The 6 Songs Billy Graham Picked for His Funeral

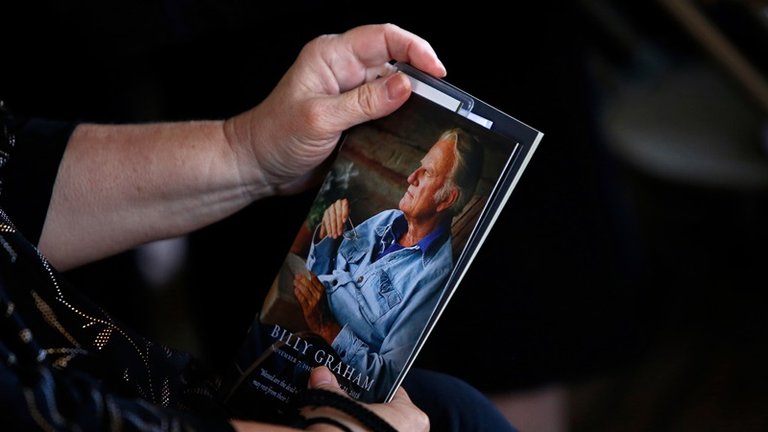

Billy Graham is laid to rest in North Carolina today, the 2,000 invited funeral attendees will listen to—or sing together—six songs. Graham, who planned his own funeral [see CT’s live report], was the one who chose them.

In this, he seems to have taken the path of his longtime music director Cliff Barrows.

“I want a lot of music,” Barrows instructed Billy Graham Evangelistic Association choir director Tom Bledsoe before he died in 2016. “And I want the people to sing.”

Graham’s six picks:

“Until Then” (Stuart Hamblen, 1958), performed by musical artist Linda McCrary-Fisher

“All Hail the Power of Jesus’ Name” (Edward Perronet, 1779), congregational singing led by Bledsoe

“Above All” (Lenny LeBlanc and Paul Baloche, 1999), performed by musical artist Michael W. Smith

“Because He Lives” (Bill and Gloria Gaither, 1970), performed by the Gaither Vocal Band

“To God Be the Glory” (Fanny Crosby/William Howard Doane, 1875), congregational singing led by Bledsoe

“Amazing Grace,” bagpipe escort led by Pipe Major William Boetticher

CT asked worship and hymnody experts what they thought of Graham’s choices:

John Witvliet, director of the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship and professor of worship, theology, and congregational and ministry studies at Calvin College and Calvin Theological Seminary:

Each of these songs echoes central themes in Graham’s ministry: All glory be to Jesus, whose death and resurrection set us free from sin. There is also a steady focus here on life with Jesus in heaven, a hallmark of evangelical piety, a strong emphasis on one’s own individual and personal affirmation of faith, and a warmth of affection.

Notably, this set of songs also embraces both older and newer expressions. “Above All” wasn’t written until Graham was 80. It’s not often that people select songs for their funeral that they didn’t know until late in life.

Mark Noll, research professor of history at Regent College; emeritus Francis A. McAnaney Professor of History at the University of Notre Dame:

This list looks like something from one of the hymn pamphlets prepared by Cliff Barrows for a typical Graham crusade from the 1950s or ’60s, with slight modifications tilted toward the contemporary. Such pamphlets, in turn, resembled the way that Ira Sankey prepared his “Sacred Songs and Solos” from his musical work for D. L. Moody.

Sankey and Barrows, both fond of traditional hymnody but also very much in tune with the times, followed similar paths. They put to use “classics” that could be sung with enthusiasm and gusto (e.g., “All Hail the Power of Jesus’ Name”). They found contemporary hymns that their own promotion made into classics, as Sankey did for several of Fanny Crosy’s compositions (“To God Be the Glory”). They featured music popular among the constituencies that came out to hear Moody or Graham and went away warmed in their hearts (“Because He Lives,” “Above All”).

https://info.echurchgiving.com/lp-2017-03-checklist-Retaining-Easter-Guests.html?utm_source=christianity-today&utm_medium=display-paid&utm_campaign=easter-checklist&utm_term=faith--all--all--300x250&utm_content=content-ebook

They made especially good use of songs tied to the ministry of the evangelist, as the BGEA did for so long with George Beverly Shea and “How Great Thou Art” (for the funeral, “Until Then,” which I am remembering as sung on one of the Graham movies of the 1950s, but maybe I’m imagining). And with “Amazing Grace,” they take a hymn well known to many people, but with the bagpipes presented it in a form that had become super common (because, in this case, of how often bagpipe renditions were used at memorials after 9/11).

W. David O. Taylor, assistant professor of theology and culture at Fuller Theological Seminary:

There’s very little surprising in this selection of songs, but that may be just to state the obvious. This is Billy Graham, after all. His musical preferences have been a matter of public record.

