemed me their “prodigal son.” Acting on the behalf of other homeless, foster care, and otherwise non-traditional students requires me to give you a brief understanding of how I got to this point in the first place.

My father, from St. George, Grenada, met my mother, emigrating from Monrovia, Liberia, in a park in Brooklyn, New York in 1981. They would get married a mere three years later and give birth to me at the Kings County Hospital Center on November 15 of that year. It was obvious that I displayed an attachment towards sports and learning new things, especially considering that my parents are avid sports lovers and recorded many a game on VCR players. My development, combined with degradation of our neighborhood via the War on Drugs, influenced my parents to move to Clarkston, GA while one of my older brothers would enroll at Massanutten Military Academy in Virginia before going to Staten Island, NY and graduating from New Dorp High School in 1996. The time spent in Clarkston, and then Riverdale High School from 1998-2002, would be the first environments that truly set the table for who I am today--being a designated Scholar Athlete, four years of football and two years of track and field. Being a young man of direct Afro-Caribbean heritage is never easy because the aforementioned “prodigal son” reputation hoisted upon me exposed me to such pressure that I would wilt at the very thought of failing. Witnessing many unique family difficulties--specifically immigration issues, multiple financial hardships, and verbal and psychological abuse from my mother to my father--reinforced the desperation I felt to take my family out the hood. (Some family members and I came to Riverdale around the tail-end of that city’s “white flight” period in the late 90’s.) My inability to truly develop a form of resiliency, based on this extreme fear of failure negatively affecting my athletic and academic performance, resulted in my violating the Honor Code—cheating on a Calculus I exam—at Sewanee, the University of the South during the Fall 2002 semester.

The shame and embarrassment associated with being a “cheater” and a “flunk-out” was the first moment in my life where I not only doubted my family’s ability to groom me into a success, but also doubted my own capacity for overcoming adversity. Nothing seemed real any more: I couldn’t believe that my failure to properly prepare for the Calculus exam resulted in my expulsion from Sewanee, and I had no way of anticipating the vitriolic backlash that originated from many of the same family members and friends who claimed to love me with all of their hearts. Nothing seemed possible anymore: the fall from grace was swift, overwhelming, and I was erroneously used as an example of what will happen if one’s parents do not get the respect and admiration they claim they deserve.

The next 12 or so years have mostly been a long episode of unfulfilled potential associated with four separate bouts of homelessness, clinical depression, and Body Dysmorphic Disorder. I eventually enrolled at Georgia Perimeter College and transferred to Georgia State by the Fall 2004 semester. Continued emotional, psychological, and financial hardships resulted in the aforementioned Summer 2005 events, followed by a lengthy dead period of self-directed studying, traveling throughout the East Coast, gaining and losing friends, struggling to find suitable jobs, and realizing that I truly have the power to choose who enters and exits my life. 2014 was the year where some semblance of progress was coming into fruition when the Enrollment Services Center approved my Satisfactory Academic Progress appeal letter—which was completed in 2012, but I was too scared to turn it in—before the Summer 2014 semester. This occurred right on time because I was able to find a bed in the University Lofts with two roommates and permanently (I hoped, at least) rid myself of my mother and biological sister (who attempted to illegally kick me out of her Lawrenceville home). Despite my making the Dean’s List during both the Summer and Fall 2014 semesters and having a meal plan, many problems did not go away. I was still struggling to find work, still struggling with my college football and bodyweight workout routines, and missing out on scholarships and Federal Work Study. My “residential and financial instability” continued as I was forced to move to an off-campus house during the Fall 2014 semester and ultimately spent the Spring 2015 semester living with a friend and his family in Alpharetta.

