As heavily as the damage humanity has wrought upon the oceans has changed the course of evolution, the damage on land has done even more to shift the path of evolution. (I really should have done this article second and the article on new species third, but I was really just way, way too excited about the London Underground Mosquito to hold off writing about it. Well, not about the mosquito itself, but its evolution and speciation, at least.) There's a simple reason for why we've altered evolution more heavily on land than at sea- we live on land, and our impacts upon terrestrial biospheres are accordingly larger.

We've forced the Earth into a new mass extinction- over 10% of all existing species are liable to go extinct within the century, making this the sixth worst mass extinction in geological history. (Though it's nowhere near the big 5 mass extinctions yet.) The amount of adaptation that has to be made in order to survive human caused evolutionary pressures is massive. It's critically altered both the makeup of the global ecosystem and the courses of evolution for individual species- not that the two are that readily separable. (If you're interested in reading more about this mass extinction event, I have a whole series on it.)

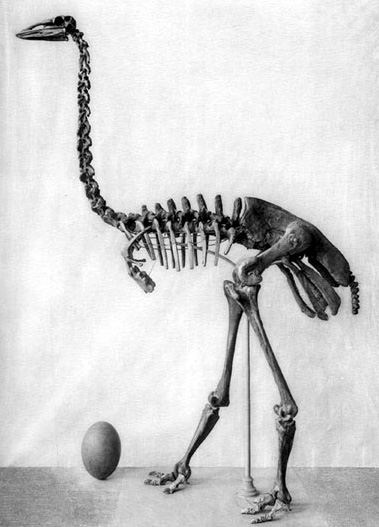

The Elephant Bird of Madagascar. This bird, most closely related to the tiny kiwi birds of New Zealand, grew up to 10 feet tall, weighing in at over half a ton. The species had been driven extinct by the 17th century. It's commonly thought to have been the basis for the legend of the roc, the mythical giant bird from the Thousand and One Nights. The extinction of the elephant bird has resulted in a number of Madagascar fruit trees being threatened with extinction as well- their huge, nearly impenetrable fruit evolved to be dispersed via the bird through its digestive tract, and the species are no longer able to spread themselves over long distances. [Image source]

One major way we've altered evolution? One of the most effective survival strategies is avoiding humans. For macroscopic animals, encounters with humans are extremely risky- it's as likely to result in death as not. Not just via hunting- vehicular traffic is a leading cause of death for animals. Human structures, like power lines, can also frequently be deadly to animals. The bigger an animal is, the more true this tends to be. So more and more adaptations are oriented around helping animals avoid people.

One of the most notable strategies for avoiding humans? Going nocturnal. More and more species are moving their schedule into the night to avoid us. It's a sensible strategy- humans aren't, for the most part, that active at night. This isn't, for the most part, diurnal species becoming nocturnal- instead, it's more flexible species choosing to spend more time awake at night. Coyotes are one major example of this- they've become steadily more active at night than in the day. Given coyotes relative success compared to other predators at surviving around humans, this is applying disproportionate pressure onto many species. Tigers and elephants, to name to other notable species, have been turning more and more nocturnal as well.

Coyotes are better adapted than most large predators to surviving alongside humans- their shift to more nocturnal lifestyles is a big part of that. [Image source]

Going nocturnal isn't a necessarily bad thing, unlike many of the changes we've forced on the planet. It's actually a really effective strategy for evading humans, which is conducive to species long term survival. It's the ecological consequences that are harder to predict, and are accordingly more worrisome. As a critical consequence of this shift in behavior, newly nocturnal predators are hunting more and more nocturnal prey- potentially drastically altering the ecosystems around them. Moreover, if these pressures remain on these species, this nocturnal transition is liable to become permanent. A world where most animal activity on land happens at night is, weird as it is, entirely possible.

The next big evolutionary change? Poison resistance. Everyone's heard of antibiotic resistant diseases, and they're definitely more than terrifying enough. They pose a very serious threat to us, but they're far from the only organisms adapting to poisons we try and use on them. Essentially every single fungicide has resulted in the breeding of new, resistant strains of plant infecting fungi. Pesticides are breeding poison proof insects. Herbicides are breeding plants that can shrug them off like rain. (Over a hundred weeds are known to be resistant to one or more herbicides.) Even organisms as large and complex as rats are evolving like this- rats around the world have developed resistances to warfarin and other rat poisons, and look to be developing them to newer rat poisons like super warfarin.

