This post is by no means going to be comprehensive. I am certainly not up to the task of developing a comprehensive theory of the business cycle. That task must be left up to someone else. I just want to point out some of what is right about various theories of the business cycle and how many existing business cycle theories are actually complementary. Recessions do not have a single cause. There are many different factors at play. Various thinkers have focused on various aspects of booms and busts but no one has really zoomed out and taken an aerial photo of the whole thing. I believe that we need to integrate the insights of various economic theorists into one single comprehensive business cycle theory.

Here is a brief outline of some of what I think various economists have gotten right:

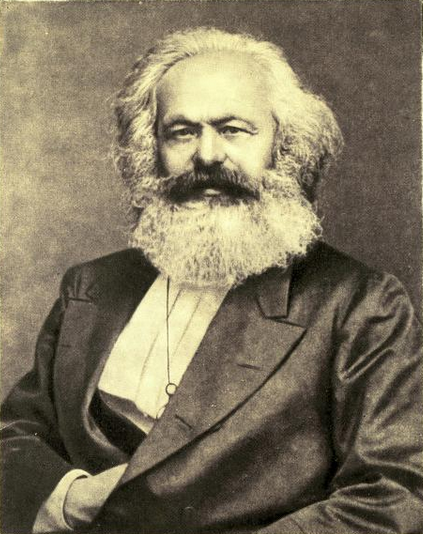

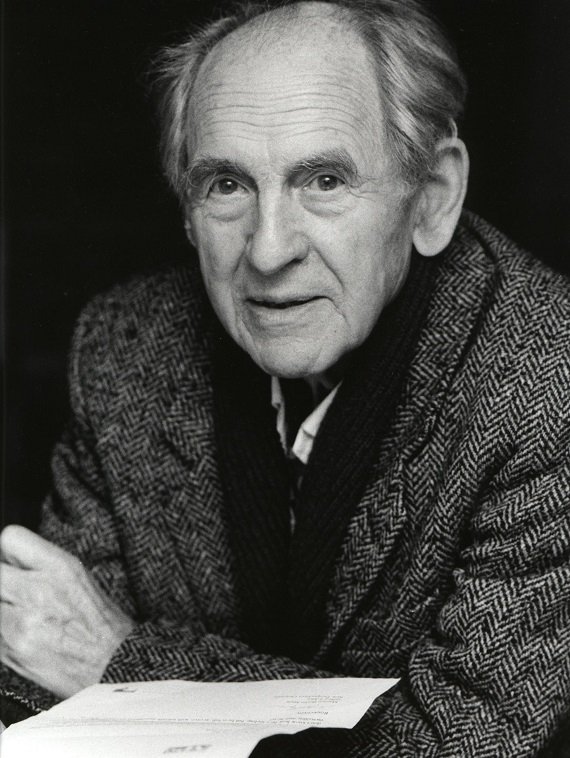

Marx

Karl Marx held that business cycles are caused by the anarchy of production. Capitalism is a market system with private-ownership of industry and without central planning of the economy. Private commodity producers have no way of knowing the actual needs of society, nor do they have any way of knowing how much of that need is being met by others who are producing the same commodity. There is no way for a producer to know exactly how much of his product he ought to be producing. This leads to a tendency to overproduce, which creates a disequilibrium of supply and demand.

Furthermore, capitalists are driven by the motive to maximize profits. Consequently, they tend to pay their employees the least amount that they can get away with (i.e. the least amount that the market and the government will allow). However, the workers are also consumers. The consumers who buy the commodities produced by industry are also workers. Since capitalism and the profit motive encourage employers to pay their workers the lowest possible wages that they can get away with, this means that sometimes the workers in the aggregate will not earn enough money to purchase all the commodities produced—“aggregate demand” will not be enough to clear markets simply because workers can’t afford to buy up the supply. If the workers can’t purchase everything that is produced to be sold, there will be a “general glut” (i.e. a situation in which more commodities are produced than can be sold). Thus, this is just another way that a disequilibrium of supply and demand can naturally occur.

If many producers miscalculate and overproduce or if wages in general are too low for people to be able to purchase the commodities supplied, there will be a “general glut” and a recession.

