The destructive practice of conventional mining is what terrifies common people most when it comes to the alleged extractive activities at the ocean bottom. Indeed, the centuries-old history of various types of onshore mining can represent thousands of dreadful examples when beautiful landscapes were irrecoverably destroyed in favor of the fossil fuels and minerals enabling another industrial revolution to move on.

The disastrous results of the conventional extractive industry may vary significantly in their dynamics. They include both direct and indirect negative consequences the people and nature have to face. They can have both explosive and durable impacts. The giant holes in the Earth left after multi-year open-pit mining are visible even from space. Explosions on oil rigs take lives away from people within hours.

It’s weird but the extent of technological development does not correlate with the environmental security. The more people develop their technologies the more biosphere suffers from the adverse effects of human activities.

That’s why the whole discourse of the present ecology activists is grounded on the presumption that any new mining technology will affect the natural environment no matter how eco-friendly the technology is designed. The common ignorance plays a role in such situation as usual.

Besides, the populist practice of overloading social networks with strong rhetoric against open-pit mining, for example, resonates well with the fancy anti-globalist and anti-capitalist proclamations of the contemporary post-industrial movements in the economy.

It would be interesting to know whether those activists are ready to give up their smartphones, computers, electric vehicles, advanced medical equipment in the hospitals, solar panels as well as many other consumables created with the technological achievements of the 21st century. Can they really refuse their national military forces that are powerless without the advanced weapons and ammunition?

The thing is that just the minerals such as nickel, zinc, cobalt, copper, and manganese provide the very existence of all those technologies that allow the activists to share their angry anti-mining thoughts on socials.

The massive return of such activists to the pre-industrial era is hardly imaginable, to say the truth. We will come back to this issue a little bit later, however.

The environment protection discourse is quite clear in case of the conventional onshore mining since the industry is mature enough to be legally regulated whatever jurisdiction any mining area belongs to. If desired, Greenpeace together with the other environmental activists can find out the exact legal measures how to press both the national and transnational mining corporations with regard to one or another ecological concern.

In many cases, there is no need to reinvent the wheel since the absolutely apparent effect of mining is available. Take the Philippines, for example, where the governmental ban on the open-pit mining of nickel ore is self-evident from the ecological perspective.

On the one hand, the drinking water shortage inherent in any island country makes artesian wells confront the huge open-pit mines in the Philippines. Even though the national Philippine economy suffers from a decline in nickel ore production, the very survival of the 100-million population of the Philippines is at stake due to freshwater shortages.

Indeed, in the choice between wealth and health, the latter is always more desirable.

On the other hand, thousands of hectares of the Philippine landscapes are irreversibly destroyed by the open-pit mines. Everyone, hand on heart, should admit that open-pit mining is sacrilege even for the huge lands such as Siberia, and it is nothing but the true vandalism in case of island states where the land scarcity is obvious.

Nevertheless, it is not hard to imagine that the ban decision was made by the Philippine government through quite a durable struggle between the actual economic benefits from nickel ore mining and the ecological arguments. President Duterte cannot fail to understand that losing the multi-year leadership in nickel ore production the Philippines can lose something more valuable than just a part of the income to the State budget. It comes to the international prestige of the Philippines after all.

Times change, and most probably the Philippine leaders have another vision how to diversify the national economy to become less dependant on nickel ore. We are going neither to read the tea leaves nor to advise the Philippine government. However, there is yet another solution allowing to hold the nickel leadership while the open-pit mines are closed totally over the whole territory of the Philippines.

How to arrange the issue making “the wolves sated and the sheep intact”, as people say?

First of all, it is necessary to address the issue from another angle by breaking the mental link between mineral mining and onshore lands. Even though the Philippine territory is relatively large, the island state should be considered as a ship which courses through the ocean (two oceans — Pacific and Indian to be precise in case of the Philippines).

Why? Because the ship’s crew has to obtain everything they need from the sea. This is a different behavioral pattern inherent in fishers and pirates, for example. Leave aside negative connotations with pirates — they never plunder their own ship…

Both fish and merchant vessels constitute clearly recognizable objectives for either fishers or pirates. How can mineral resources belong to the modus operandi implying exploitation of the sea?

Here we cannot avoid a brief historical overview.

Seabed minerals in the form of polymetallic nodules and crusts were discovered first more than 150 years ago. The practical stage of the seabed minerals’ exploration, however, peaked in the 1960–80s. That was a period when submarine technologies flourished due to the Cold War confrontation where military submarines played a significant role. Besides, the onshore mineral deposits have been already distributed overwhelmingly among major national and transnational mining entities at that time. The ocean bottom beyond the 200-miles exclusive economic zones was remaining the “aqua incognita” capable of bringing the new discoveries in the field of mineral treasures.