Things started to look up for me as a friend of mine convinced me to move into a different off-campus location in the Lakewood Heights area of Atlanta right after my Spring semester Final Exams. By June, however, my situation took a turn for the worse once I found out that the residence was supposed to be vacant and I legally had no business being in that property. There was nothing I could do and quickly found a storage space and left by the first week of June. What occurred up until the second week of this past October was, for lack of better terms, a “remixed” version of my Summer 2005 melodrama: a smorgasbord of disrespect, misunderstanding, panhandling, arguments, lack of confidence, and exemplifying the same stereotypes and images about homeless people that I risked my life trying to avoid. My unwillingness to contemplate or plan a suicide attempt was the major, if not only, difference between 10 years ago and today because I was actually hired by Nick Vogt of the Georgia State Panthers Football program as a Student Assistant Equipment Manager amidst all of this turmoil and they accepted me from the first day I stepped in the facility. (Mr. Vogt fired me the Monday before the Georgia Southern game for making too many mistakes and allegedly mistreating a game-day volunteer after the Panthers’ 31-21 victory over the Troy Trojans.) My daily routine fluctuated much more often than I would have liked because, besides the fact that I was way too tired at times to do some things that I should have been doing, I was once again allowing other people and institutions dictate how I navigate through my environment. What follows now is a brief insight into how I negotiate these experiences in order to remain goal-oriented.

Conveyance of the Problem

Prejudices and interrogation techniques from the local police, not to mention the prejudices and biases from other people as they stare me down, are the most challenging ordeals that I faced every day that I was homeless (whether I was a college student or not). Security guards and law enforcement officials profile me up and down from the millisecond they see me; they have already made up in their minds that I “don’t belong” in the vicinity and do not give a flying mallard duck what I have been through before I entered their range of sight. Carrying anywhere from 30 to 70 pounds of my most important belongings makes me an outsider. There were multiple incidents where officers, predominately from the Georgia State Campus Police and City of Atlanta Police, would attempt to make me incriminate myself or “lead the witness” outside of the court system process; the most recent example of this was in early October, before moving into the University Lofts for a second time, when an officer approached me at Student Center West and blatantly asked “Don’t you have a CTW (Criminal Trespassing Warning) at Classroom South or somewhere on campus?”. And like many previous episodes over the years, about three or four fellow officers would enter the scene for the sake of “strength in numbers.” Many of these same cases are where the officers are quite familiar with me already but must proceed with their methods of checking my identification cards.

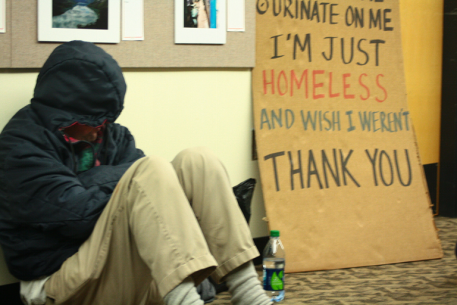

Maintaining some level of sanity and self-appreciation amidst the general stereotypes against homeless people is another significant barrier to my goals. Carrying four or five different bags everywhere I went did not help matters, but I dealt with it while still attempting to conduct myself with honor because none of these people contributed to my struggles. They need not burden themselves worrying about how I became homeless to begin with because I take full responsibility for my actions and decisions that put me in such a position. Nevertheless, this does not prevent many people from reporting to the police because they do not think I “belong.” This does not prevent people from assuming that I have given up on my life and, consequently, that I am not worthy of being in their presence or conversing with them. This does not prevent my fellow schoolmates and classmates from staring up and down at me like I could infect them with something via vector transmission. Homeless people throughout the metro Atlanta area are considered a nuisance rivaling that of a West Nile virus-infected mosquito and being a college student does nothing to deter this attitude. For some people, the phrase “homeless college student” is so oxymoronic that their vantage points and interpretations of my condition worsen as time progresses.

“Why don’t you stop begging for money and get a job?”

“Stop eating out of trash cans!!”

“How the fuck are you in college, but can’t find a place to sleep? That don’t make no goddamn sense.”

“If you’re really homeless, you should be thankful I’m giving you this sandwich to eat.”

“Take care of yourself. Jesus loves you and so do I.”

“My brother used to be homeless and now he’s doin’ somethin’ with his life. He got a car, job, house, everything. If he can do it, they why can’t you do it?”