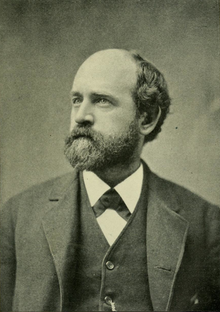

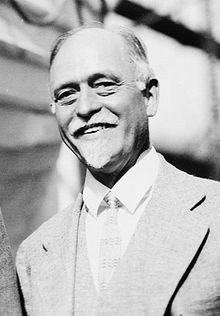

George

Henry George argued that land drives the business cycle. During the boom, speculators anticipate a rise in land prices. This speculation drives up land prices. Widespread speculation will create a situation in which producers cannot turn a profit after paying their rent/mortgage, so production starts to slow down. They lay off workers. Since workers are also consumers, aggregate demand decreases and a recession sets in.

Hayek

F. A. Hayek observed that artificially low interest rates encourage malinvestment. Artificially low interest rates and easy credit encourages investors to invest in things that people don’t actually want. When you produce things that people don’t want, you end up with a “general glut” (an excess of supply that you can’t sell). Enterprises can’t turn a profit and will either go under or lay off workers to cut costs. If governments and banks would just not try to stimulate the economy with easy credit, the business cycle wouldn’t be a problem.

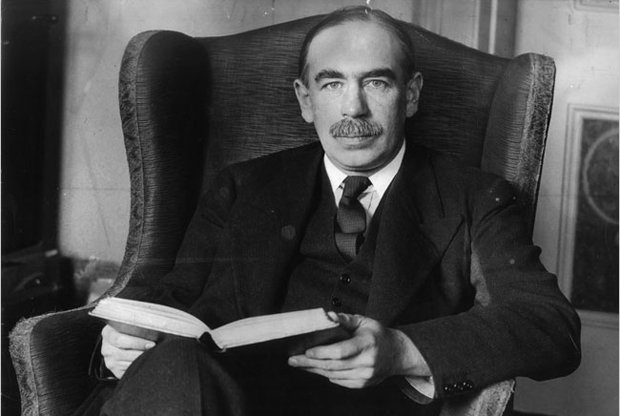

Keynes

John Maynard Keynes argued that once recessions set in, it can set off a “deflationary spiral.” The market won’t necessarily be self-correction, so it may require government intervention to fix things. When there is a recession, enterprises can’t sell all of their products because aggregate demand is too low. Consequently, enterprises can’t turn a profit. Due to the economic downturn, employers will start laying off workers. Since workers are also consumers, this will cause aggregate demand to fall even more, exacerbating the problem further. The economy keeps going deeper into depression until the government intervenes to fix the problem. For example, the government ended the Great Depression by boosting aggregate demand. The government increased spending in order to fund U.S. involvement in WWII (government spending increased aggregate demand) and it raised the top marginal tax bracket, which induced employers to raise wages (higher wages also boosted aggregate demand). You end a recession by having government intervene and artificially boost aggregate demand.

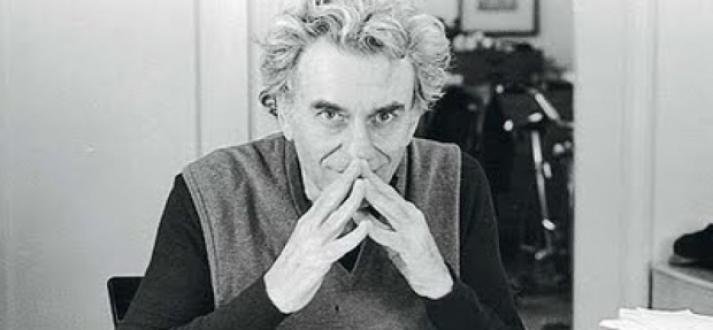

Minsky

Hyman Minsky argued that stability is destabilizing. When the economy does well for a long period of time, people have a tendency to become overly confident and start making riskier investments. Like Marx, he viewed the boom-and-bust cycle as being inherent to the capitalist system. He suggested that a job guarantee (government as an “employer of last resort”) could work as a countercyclical measure to prevent deflationary spirals and keep the business cycle from getting out of hand.

