CUBOCTAHEDRON AS A POTENTIAL EVIDENCE OF THE

“CULTURAL BRIDGE” BETWEEN KYOTO AND KAYSERI

Hakan Hisarligil

Meliksah University, Turkey

Keywords: Vector equilibrium, cuboctahedron, R.B. Fuller, Kayseri, Kyoto.

- Introduction

There are several abstract geometrical forms ascribed to have a symbolic meaning in various

cultures through history. Among these cuboctahedron, one of 13 Archimedean solids has

been an interest of art and religion in Japan in the past [1]. Recently the existence of

cuboctahedron discovered in other cities and countries on the “Silk Road” also leads to

question whether they represent similar content as well [2]. However the examples here in

this short text are to be limited to the ones discovered in downtown Kayseri belonging to the

13th century. Thus, following the trace of cuboctahedron, we will try to demonstrate the

potential evidences of cultural affiliation between two cities of remote geographies through

this study. - A Brief Outlook to Cuboctahedron

2.1. Cuboctahedron "By Any Other Name"

The cuboctahedron is named thusly because it is simply an intersection of a cube and an

octahedron, as represented in the "Crystal" by M.C. Escher in 1947 [3]. Associating the

episode "By Any Other Name" of Star Trek TV series (Fig. 1), where aliens seize the

Enterprise by transforming crew members into inanimate cuboctahedron [4], it is attributed

numerous names in geometry such as triangular gyrobicupola, cantellated tetrahedron,

rectified cube and heptaparallelohedron. Buckminster Fuller applied the name "Dymaxion" to

this shape along with “Vector Equilibrium” [5]. Further, in “sacred geometry” this shape is

known as “Heart Sphere” or “Terra Prana Sphere”, since it represents both the earth (cube),

and air/prana (octahedron), implying the perfect synthesis for just about everything [6].

Fig. 1: Left: Mezzotint "Crystal" by M.C. Escher, 1947, Right: "By Any Other Name ", Star Trek

2.2. Cuboctahedron through History

The first appearance of cuboctahedron is in the book titled as “Archimedean Solids”, which

Pappus of Alexandria lists solids and attributes to Archimedes, though Archimedes makes no

Archi-Cultural Translations through the Silk Road

2nd International Conference, Mukogawa Women’s Univ., Nishinomiya, Japan, July 14-16, 2012

Proceedings

21

mention of these solids in any of his works [7]. Long after, it reappears in Luca Pacioli's book

“De divina proportione” written around 1497 where all figures are drawn by Leonardo da

Vinci [8]. Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) was the next to write about the Archimedean solids

collectively in his book “Harmonices Mundi” [9]. In 1950, Dr. Derald Langham, agricultural

geneticist and author of “Circle Gardening”, developed the “Genesa Concept” [10]. He

believed that Genesa crystal is a sacred geometric shape called cuboctahedron that uniquely

contains within it all of the five platonic solids that are the building blocks for all organic life.

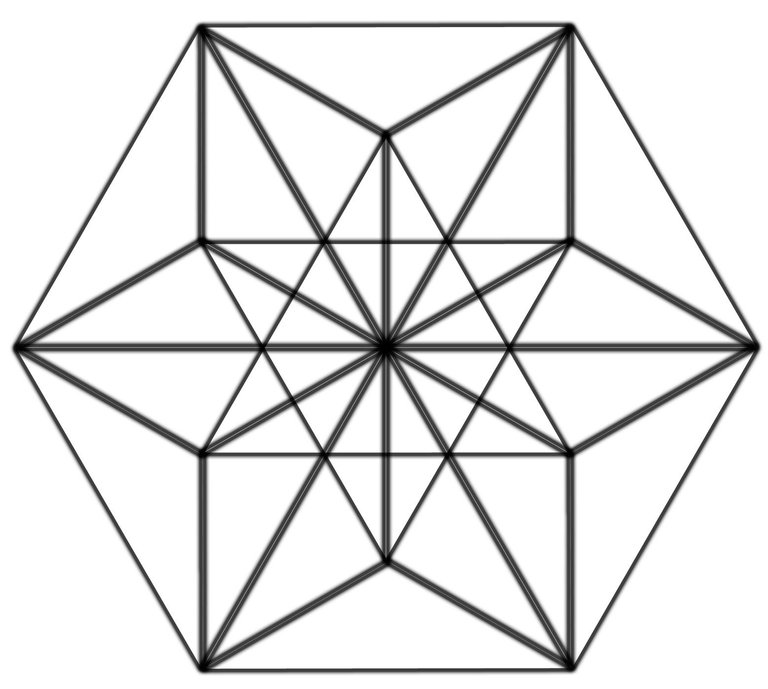

Cuboctahedron is at the center of Buckminster Fuller’s philosophy. Fuller calls this shape the

