The official interpretation of history in the Soviet Union

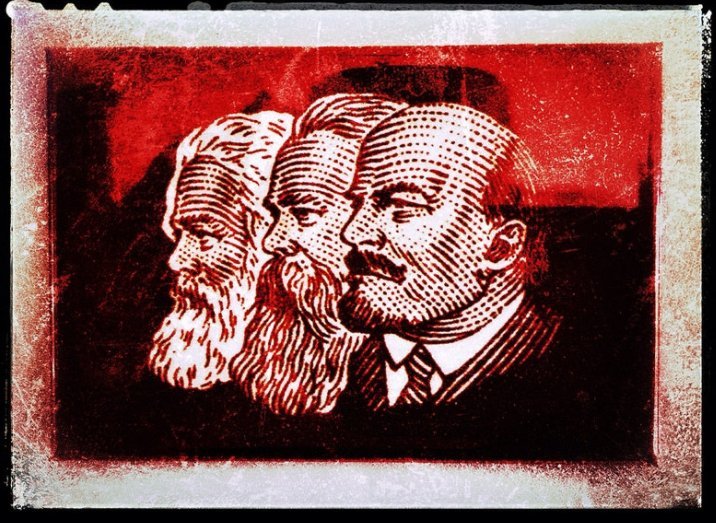

History in the Soviet Union was regulated by the official ideology, marxism-leninism, and supervised by the Communist Party. The official understanding of history was deterministic: history was governed by objective laws inevitably leading humanity from primitive societies through slave societies, feudalism, capitalism, socialism and finally to communism. By an additional doctrine to classical Marxism, introduced by Lenin, the Communist party of the Soviet Union obtained status of an political “avant-garde”, a group assumed to have obtained profound insight in the laws regulating history. The interpretation of history formulated by the Party was mandatory and prescriptive. Soviet historians, specialists within other disciplines, as well as writers, artists and journalists, should not present the past and present as it was, but in its development towards socialism and communism. Guided by the insights and wisdom of the Communist Party historians would obtain a “scientific” knowledge of the laws driving history and society. Dissenting views were punished.

Communism, the end goal of history in the Marxist doctrine, would be a classless society and all contradictions, including between nations, would be dissolved. As regards the latter, they would start to gradually disappear already under capitalism, as the capitalist economy demanded growing internationalization and maintaining national borders would impede development. Contradictions between nations would be further weakened under socialism. In the Marxist view nationalism originated from the idea of the nation-state and the need to control a territory, within which a capitalist marked could be established. Thus nationalism was a tool in the hands of the ruling classes. Socialism would not only abolish capitalism and the class society but also make redundant the nation-state.

Indegenization vs Russification

However, even if Lenin and the Russian Bolsheviks regarded nationalism as a phenomenon of the past, on historical decline and contradicting the “internationalist” principles of marxism, they understood that a revolution and overturn of the Russian czardom could not be accomplished without support from the non-Russian nations and national minorities in the Empire. Out of pragmatic considerations they supported demands of self-determination and even independence for some of the non-Russian nations. However, once the Soviet power was established, claims of self-determination were transformed from a factor objectively supporting revolution to a factor threatening its achievements. Stalin announced that the principle of self-determination should be confined to the workers and be denied the bourgeoisie. The Red Army was deployed to subvert attempts at independence in the non-Russian part of the former Empire.

Lenin tried to win the minds and hearts of the non-Russian peoples by repudiating the late 19th century’s Russification policy and initiating a policy aimed at strengthening the culture and languages of the national minorities and at creating new elites among them that would support the Soviet regime (the so called ‘korenizatija’, (indigenization) policy). By the end of the 1920 Stalin reversed this policy which, as it turned out, had created elites that were more inclined to cultivate national rather than “internationalist” Soviet ideals. The ‘indigenization’ policy was replaced by an assimilation policy closely resembling the late 19th century Russification policy.

Rewriting of history: Back to Empire

While in the first years following the Russian revolution the Bolsheviks had interpreted movements for national independence and resistance against imperial Russian domination as historically progressive, now different interpretations of history were required, ordered by Stalin. The role of national movements in the historical progress towards revolution and socialism was downplayed to the favour of Russian czars, princes and colonizers that had gathered the Russian lands, furthered the emergence of a strong, centralizing power and defended the Russian Empire against foreign intruders. The Russian Empire had, in the new interpretation of Soviet historians, not suppressed but on the contrary saved many nations from a destiny far worse than coming under Russian domination.

History books dealing with non-Russian peoples national past had to adjust the description of actors and events to the historic trajectory of Russia. Stalin openly paralleled himself with Russian czars and other prominent leaders in Russian history. In literature and films Russian empire-builders and pre-revlutionary defenders of Russia's interests, such as Peter the Great, Ivan Groznyj, Dimitrij Donskoj (who defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380), Alexander Nevsky (who defeated a Swedish army at Neva in 1240) were glorified. Russian literary classics became ideal models for the Soviet literature. Ranking order of the czarist army was reintroduced in the Soviet Army. The Russian Ortodox Church was legalized and when Stalin in 1945 proposed a toast to the victory over Germany in 1945 he thanked the Russian, not the Soviet, people. The new Soviet anthem, replacing the “International” confirmed Russia as the leading nation. It started with the sentence: “The Union of invincible, free republics has been strengthened for ever by the Great Russia”.

New rewriting of history, back to "indegenization", political liberalization

In the 1950s Nikita Khrushchev modified Stalin’s Russification policy and a rehabilitation of the histories of non-Russian peoples was initiated. Soviet historians were once again asked to rewrite history. Leaders of national liberation movements again surfaced in history books. Stalin’s brutal suppression of non-Russian nations, including the purge of their national elites and the deportations of entire nations to Central Asia and Siberia at the end of World War 2 became themes at least partially possible to discuss. The cultivation of non-Russian national particularities and traditions became legitimate. Lenin’s “indigenization’ policy was revived- with the same unintended effects as in the 1920’s: elites in the non-Russian republics took advantage of the possibilities offered by the new political orientation of the party leadership.

This time the effects had lasting results. Khrushchev liberalization paved the way for processes that 30 years later contributed to the final dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Awesome post girly, thank you for the breakdown. An interesting read to say the very least.

You are welcome. Thanks for commenting and reading.