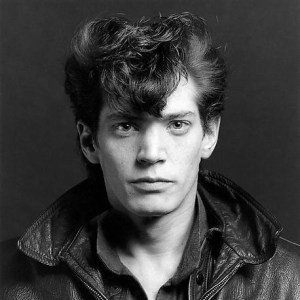

New York man Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–1989) wanted to do one thing with his life: to live for art.

During his teens and early twenties, he experimented with drawing, painting and sculpture.

Then, in 1970 a friend gave Robert a loan of a 360 Land camera, a clunky but technically simple, silver and black device. Robert settled on the camera as his creative tool of expression because “it was more honest.”

At first, Robert restricted himself to only taking pictures of his former -girlfriend and life-long creative partner the singer Patti Smith. The confines of a single muse shaped his creative vision and enabled him to hone his technique.

In Just Kids, Patti writes:

“He was comfortable with me and he needed time to get his technique down. The mechanics of the camera were simple, but the options were limited.”

That wasn’t the only restriction Robert faced. In the 1970s, camera film was expensive, and Robert couldn’t afford to make mistakes.

So, he made every shot count.

Robert developed his technique and visual eye with the 360 Land Camera and later a Polaroid. In 1973, he held his first solo photography exhibition at the Light Gallery in New York.

With success, came more financial and creative resources. A patron bought Robert an expensive Hasselblad camera (a type of camera previously used to photograph the moon landings).

Although a professional-grade camera gave Robert more choices and control over his use of light, he didn’t learn anything about the creative process from having access to more powerful tools.

According to Patti, “Robert had already defined his visual vocabulary. The new camera taught him nothing, just allowed him to get exactly what he was looking for.”

What Robert was looking for was to document New York’s S&M scene, and a subsequent exhibition shocked audiences and impressed his peers. He said:

“I don’t like that particular word ‘shocking.’ I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before … I was in a position to take those pictures. I felt an obligation to do them.”

Robert went on to photograph a series of male and female nudes; delicate flower still lives lifes and portraits of artists and celebrities. He also collaborated intensely with the world’s first female bodybuilder Lisa Lyon.

He continued to push photography forward as an art form until he died of AIDS in 1989.

Today, Robert is regarded as one of the twentieth century’s most provocative visual artists, and his work is displayed in galleries around the United States, South America and Europe.

The Creative Power of Constraints

Constraints are liberating.

Creative masters like Robert Mapplethorpe saw chaos around them and brought order to it. What better way to bring order than to restrict yourself to a few chosen tools, a big idea or means of expression.

If you were told you could write, draw, film or paint anything you liked using any material imaginable, it would be difficult to know where to start.

On the other hand, if you were given a creative brief that required you to write 1,000 words about the importance of storytelling or sketch Dublin city at dawn using charcoal, these restrictions would force your brain to come up with more inspired ideas.

You can overcome creative overwhelm by narrowing your choices.

For example, if you don’t have the freedom to work on your ideas for eight hours straight because you have a job or other personal commitments, use the constraint of time to create what’s most important to you first thing in the morning or at night.

Don’t afraid of a looming deadline; use it as a catalyst to drive yourself and your project forwards.

Or if you lack the financial resources to conclude your project, reduce, remove and simplify your work and then finish what you can afford. You can always come back to the unfinished parts of your creative project later on.

What We Can Learn from Robert Mapplethorpe

Creative masters like Robert Mapplethorpe impose constraints on their works rather than seeking out unlimited resources. These constraints helped them learn more about the creative process.

When you have too much freedom, getting started or finishing your work can feel impossible. On the other hand, artificially imposed constraints will help you come up with better ideas and give you an end goal to work towards.

It will narrow your creative vision and help you focus on what’s important.

This is an edited extract from The Power of Creativity: How to Conquer Procrastination, Go Deep Into Your Work and Find Success (Book 3 in a 3-part series)

Originally published at becomeawritertoday.com on January 20, 2017.