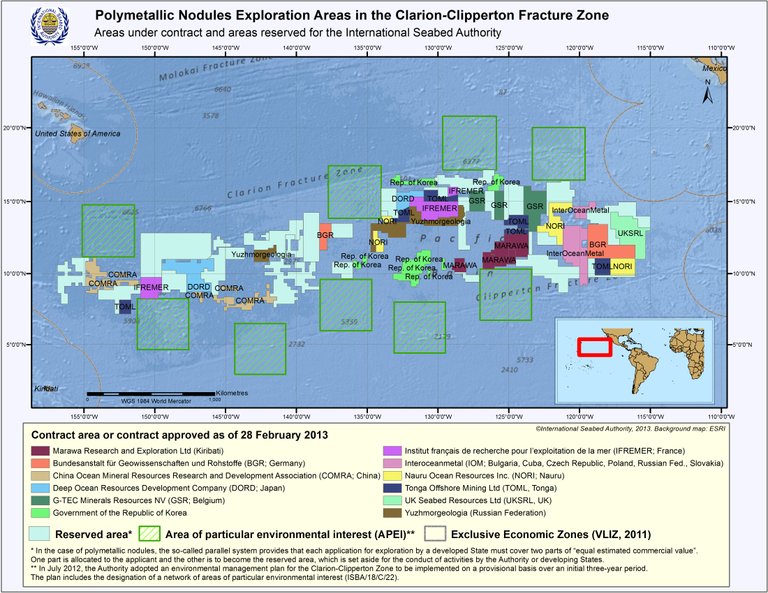

About 20 countries participated in the deep sea explorations one way or another under control of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) — the specific UN body aimed at regulating the ocean floor exploitation. Just at that period, the biggest and richest seabed mineral deposit of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) was explored in general to realize what enormous mineral treasures were sleeping there. That was the euphoric time of the seemingly approaching “New Gold Rush”.

The CCZ lies between Hawaii and Mexico in the Pacific ocean formally belonging to nobody. That’s why the ISA issued special licenses to those countries whose scientific organizations (no matter state-owned or private) were able to undertake research activities in the Zone. Thus, the CCZ is divided into several areas where the official contractors have rights to explore and mine seabed minerals.

What mineral treasures are involved?

Professional miners should now sit down and hold on their chairs.

According to the most conservative estimate, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone contains 62 billion tonnes of polymetallic manganese nodules, sufficient to extract 17,500 million tonnes of manganese, 761 million tonnes of nickel, 669 million tonnes of copper and 134 million tonnes of cobalt. Since the average market price of metals containing in a single ton of nodules is about USD 1000, the entire deposit can cost about USD 62 trillion! Triple than the US national debt, by the way…

Flash forward: nobody conducts commercial mining in the CCZ up to now — those trillions are still waiting for their treasure hunters.

In the 1990s the political situation in the world radically changed due to the collapse of the communist bloc. The multi-year economic stagnation of the former USSR countries such as Russia and Ukraine affected their deep sea exploration activities. On the other hand, the corporations from the “capitalist bloc” reached the mineral deposits in those terrains where they were prohibited to enter during the Cold War. It so happened that the oceanic “New Gold Rush” was de-emphasized once the high finance opened the post-Soviet developing world up where poorly democratic but highly corrupted governments easily provided the transnational mining corporations with concessions on mineral mining.

To tell the truth, the global political transformation was not the only reason for suspending the commercial seabed mining. There is another purely technical reason — the pressure.

The thing is that the richest seabed mineral deposits reside at a depth of 4–6 thousand meters. The tremendous pressure of 400–600 atm significantly limits the range of equipment capable of working at such a depth. From a technological perspective, it is much easier to launch a rocket to space with a zero pressure that to create a seabed harvester capable of collecting minerals from the ocean bottom.

By the way, isn’t that a pragmatic background of the commercial success of such fancy projects as SpaceX and Virgin Galactic? It would be interesting to know whether Elon Musk, for example, failed to face up to the “pressure challenge” of deep sea exploration in favor of space flights while the hypothetical profit from seabed mining was many times greater than everything SpaceX could find on Mars?…

Meanwhile, times keep changing. Today the onshore mineral deposits throughout the world are redistributed finally between all concerned parties. Only two large land areas remain terra incognita from the mining perspective — Antarctica and North-East Siberia. And most probably they both will remain in the same state indefinitely: Russia covers Siberia like a slumbering bear, Antarctica is closed for mass exploration at the international level after 1946 when the expedition of American admiral Byrd was attacked near Dronning Maud Land by either UFOs or escaped Nazis…

Another impulse of the present times implies two parallel trends: phasing out fossil fuels and strengthening public awareness regarding environmental protection. Both trends confront the conventional mining directly and indirectly.