Some embellishment or variation of the statements above have been preached towards me over the years whether I was homeless or not, but seem to be used in some perverse sort of motivation that doubles as condemnation for not keeping up with the Joneses. When one takes gender and racial expectations into account, he/she can predictably reach the conclusion that people look at me as a lost cause, a statistic, another black man who could not cut the mustard. I am pretty used to people looking right past me as if I am part of the background. I have adapted to people demanding that I take their plastic bag full of junk food—I am including peanut butter-and-jelly and bologna-and-cheese sandwiches—and bottled water because, as a homeless black man, I cannot afford to reject anything from anyone and my nutrition standards do not really matter. College football and sports science expert dreams be damned, many people do not consider me to be a “true” or “real” homeless person unless I have disheveled clothes and hair and promise to apply for 50 jobs in a week.

Logistics and upholding a workable schedule for information and services were also a struggle when I was persevering throughout homelessness. Since many organizations for particular goods and services are spread throughout the metro Atlanta area, making certain to go to certain places (assuming I have a MARTA Monthly Breeze card, of course, because I do not know how to drive) for specific services is paramount to my survival. Many places, particularly homeless shelters, have intake processes and assessments only for certain days and hours each week; missing these days may mean that it could take weeks, if not months, to get what I need. Food pantries, clothing closets, career development centers, and networking functions are also frequent but spread out and open during their own hours—so that subsequently means a potentially lengthy delay in accumulating resources to get ahead. Some services get cut short or are no longer provided because of employee deficits, waiting lists for clients, and public policy changes. These inopportune changes do not even account for how much stuff I must always carry with me when I am homeless. Going to some areas is very challenging because I have to take many breaks and always keep track of how much or little time I have to make it to my destination(s) each day.

The seriousness of all these problems are incrementally lessening, but still generally exist, by the day because of Georgia State’s Enrollment Services Center approving another Satisfactory Academic Progress appeal, which included a successful Hardship Withdrawal for the Summer 2015 semester after making a C in Introduction to Sociology (SOCI 1101) and making a D in Discrete Mathematics (MATH 2420, which I repeated and passed with a B this past Fall semester). Exposure to the police has dropped off exponentially since moving into the University Lofts. I am a regular at the Panther’s Pantry, located in the Parking Lot basement of the Urban Life Building. My sleeping and exercising habits still fluctuate because I am so busy, but the paranoia and mental preparation for physical altercations have certainly lessened. My haphazard memory retention and continued efforts towards landing employment and getting EBT and health insurance are the only major goals that I have yet to achieve. Each day that I stare at the downtown skyline through my Lofts window is an opportunity I take to intensify my focus on everything that is still possible and achievable for me. Dwelling on my failures and missed opportunities still occurs periodically, but I typically overcome that instinct by reminding myself that I still have the necessary faculties to create a redemption story for the ages.

Exploring Potential Solutions

The pursuit of redemption, for me, means realizing that I can use my talents and determination to positively influence many approaches towards societal problems that I witness or exemplify. Setting the example through my own conduct in the Georgia State community is the approach I should use to convince people that we can all improve each other’s existence. Conducting myself and treating others with respect, appreciation, courtesy, and a desire for long-lasting success will combine to be the foundation upon which my homelessness activism platform will be built. An ethical code based on critical thinking skills and the scientific method will engender the reputation I hope to put forth as a man of principle who will help other homeless and foster care students conquer their circumstances to change the world. No matter what, my pledge is to listen to people’s concerns, show compassion, provide my own perspectives, and follow through on whatever I say I do. This pledge can be summarized by the New Ten Commandments as posited by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in his classic work The God Delusion:

1.Do not do to others what you would not want them to do to you.

2.In all things, strive to cause no harm.

3.Treat your fellow human beings, your fellow living things, and the world in general with love, honesty, faithfulness and respect.

4.Do not overlook evil or shrink from administering justice, but always be ready to forgive wrongdoing freely admitted and honestly regretted.

5.Live life with a sense of joy and wonder.

6.Always seek to be learning something new.

