My parents didn’t teach me Spanish, I have an Alabama accent, and I have no memories of Mexico. Still, the president thinks it’s a good idea to deport me.

By CESAR VIRTO September 06, 2017

Facebook Twitter Google + Email Comment Print

My parents brought me to the United States when I was 3 years old. I’ve gone to school here, worked here, paid taxes. I’m as American as you are.

On Sunday, I learned that the president wants to send me back to Mexico. Or, at least, he isn’t willing to defend my right to stay here. Either way, my life is about to be radically upended.

Story Continued Below

My parents didn’t teach me Spanish. I grew up in a small town in Alabama, speak with a Southern accent, and didn’t even know I was undocumented until I was 16 years old. I grew up reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, and have always considered this country my home.

Now President Donald Trump plans to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, and I could be deported to Mexico, a country that is completely foreign to me. I’d have nowhere to live, no family to stay with and no way to find work. I would live in a different country than my American wife, who without financial support would have to sell our new house.

A rally defending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program is pictured here. | Getty Images

LAW AND ORDER

The Legal Flaw With Ditching DACA

By DANIEL HEMEL

My story isn’t an unusual one. Like countless others, when I was an infant my family fled from poverty and cartel violence. After they crossed the border, they settled in a small town in northwestern Alabama. My parents made sure I learned English, and as a child when people asked me where I was from, I told them Alabama without hesitation. To me, that was the truth.

I first heard the word “undocumented” when I was 16. I enrolled in driving classes at my school, but I was told I couldn’t get a driver's license because I didn’t have the right documents. Until that point, I had no idea I was considered an “undocumented” person in America. It crushed me to find out. For years, I was angry at my father for not coming into the country the “right way.” Looking back, I suppose my parents were afraid to tell me the truth, or didn’t want me to be afraid.

Once I realized what being undocumented meant for my life, things got hard. My family couldn’t afford to send me to college, and since I wasn’t an American citizen I couldn’t qualify for college scholarships or financial aid. I was tempted to quit school because there didn’t seem like much of a point. After graduation, my classmates talked about their future, and when they asked me what my plans were I would say nothing because I was too embarrassed to tell them I was undocumented.

Because it is difficult to find work without papers, friends and family encouraged me to get a fake ID and take a job in an immigrant-heavy industry like construction. They told me it was the only option. But I felt that relying on a fake ID was wrong, and I was determined to obtain an education and job legally.

Luckily, a white couple from a few doors down began helping me. They introduced me to their church, which I started attending. I worked odd jobs during the day, and at night researched colleges that accept undocumented immigrants. When I expressed my interest in attending a Bible college, members of the church helped me pay the tuition. I started attending the college that fall.

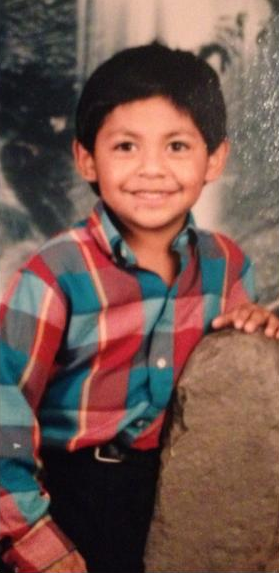

Cesar as a child in Alabama.

Cesar as a child in Alabama. | Courtesy of Cesar Virto

When President Barack Obama implemented the DACA policy a few years later, everything became easier. I immediately applied for a driver’s license, Social Security number and work permit. I remember taking my first road trip with my valid driver’s license. I went to the beach to visit a friend, and for six hours I cried like a baby because for the first time in my life I wasn’t scared of getting pulled over by the police. Each mile I drove felt like a pound no longer weighing me down.

A few months later, I graduated from an accredited institution, the first in my family to do so. I found a job with a Christian book company in Nashville, Tennessee, with full benefits. Like many others, I was the first DACA employee my company had hired. A year later, I got married and bought my first home. Because of DACA, I finally felt like I was achieving the American dream.

My wife and I consulted with lawyers on how I could achieve legal residency, but they all said I would have to first leave the country, and that it isn’t guaranteed the government would let me back in. That’s a risk I can’t take. If I can’t return to my job in Tennessee, we will probably lose our house. My wife would have to drop out of college because I pay the tuition.

Cesar on graduation day.

Cesar on graduation day. | Courtesy of Cesar Virto

When Trump announced the end of DACA, my old fears returned. I thought I would never feel that kind of anxiety and dread again, but I was wrong.

Once DACA ends, I will no longer have the work permit I need for my job. I am also an Uber and Lyft driver, but without a valid driver's license, that source of income will disappear, too. If we lost our house, we have no family in Nashville to stay with. I’ve been working toward my master's degree, but that would have to be put on hold, too.

Even scarier is the prospect of deportation.

I haven’t been to Mexico since I left as a 3-year-old, more than 25 years ago. I have no memory of the place, and I’m culturally American—I would feel more like an outsider there than I do here. I have no clue how I would make a living, or where I would go. I had the opportunity to take some Spanish classes in college, but I speak it with an Alabama accent and can’t read or write the language well. I feel trapped—Hispanics make fun of my pronunciation and tell me I act like an American, and Americans say I do not look like them and need to go back to where I came from. I do not know how to act any other way. I am me. It hurts to be told I do not belong wherever I go.

But what hurts me the most—more than the alienation, more than the fear—is the sense of betrayal. It pains me that many of the same Christians who supported me as a youth, who helped pay my college tuition, can turn around and chant, “Build the wall.” People I love post things on Facebook that break my heart. If I were any less grounded in my faith, I honestly would have left the religion.

But I’m glad I didn’t leave, and as a Christian, I am trying to understand the points of view of those Christians who would like to see me deported. Many of them, I know, are struggling in their own lives. I pray that our shared faith will give them compassion for immigrants like me, and I wish that we can love one another as much as I love this country.

I'm also praying for a solution. I hope that Congress will put in place a path for me to keep the life I’ve worked hard for, but my wife and I are preparing for the worst. My priority is providing for her, but there are no guarantees.

In the meantime, I take refuge in my faith. “But our citizenship is in heaven,” says Philippians 3:20. “And we eagerly await a Savior from there, the Lord Jesus Christ.”

Its really sad to hear about you. Do not lose hope and keep fighting nobody has a right to deport you. He himself is not native American so how he can justify his policies.