On top of developing resistance to rat poisons, rats are developing an eating habit known as neophobia- essentially, they're extremely cautious about trying new foods, while rats living farther from humans are always excited to try new foods. This is making them even harder to poison. Rattus rattus, the black rat, is generally considered to be the worst invasive species on the planet, being present all over the globe- they do really well at traveling with humans. They also spread disease and do massive ecological damage everywhere they go. [Image source]

It's not just our deliberate poisoning shifting evolution, however. All of those environmental toxins we're always releasing into nature are causing major adaptations. Even PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), some of the scariest industrial chemicals ever used by humans, are resulting in organisms (mostly fish) with PCB resistance. Essentially, any toxin we release into nature will eventually result in the development of resistant organisms. This is because more powerful environmental stimuli force evolution to work faster. This does NOT, however, give us carte blance to continue releasing toxins willy nilly into nature- resistance does not mean immunity, and it can cause immense suffering in species. In addition, the evolutionary arms race between our toxins and a species resistance is not guaranteed by any means to fall in their favor. Organisms with large, dispersed populations who reproduce rapidly and with many offspring are far more likely to evolve to survive toxins than longer lived, slower reproducing species.

As a matter of fact, that last bit is generally a good rule of thumb. Organisms that reproduce rapidly and with large offspring tend to, more often than not, survive human environmental depredations better. Normally there are many more tradeoffs to both strategies (fewer, larger offspring vs more, smaller offspring), but we've badly altered that balance.

An African elephant. Elephants are a classic example of a species that focuses on having fewer, larger offspring and then investing massive amounts of energy into them. They're one of the major species starting to shift to nocturnal lifestyles. Elephants are also evolving to have smaller tusks, and many more elephants are actually being born that lack tusks entirely, since we hunt them for their tusks so much. [Image source]

One of the most critical ways we're altering evolution, however, is by the way we're altering ecosystems. Cutting down forests forces species to adapt to new, treeless environments, develop methods to travel to areas that remain wooded, or perish. The sheer amount of landscape that we've paved is also a colossal ecosystem alteration. In the United States alone, there are over 4 million miles of road. 14%- nearly 23,000 kilometers- of the US coastline is coated in concrete. (This is done to shield fragile coastal properties, but has the unfortunate side effect of causing waves to erode nearby beaches and coastal marshes much more quickly.)

This adds up to an area the size of Ohio being paved over in the United States alone. This is a huge new biome, and it's really not a friendly one to life. Some species are finding ways to get by on concrete, but not a lot- hence the relative paucity of life in places like Los Angeles, which is 14% parking lot. (You could fit all of San Francisco in LA's parking lots.) The fact that giant metal death machines are moving over all that concrete at high speeds makes them even more inhospitable, as do all the toxins released by the same said death machines. (When it rains, said toxins run off en masse into nearby watersheds, killing countless marine organisms.) All of this pavement is resulting in some radical adaptations. Plants in cities, for example, are evolving to have larger seeds that don't travel very far from the mother plant- they're unlikely to find soil to grow in away from their parent. Birds are evolving to better survive in the dangerous, angular, and loud environs of the city- among other things, birds are evolving to be much louder than they used to be, so they can still attract mates over the noise of traffic and crowds.

I-405 in LA is essentially an impassible barrier to wildlife, whether plant or animal. Even apart from the area covered by interstates, they tend to split other ecosystems apart. The biological carrying capacities of ecosystems are not linearly related to their size- a geographically larger ecosystem can harbor vastly disproportionately larger species populations and greater biodiversity, so roads have ecological impacts far beyond their geological sizes. [Image source]

Humanity has completely and utterly warped the shape of the biosphere. Surviving it is a nightmarish challenge, and many species just aren't accomplishing it. Heck, we've wiped out most wild mammals- the overwhelming majority of the world's mammals by biomass is now made up of humans and their domesticated animals. We and our domesticated animals now outweigh all non-fish vertebrates combined. (Arthropods still have us beat.) We've reduced global vertebrate biomass by seven times on land and even more in the sea. (The reason fish are still ahead of us is that there's just so much sea out there.) 70% of the birds on the planet by biomass are chickens. We've turned Earth into a hellishly tough neighborhood, and anything that wants to survive has got to learn to keep its head down- because it's not looking like anything else is going to get tough enough to stand up to us anytime soon.