“Vector Equilibrium” meaning as the dynamic balance of tensional cosmic forces, since,

unlike Cartesian coordinate system, it can strikingly be developed around one nuclear sphere

[11]. Equilibrium of this kind is also called ‘isotropic vector matrix’ as an omnidirectional

closest packing around a nucleus about which omnidirectional concentric closest packing of

equal spheres about form series of vector equilibria of progressively higher frequencies (Fig.

2). Following Fuller, the physicist Nassim Haramein in his unified field theory suggests that

the structure of space-time is a cuboctahedral "vector equilibrium". According to his theory,

the structure can be seen in the close-packed hexagonal cells of honeycombs and bubbles,

boiling water, and the storms on gas giants [12].

Fig. 2: Cuboctahedron through history Left: Pappus, Middle: Leonardo da Vinci, Right: Fuller - Cuboctahedron in Kyoto and in Kayseri

3.1. Cuboctahedron in Kyoto

Cuboctahedron seems to have had a special meaning for religious people in Japan. It is still

open to discussion that in the past the most revered solid symbol was not the cuboctahedron

but the Hoju gem, a chest-nut shaped solid. It is known that it had been widely used as

decorations in furniture and buildings in Japan in the past, since cuboctahedral decorations

can easily be made and practically used. Lamps called Kiriko, in the shape of cuboctahedra

were appeared as a lantern in pictures as early as 13th century and they are still used today

in certain religious ceremonies in memory of the dead (Fig. 3) [13]. Besides, numerous

examples of Hoju may found in the sanctuary of a shrine or a temple. In particular, a big Hoju

usually is put on the top of the Gorinto pagoda, a five storied small pagoda, which is the most

typical monument for the Buddhist in Japan (Fig. 3). This pagoda is made of five blocks

which symbolizes the earth (a cube), water (a sphere), fire (a square pyramid or sometimes a

tedrahedron), air (a hemisphere), and the universe (a Hoju), from bottom to top [14]. There is

an opinion that such construction might be derived from Plato’s book entitled “Timaeus”. If it

is so, the Hoju represents the regular dodecahedral universe of Plato (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Left: Kiriko lanterns in a Bon ceremony Middle: Pagoda Right: “Hoju” gem

22

Symbolizing the God, it also forms the decoration or monuments such as pagoda, the main

hall of a temple or shrine (Fig. 4) or at the top of sacred buildings (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4: A cuboctahedral sacred offering completed in the middle of the 17th century,

tomb of Tokugawa leyasu, Nikko

Fig. 5: Cuboctahedral top decorations on Imperial monuments (tea house) in

Shugakuin Imperial Palace, Kyoto

Hargittai has also reported that there are some cuboctahedral top decorations on garden

lantern (“Toro” in Japanese) in Shugakuin Imperial Palace in Kyoto (Fig. 6) [15].

Fig. 6: Cuboctahedron examples on top of a garden lantern in the Shugakuin Imperial Villa in Kyoto

3.2. Cuboctahedron in Kayseri

The first Turkish contact with the political power in Islam was in the 11th century at the hands

of the Seljuks. Among the many Turkish States and cultures formed throughout history, the

Seljuks have a very significant place and their art represents an important milestone within

Turkish art [16]. Involving common specific features of Islamic art and architecture in general,

numerous works of Seljuk Turks in Anatolia represent abstract geometrical dimension of the

Muslim World particularly. According to Rabah Saoud, the artists of that era used and

developed geometrical art for two main reasons: “The first reason is that it provided an

alternative to the prohibited depiction of living creatures. Abstract geometrical forms were

particularly favored in mosques because they encourage spiritual contemplation, in contrast

to portrayals of living creatures, which divert attention to the desires of creatures rather than

the will of God. Thus geometry became central to the art of the Muslim World, allowing artists

to free their imagination and creativity. A new form of art, based wholly on mathematical

shapes and forms, such as circles, squares and triangles, emerged. The second reason for

