Trading in Antiquity

Ancient Greeks frequently set out on trading voyages and captains sought capital in order to finance these excursions. The returns for these early investors were binary: Either the ship returned home or it was lost at sea, along with all of the men as well as the booty the investor would’ve been entitled to a portion of. This high-risk gamble did not dissuade potential financiers, as many saw the possibility of wealth and goods from foreign exchange as a plausible method of enhancing their store or becoming more affluent.

The Romans pursued similar avenues of acquiring capital, not only for their commercial fleets, but also for major construction projects as well. Indeed, one need look no further than the aqueducts or the sprawling road system the Roman Empire was able to construct. While no longer in use, many of those same aqueducts and thoroughfares still exist, a testament to Roman building prowess and the power of group investing and public funding.

The Dutch formed the East India Company in 1600 in order to trade internationally. Rather than investing in single outings, however, the Hollanders were able to purchase stake in the company that financed the voyage itself. Comparatively speaking, news took ages to spread in that age, so speculation was rampant, as even the gauziest of hearsay or rumor could spark marked increases or decreases in the value of a share. This may be the first instance--the ur-- of what we commonly regard as “FUD,” or “fear, uncertainty and doubt,” one of the most-used disinformation techniques.

At the same time the Dutch were installing an enormous seafaring trade network, the English were experimenting with their own form. The East India Company, an English joint-stock venture formed to conduct trade with the East Indies, was formed in 1599 when more than 100 investors pooled £30,133 (contemporary value: approximately £8,460,000, or nearly $10 million in USD) in order to procure a charter from the queen to set out for the Indies much as the Dutch had.

“The names of such persons as have written with their own hands, to venture in the pretended voyage to the East Indies (the which it may please the Lord to prosper), and the sums that they will adventure, the xxii. September 1599, viz.”

Queen Elizabeth I granted the charter almost a year later, and in 1600, the Company was officially formed. The Company was dissolved almost 275 years later and while the original intent was to engage in trade, by the time the Company became defunct, it had aided in establishing the British Empire in India. Incredible wealth was realized from the trade of commodities including textiles, tea, spices and opium. It was not until 12 years after the creation of the Company did it become a joint-stock type, which allowed merchants and investors to trade the stocks of British Companies on an exchange.

Fear, uncertainty and doubt played a large part in these markets as well. There are several notable bad actors who defrauded English investors, and one of these ne’er-do-wells was a Scotsman called John Law, who despite his lengthy roll of financial accomplishments, still managed to defraud investors in Europe by claiming there were great reserves of natural wealth in the New World, namely Louisiana. Despite being a failed gambler and murderer, Law was able to ascend to the position of , having taken advantage of King Louis XIV, who was in dire straits economically after having frittered away France’s once-admired fortunes on his wars and lifestyle. He convinced a weary Louis XIV to back his idea for a national bank, the Banque de Franc, which would issue paper currency rather than the gold and silver coins which were the monetary lingua franca. Despite never becoming a national bank, but instead a private, stockholder-financed bank, the Banque de Franc developed into a central bank with considerable authority.

John Law

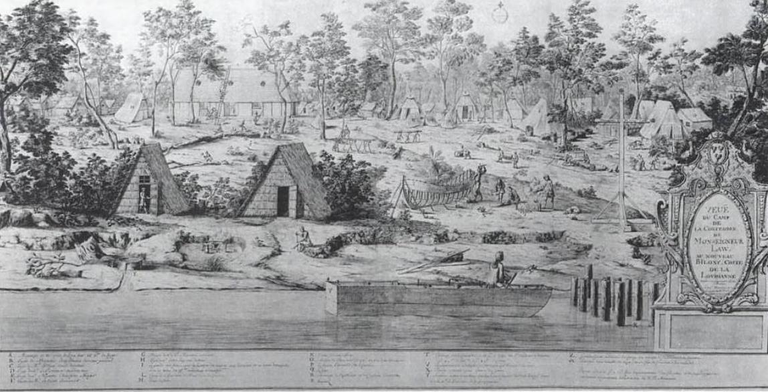

The Mississippi Company was France’s corporate establishment in the West Indies and the New World. A year after his national bank opened, Law was declared the managing director of the Company. As a confidence man, Law was nonpareil: Through beguilement, he managed to amass a great fortune with suggestions of massive, though actually imaginary, stores of wealth in Louisiana, including the pedestrian gold and silver, and up to and including an actual mountain of emeralds. The hysteria was white-hot and short lived and Law died in 1729 after seeing his reputation and his economic and financial machinations laid to waste.

The John Law Camp in Biloxi, 1720.

Even taking into account the roster of scam artists and the declining reputation of the broker, these burgeoning markets and nascent economic practices firmly established Europe as a global financial powerhouse.

A Brief History of The (American) Stock Market

On May 17, 1792, 24 of New York’s most powerful and influential stockbrokers—now affectionately known as the Founding and Subsequent Fathers—convened beneath the boughs of a buttonwood tree on Wall Street, one of New York’s oldest thoroughfares. In that shade, uncovered on the literal street, the first American stock market was beginning to form. These early brokers bought and sold to each other shares in banks and mines. The original document, housed at the New York Stock Exchange Archive, established the early framework for what would be the first iteration of the New York Stock Exchange.

The document was forged mostly in response to the increasing number of people wishing to trade on Wall Street, which the auctioneers saw as a threat, as diluting their small coterie of learned men with interlopers would result in a lessened commission, as well in effort to keep the federal government from establishing oversight on their practices.

The Buttonwood Agreement.