Bibliography:

- Door to Door, by Edward Humes

- The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, by Elizabeth Kolbert

- The Song of the Dodo, by David Quammen

- Paving Paradise: The Peril of Impervious Surfaces

- http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2018/05/15/1711842115

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/15/science/animals-human-nocturnal-study.html

- http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/08/fourteen-percent-us-coastline-covered-concrete

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-humans-shape-evolution-other-species/

- https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn20422-unnatural-selection-wily-weeds-outwit-herbicides/

- https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21028101-800-unnatural-selection-how-humans-are-driving-evolution/

- https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21028101-900-unnatural-selection-hunting-down-elephants-tusks/

- https://www.fastcompany.com/3039983/these-beautiful-maps-show-how-much-of-the-us-is-paved-over

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rat

Hey @mountainwashere. Your posts are getting better and better. This one is very interesting (as usual), perhaps even more interesting than mosquito evolution in the tube (mind the gap!). What are the main challenges that we pose on ecosystems through our development? More concrete jungle?

We do, through our construction cut ecosystems up. Highways are bad for this. They help us, move our bodies and good around rapidly but fully agree that they divide up zones and may transit, especially for land animals difficult to impossible.

While reading this, I kept thinking of the cool wildlife underpasses in near Banff in the Canadian Rockies (photo 1). So figured I would post them here in case you or your followers wanted additional insight to a potential solution to one of the problems and challenges you posed.

Photo 1 - this moose is cruising under the highway and doesn't have to face rush hour Source

One solution but of course, would be interesting to know what the research says about how well it works.

I like the other alternative for connection divided populations which is the overpass (Photo 2, Reference 1)

Photo 2. Looks like a nice place to cross. Photo source

Anyway food for thought, and really cool article. What can developing areas or nations do to build these solutions in at the front end during the design phase as opposed to retro-fitting to help fix this problem?

I may post a version of this reply on my blog too as it is getting a bit long...

Reference:

PS. Looking forward to part 4!

Those wildlife crossings are great! Colorado has started putting them in along some highways, which is definitely needed.

I think you should totally just write an article on this yourself, I think you could produce an excellent one!

Thanks for your support @mountainwashere and inspiration. Your series are getting the wheels moving.

Cool. Do you have any photos? Nice to know that these are popping up all over! A great initiative and nice to meet you @colinhoward!

Louder birds, tuskless elephants, rats with +6 poison resistance!?!

Great work on collating all these fascinating examples.

This post has been voted on by the steemstem curation team and voting trail.

There is more to SteemSTEM than just writing posts, check here for some more tips on being a community member. You can also join our discord here to get to know the rest of the community!

Hi @mountainwashere!

Your post was upvoted by utopian.io in cooperation with steemstem - supporting knowledge, innovation and technological advancement on the Steem Blockchain.

Contribute to Open Source with utopian.io

Learn how to contribute on our website and join the new open source economy.

Want to chat? Join the Utopian Community on Discord https://discord.gg/h52nFrV

Congratulations! This post has been chosen as one of the daily Whistle Stops for The STEEM Engine!

You can see your post's place along the track here: The Daily Whistle Stops, Issue 208 (7/27/18)

The STEEM Engine is an initiative dedicated to promoting meaningful engagement across Steemit. Find out more about us and join us today.

Hello, i just upvoted your post. Also, $10 - $160 Reward is waiting for you in GBYTE crypto, please

follow instructions in this post:

https://steemit.com/steemit/@cryptomonitor/airdrop-how-to-claim-tutorial-byteball-bytes-airdrop-to-steemians-hot .

Join our Discord & enjoy happy STEEM community: https://discord.gg/qQZ7Eng