23

the evolution of geometrical art was the sophistication and popularity of the science of

geometry in the Muslim world. They also show that early Muslim craftsmen developed

theoretical rules for the use of aesthetic geometry, denying the claims of some Orientalists

that Islamic geometrical art was developed by accident (e.g. H. Saladin 1899)” [17]. Indeed,

the recently discovered Topkapi Scrolls by Gulru Necipoglu [18], dating from the 15th century,

illustrate the systematic use of geometry by Muslim artists and architects. Further, showing

how mathematicians instructed artisans, Alpay Ozdural provides us with an insight into the

explicit collaboration between mathematicians and artisans in the Muslim World [19].

Remarkable works on Seljuk art (Makovicky, 1992; Alexander, 1993; Lu & Steinhardt, 2007)

[20] also conclude and suggest that artisans of the era had an intuitive understanding of

highly complex mathematical problems. Likewise, the recent discovery of numerous

examples of cuboctahedron of 13th century in Kayseri in 2009 [21], also indicates such a

complex geometrical content of the art of the era. In fact, cuboctahedron is a quite common

figure in iron window grills of the buildings of both Seljuk and Ottoman era in Turkey. Further,

the base of almost all kumbets also implies almost an upper part of a cuboctahedron on the

ground surface (Fig. 7). However, there has been found no written record indicating their

existence and possible meaning so far.

Fig. 7: Cuboctahedron on kumbets and iron window grills

Hence, demonstrating the examples discovered in Kayseri, numerous possible meaning will

be attributed to cuboctahedron under the guidance of extensive explanations on

cuboctahedron in “Synergetics” by R.B. Fuller who is putting cuboctahedron at the top of the

cosmic hierarchy as center of creation. The first one is if the cuboctahedron replaced by

some other forms of capital of colonnade such as ‘tree of life’ and ‘muqarnas’ represent

cosmos, humanity or the entire creation with the creator veiled (Fig. 8). Second whether the

niche in the form of cube enclosing almost all examples represents the location of eternal

energy as described by the God in the “Al-Noor” (The Light) verse of holy Quran [22].

Fig. 8: Left: Examples of cuboctahedron enclosed by a niche in the form of cube Right: examples of

‘tree of life’ and muqarnas replacing cuboctahedron

Bearing in mind that octahedron represents “air” and cube represents “earth” for Plato,

cuboctahedron placed in the middle of the arches of main portals associates the balance as

the worldly creatures between ‘earth and sky’ (Fig. 9) [23]. If so, beside this vertical balance,

the animal figures placed on the cuboctahedron, a bird on the left and a lion on the right, at

the main portal of Karatay Caravanserai, would virtually represent the Yin-Yang as the

24

‘harmony of opposites’ common both to Eastern and to Western philosophy since ancient

times (Fig. 9) [24].

Fig. 9: Left: Location of cuboctahedron at main portals, Right: Cuboctahedron with animal figures at

Karatay Caravanserai

Further, the octahedron discovered at the main portal of Kilij Aslan Mosque leads us to think

whether the artisans of 13th century have already had the idea of “jitterbug” representing the

phase transformation between cuboctahedron and octahedron as visioned by Fuller at the

end of 20th century (Fig. 10) [25].

Fig. 10: “Jitterbug” representing the phase transformation between cuboctahedron and octahedron

- Discussion and Conclusion

After having observed the examples presented above, any one clearly trace that two cities of

remote geographies, Kayseri and Kyoto, had explicitly shared something common in the

past: Cuboctahedron. Regardless the differences in terms of size, position and material etc.

between the examples, they are somehow a form of a secret manifestation of Japanese and

Turkish designers practicing for either sacred or practical purpose. The examples of

cuboctahedron of both cultures in their unknown meaning and context can be regarded as

not only as the evidence of cultural affiliation between two locations but further as the road

map of guiding throughout both ends of the “Silk Road”. However, having discovered

numerous other examples in other cities and countries, it is obvious that this limited survey is

far from covering the subject and geography it deserves. Our hope is that, by drawing the

attention of scholarly circles on that relatively new and exciting content, the cuboctahedron

will lead a series of colorful researches bridging the East and the West as it was in the past.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.mukogawa-u.ac.jp/~iasu2012/pdf/iaSU2012_Proceedings_102.pdf