Friedman

Milton Friedman observed that the money supply contracts during recessions. Thus, monetary policy is a key factor. After the run on the banks that began the Great Depression, banks ended up going under. A large part of the money supply faded into non-existence. There was not enough money available for the economy to run properly. There were “too many hands chasing too few dollar bills.” There wasn’t enough money available for employers to afford to hire enough workers to maintain full-employment—the economy could not maintain full-employment because there was not enough money in existence. The solution is for the central bank to inflate the money supply. When there is not enough money available (and price levels in general start to go down), the central bank needs to make more money available. Thus, the treasury and central bank ought to aim for a moderate level of inflation in order to allow for economic growth. Don't let the money supply contract and recessions won't take place.

Kohr

Leopold Kohr proposed a size theory of the business cycle. He based his theory on the law of diminishing marginal productivity. When things become too large, they tend to become inefficient. If you own a field and are harvesting crops, hiring a few workers to help harvest will increase your productivity. As you hire more workers, at some point adding additional workers will not be worth it. Eventually, hiring more workers will actually diminish productivity. If you have too many workers harvesting the crop, then they will just be getting in each other’s way and holding up production. Everything has an optimal size. This holds true for every factory, industry, and economy. If anything expands past its optimal size, it will become unmanageable and inefficient. A recession is essentially a correction in which the invisible hand of the market is attempting to reel things back in and shrink enterprises and the economy back down to their optimal size. The way to avoid recessions, then, is to avoid letting enterprises or nations grow too large—stop expanding beyond optimal size.

Fisher

Irving Fisher had a debt-deflation theory of business cycles. During recessions, there is deflation (a contraction of the money supply and a corresponding increase in the value of money). During a recession, the level of debt in the private sector rises in real terms. The value of money increases, so the real value of debt increases. This causes people to default on their loans and mortgages. Defaults cause banks to become insolvent, so they reduce lending, which reduces spending (aggregate demand falls).

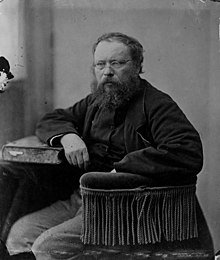

Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon argued that business cycles are largely the result of the institution of private property and the profit motive. Like Marx and Minsky, he thinks the problem is inherent within the system.

Employers attempt to maximize profits by keeping wages as low as possible, cutting costs, and increasing efficiency. The result is that productive capacity outstrips consumption. Additionally, workers are given wages that are too low to allow them as consumers to purchase the things they produce. The product is always sold for more than what the worker gets paid for producing it. In the aggregate, this means that workers collectively cannot purchase the whole of the supply of products they create. Thus, there will be an excess of supply (general glut). Enterprises will have to lower prices in order to clear markets—their merchandise becomes cheap (deflation). This results in lower profits, which causes creditors and lenders to withdraw funds and stop investing in such enterprises.

Furthermore, the insititution of property allows banks to steal property through foreclosure. Suppose that I get a mortgage for $30k in order to acquire land, then I build a $60k home on the lot, and over the course of a decade or so pay $20k towards the mortgage. For some reason, I end up getting injured or losing my job and can't keep up with payments. I end up defaulting and the bank forecloses on the property. Now, for a $30k debt, the bank has taken the $30k lot, the $60k home that I built, and kept the $20k that I already paid—they have legally stolen $80k worth of value from me. (I intentionally left interest out of consideration for simplicity's sake.) This is why Proudhon famously said, "Property is theft!"

It should be noted that capitalistic property arrangements not only involve implicit theft but also incentivize banks to make bad loans. There are profits to be made on foreclosures under capitalism. Consequently, it is not necessarily in the interest of the bankers to ensure that they only give loans to people who will be capable of keeping up with the payments. The banks might actually find it in their interest to make loans to people who will not be able to keep up with their payments. Provided that the mortgagor is able to keep up with the payments for a while, the mortgagee (bank) will be able to make a profit off of foreclosing on the house and selling it again. If bankers make too many such unsound loans and too many people get foreclosed upon, it can spark an economic downturn that ripples throughout the whole economy. If I lose my house to foreclosure, I’m going to be in bad shape and won’t be able to spend as much on luxury items. If too many people find themselves in this situation, it could lead to a fall in aggregate demand.

Conclusion

I beleive that all of these insights are valid. The reality is that there are multiple factors that lead to recessions. A comprehensive general theory of the business cycle would need to take all of this into account and more.

And if we kept doing the work to keep us supplied, while refusing to account for our consumption through money and debt?