Taking up business across the street in the Tontine Coffee House, the signers of the Buttonwood agreement continued their work behind locked doors. This has a dual effect on the trading public: Not only were they no longer privy to the happenings inside, they could also no longer trade directly, as they were now forced to go through brokers who in turn spoke directly to those inside the Tontine. Conversely, this centralization reduced the spread of hearsay, bringing a calmness to the previously unkempt method of transacting. Additionally, because the system of auctioneering had changed to a more regular, periodic fashion, brokers exercised more restraint in their conduct. Only specific stocks from certain well-established, highly trusted companies and institutions, such as Bank of New York.

This was not the end of the open-air market, however. Street hawking continued despite the formation of the how-housed New York Stock and Exchanges Board, which naturally included the trading of less robust companies by less scrupulous auctioneers and brokers. In spite of this, growth continued apace, thanks to westward expansion and rapid developments in technology, the greatest of those being the microprocessor.

Prior to that invention, however, was another major stepping stone: Samuel Morse’s telegraph. For a quarter dollar, he would show stockbrokers his device, which he had set up outside the exchange. Nests of wires soon covered New York, removing the need for local stock exchanges and cementing its place as the centralized financial capital of the world. The ticker and it’s parade-coupled tape came not too long after, further increasing the speed at which buyers and sellers could acquire useful market information, as well as making this information public knowledge. Lastly, near the end of the 1800s, Charles Dow and Edward Jones began to publish the Wall Street Journal, which included their novel Dow Jones Industrial Average, a fresh way of visualizing the index of specific stocks and delivering a general overview of stock market health. Every invention and movement forward not only allowed for greater insight and understanding of the market’s minutiae, but also gradually reintroduced the public into the idea of stockholding by making it easier to understand and interact with. Regardless of the coming obstacles which again spooked the public--the ‘29 crash, World Wars, etc.--with the arrival of the computer, people were once again friendly toward stocks and shareholding. It had been well understood and taught by this point that markets do fluctuate, and the occasional disaster or demidisaster will transpire, no matter how sophisticated our tech becomes, as the two are not unknown to each other.

Well, How Did We Get Here?

This may well be an era of the reinvigorated retail investor. Billions are estimated to urbanize in the next few decades, and while a sizeable portion of that population already has access to smartphones thanks to technological leapfrogging, the influx of those without and who are eager to participate will generate fantastic sums for those in the fields of advertising and remittance, to name only a couple areas. The United Nations has several ongoing projects dedicated to ways the blockchain can help those in less-developed areas of the world.

The idea of the retail investor—non-professional individuals—is comparatively fresh in the larger scheme of things. Institutional investors are a significantly older breed and have significant influence over the stock markets, as they make more trades more frequently and tend to exert considerable power by way of voting. Additionally, institutional investors can be privy to boardroom discussions and occasionally meet with executives, similar to those privileged enough to have the ear of the early Wall Street barons. Their sway is tremendous and thus retail investor behavior is often similar to that of their institutional peers, as the actions of the institutions indicate whether or not a fund or company is healthy enough to attract massive amounts of capital. Institutional investor maneuvers inform individuals of approved institutional ownership and signals security. Despite advancements in the field of retail investing, foremost being the reduction in fees and widespread availability of online brokerages, institutional ownership remains the prime force in shaping how the market moves and operates.

However, even though the modern ease with which one may become a shareholder, Americans seem to stand by an older understanding of “the markets.” According to Gallup tracking, 55% of households in the United States reported owning stocks. This is a reduction of 7% since the financial crash of 2008. Interestingly, despite the recovery of the markets, fewer Americans have returned to the stocks, though this may change in the future as the markets’ health grows apace.

That figure, however—55%—can be misleading without further data or context. For instance, according to Money.com, (“The Richest 10% of Americans Now Own 84% of All Stocks”) the vast amount of shareholders are the wealthiest citizens. In fact, ownership skews dramatically upward: “Furthermore, while virtually all (94%) of the very rich reported having significant stock holdings—as defined as $10,000 or more in shares—only 27% of the middle class did.” One could contemplate a link between this information and the oft-reported (the figures change over time, slightly, but the message remains clear) analysis that the middle class, in spite of having the means to do so, overwhelmingly fails at saving (The Atlantic: The Secret Shame of Middle-Class Americans: Nearly half of Americans would have trouble finding $400 to pay for an emergency. I’m one of them.). Lifestyle choices and aside, the number of people living paycheck to paycheck while simultaneously earning enough to be labeled “middle class” is curious and appears to sketch a grim portrait of consumer habits.

Investing in the Age of Robinhood

This balancing resulted in expanded opportunities to attain financial self-determination for the less affluent portion of the population at no detriment to those who were already in positions of wealth. By removing roadblocks to those who seek to become retail investors, more money has entered into the system, increasing the market cap while simultaneously providing a way by which communities may be strengthened from bottom up: By providing avenues for the everyman to invest, individuals are who were previously unable to plan for their futures or even save can now develop and use financial strategies for their own life and the life of their family. Additionally, investing tends to teach one to better manage material resources by introducing and bolstering concepts of financial prudence and gratification deferral, two notions frequently absent in poor and lower-class populations. In this way, individuals have an enhanced capability to bootstrap. By elevating oneself, the individual realizes self-determination, which can inspire not only the individual to greater heights in life, but has the additional effect of demonstrating clearly to others that a more vibrant future may lie ahead, if one is able to grasp the nettle.

Similar to the Parable of the Leaven, wherein large wealth comes from small beginnings.

To be clear, this is a form of gaining power over one’s own life, increasing autonomy while alleviating the necessity of relying on others or the state. This is the essence of self-determination: Identifying and understanding available methods of helping oneself and then actually utilizing them and learning from them.

Written by haems of Merkle Talk

Please join our community on Slack!

Congratulations @merkletalkteam! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!