All six songs represent conservative evangelicalism in its most typical (free-church? low church?) form. These are, typologically, songs of adoration and acclamation.

We have a representative of 19th-century revivalism: Fanny Crosby.

We have a contemporary of the Wesley brothers: Edward Perronet.

We have the poster child for 20th-century gospel music (Gloria Gaither) and one of radio’s first singing cowboys (Stuart Hamblen).

Lenny LeBlanc’s “Above All” may be the surprise choice. This is not because Graham was unfamiliar with more “contemporary” worship music—he was a close friend of Fernando Ortega and Michael W. Smith, among others. It is because the feel of the song, “Above All,” is unlike the more “classic” evangelical hymn. It’s still a praise song, so it fits.

A line in the hymn “Until Then” says, “This troubled world is not my final home.” That may have been the case for Graham, who is now in his true home, but he loved this world as God so loved it, and he loved the way musicians could give voice to creation’s praise as an anticipation of that final, definitive praise of the new heavens and the new earth.

Greg Scheer, composer, author, speaker, and a music associate at the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship:

In a real sense, the story of 20th-century evangelicalism is the story of Billy Graham. Similarly, the songs Graham chose for his funeral provide a window into the heart of evangelical worship.

“To God Be the Glory” and “Because He Lives” bookend the sweet spot of evangelical hymnody: Fanny Crosby’s song is a classic example of the gospel hymn genre that was synonymous with the 19th-century revivals that birthed evangelicalism, while Bill Gaither’s song is a 20th-century hit of the same lineage.

Evangelicals have never been shy about borrowing from pop culture for the sake of the gospel; Graham’s choice of “Above All” is quintessential evangelicalism, combining a modern music style with a sentiment of personal faith.

The immediacy of heartfelt modern songs may be at the core of evangelical identity, but at times it reaches back into the broader history of Christianity; we see this in “All Hail the Power of Jesus’ Name.”

Finally, in Graham’s choice of an African American singer, Linda McCrary-Fisher, we see mirrored an evangelical desire for the gospel to reach across lines of race, despite (white evangelical) America’s troubled racial history.

Perhaps what is most remarkable about Graham’s final worship service is how entirely unremarkable it is: These are songs that might appear in this Sunday's “blended” service at any church in America.

Wen Reagan, director of worship at All Saints Church in Durham, North Carolina, and instructor of church history and worship at Duke Divinity School:

In so many ways, these songs are classic Billy Graham.

Stuart Hamblen, a Hollywood cowboy who came to faith at a Graham crusade in 1949 and whose conversion served as a turning point for Graham’s ministry, painted a classic evangelical theme in “Until Then”—that tension between the already and the not yet, the juxtaposition of worldly trials and tribulations with the coming resolution and bliss of union with Christ in the world to come.

This theme is then echoed in the Gaithers’ “Because He Lives,” which has become an evangelical classic over the last 50 years and which the Gaithers performed at several Graham crusades. And according to Bill Gaither’s autobiography, “Because He Lives” was Billy’s favorite song (likely one among many).

“All Hail the Power of Jesus Name,” the towering 18th-century hymn, introduces another theme that was so common in Graham’s ministry: the lordship of Christ. Whether fighting communism in the 1950s or utilizing media technologies to spread the gospel, the lordship of Christ over all arenas of life flowed throughout Graham’s message.

This theme then flows on into Paul Baloche’s “Above All,” where Christ is lifted “above all powers, above all kings.” Yet, just as Graham did in his crusades, the Christus Victor is always brought back to the evangelical mainstay of substitutionary atonement, with a deep emphasis on God’s love and concern for you and me: “Like a rose trampled on the ground / You took the fall / And thought of me / Above all.” Whether or not that last line is too anthropocentric for the theologically sensitive, it certainly rings true as a heartsong of American evangelicalism and the Graham crusades that fueled it in the late 20th century.

Then Fanny Crosby’s 19th-century classic “To God Be the Glory” sings forth another mainstay of Graham crusades: the gospel of love, rooted in John 3:16. The song itself holds a special place in the history of Graham’s ministry. Graham’s longtime musical partner, Cliff Barrows, was first introduced to Crosby’s hymn in the mid-1950s, and Graham’s crusades were basically responsible for a resurgence in popularity for what had been a mostly forgotten song (at least in America). It also served as the closing hymn for the dedication of the Billy Graham Library in 2007.

While I imagine each of these songs held a special place in Graham’s heart, they also resound the topical passions of his storied ministry and the impact it had on American evangelicals.

Good research bro. Very informative article.

Simplly n fully describe a lot of about the great person