7.Test all things; always check your ideas against the facts, and be ready to discard even a cherished belief if it does not conform to them.

8.Never seek to censor or cut yourself off from dissent; always respect the right of others to disagree with you.

9.Form independent opinions on the basis of your own reason and experience; do not allow yourself to be led blindly by others.

10.Question everything.

Students who are displaced can see me as a confidant who has their best interests at heart because I will do everything I can to live by the aforementioned ethical code. Applying this philosophical system to my life to enrich others’ lives must occur in the form of realistic solutions that get them off the streets and conveys the space they need to fulfill their own goals.

My proposal is a housing- and support system-oriented approach informing these people with both words and actions that they are as valuable to the Georgia State and city of Atlanta communities as any other student. Helping these students improve their financial standing so that permanent housing is affordable is the first step in embracing their presence among their Georgia State peers. Developing specialized scholarships and grants for students enduring displacement, via the Enrollment Services and Scholarship Resource Centers and the Georgia State Alumni Association, must be a top priority so that displaced students can increase their chances to pay for suitable housing and keep up with typical living expenses. Showing compassion to people in these dire circumstances with credible information and tangible resources will encourage these individuals to remain focused on their studies at Georgia State. Regardless of displaced students’ employment status, they must be connected to on- and off-campus career centers and networking organizations (e.g. Crossroads Career Services, Atlanta Workforce Development Agency, Atlanta Regional Commission) to put themselves in the best positions for professional development. Crowdfunding, microloans, and free (or reduced cost) bank and credit union accounts could also help displaced students tremendously by creating pathways to financial literacy, not to mention reducing the fear of missing another semester because of insufficient funds or funds being processed after deadlines.

Students enduring residential and economic instability definitely need to be shown that professors and counselors are sympathetic enough to point them in the right direction as well. The need for Georgia State professors, faculty, and staff to give proper references throughout students’ careers underscore the fact that it is people who do things for people. When anyone from the Georgia State community takes time out of his or her schedule to help a student endure financial and emotional hardships, it sends a message that we believe in, care for, and look after each other. Nothing can be taken for granted when it comes to navigating the college years, one of the most crucial parts of a person’s development because of the relationships, ideologies, ideas, attitudes, and habits that form. Homelessness, in my opinion, is the phenomenon of people taking each other for granted and underestimating the severity of traumatic events in order to maintain some semblance of normalcy; for those who are not in dire straits relative to those sleeping outside, it is the unforgiving obverse of humility associated with exalting one’s own development at the expense of the other person. Georgia State’s new mission for achieving its Strategic Plan is setting the standard for using humility, along with structured incremental plans, in order to empower our community to share more stories of redemption.

Since Rome was not built in a day, addressing the needs of college students experiencing homelessness, the foster care system, and economic and familial hardships must be a comprehensive and multi-pronged system that can potentially test the patience and mettle of everyone choosing to embark on this journey. But I think that this journey is well worth it because there is a certain propensity for humility, pride, and grit that must accompany an undertaking of this magnitude. Someone on the Georgia State campus, regardless of whether that person is a student or not, is suffering from the totality of internal and external forces resulting in the relegation to second- or third-class citizenship as you read this. One must ask—and I definitely implore the reader to do so!—whether that is a part (if not the primary component) of the legacy that he or she wants to develop as a member of the Georgia State community. Who are we to reap the vast benefits of this institution while withholding the same from our peers? Who are we to look down upon them as if they do not have the wherewithal to help us in both the short term and the long term—as if their knowledge and experiences are obsolete? Some sections of Georgia State’s faculty and staff are at the preliminary stages of discovering displaced students. Recognizing the problem and participation from multiple parties throughout campus are paramount if there is any hope of alleviating this societal ill. I am confident that, given the crossroads that our institution is facing, there are enough humble, considerate, and driven members in this community who do not merely want to uphold the status quo, but set the tone for a groundbreaking social, economic, scientific, and political cause. Together, we can get there; apart, we will fall asunder, contemplating the errors we made and wondering “What happened?”