While the global shift to alternative energy sources is removing the obsolete oil-driven economy, the demand for such battery-related minerals as copper, cobalt, and nickel keeps growing. The contradiction requires being resolved with some non-trivial solutions since just brutal enlargement of the open-pit mines, for example, is hardly possible in these days of strong environmental responsibility. The above-mentioned case of the Philippine ban is a living illustration of this. The issue is becoming so burning that some hotheads seriously suggest to consider even asteroid mining…

Thus, the common logic brings us back to the seabed mining urgency. It seems everything checks out here since the ocean bottom can provide the humanity with minerals for hundreds of years while the lands will remain intact in the sense of new mines, especially when the proposed State-as-a-ship policy is accepted.

And yet we approach the same problem as conventional mining faces today — what is the extractive technology which can provide the eco-friendly commercial seabed mining?

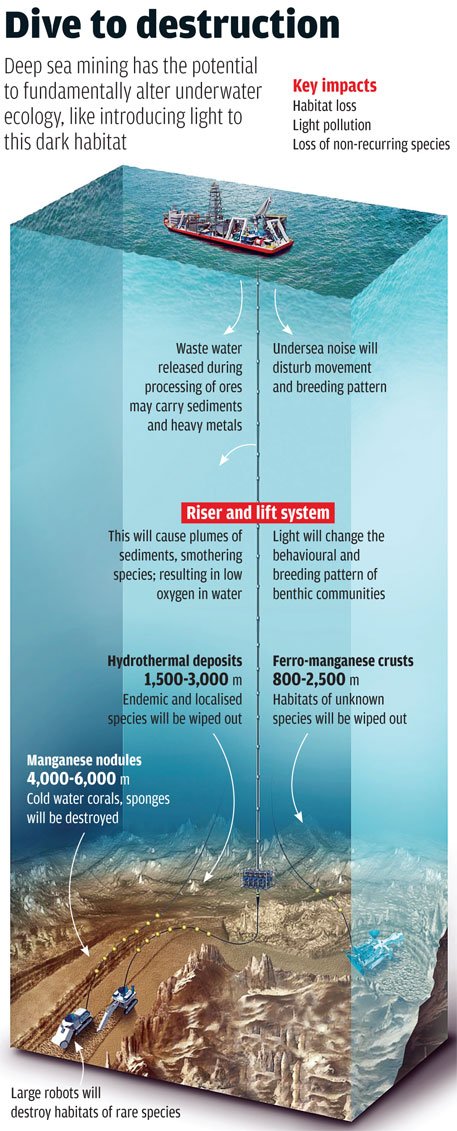

It doesn’t take a great deal of wisdom to realize that drilling and excavation can hardly meet the mining methods acceptable for the ocean bottom. The submersible bulldozers created by some famous mining contractors are still staying ashore once both technologic and ecologic capabilities of such equipment are highly questionable. Taking the path of least resistance, the creators of those deepwater bulldozers were counting probably on the usual ignorance of the world community who would turn a blind eye to how miners transform the ocean bottom into a lifeless deepwater desert. In addition, nothing revolutionary new was necessary to adapt conventional excavators for the remote deepwater operation.

But the reality proved that they were mistaken with both assumptions.

On the one hand, the recent noise around plastic contamination of the oceans (by the way, where were all those activists when the present 3-times-of-France-size garbage patch was “only” one-France-size?) is adding fuel to fire of the worldwide ecology awareness — Greenpeace will eat up everyone who dares to damage oceanic biodiversity.

On the other hand, the excavators crawling over the oceanic floor will have to transfer the collected minerals to the surface somehow. And the proposed pipe-and-pump systems appeared technologically inappropriate for operating at the depth of 4–6 km.

Even if a piping system capable of connecting the bottom machinery with the vessels at the surface can be created, another more serious problem will remain: the process implies a huge amount of sludge along with highly mineralized bottom water to be pumped back to the ocean after extraction of nodules. It implies the second piping system working in the opposite direction. It is worth understanding that the sludge with bottom water cannot be just drained overboard because such a mud mass will be settling down for decades. It can contaminate the ocean through the entire water massif from the surface to the bottom. Besides, the settling sludge will cover the other areas of the ocean floor burying the nodules.

The peculiar feature of the oceanic mineral deposits which distinguishes the seabed mining from the conventional onshore one is that polymetallic nodules are generated over the vast bottom fields. And it happens all the time. The thing is that the “mining” term itself is less appropriate for the deepwater extractive process than, for example, “collecting” or even “picking up”.

That’s why a different technology is to be applied to the seabed mineral “harvesters” — they should levitate over the ocean floor due to positive buoyancy in order to freely move along broad seabed areas where nodules are distributed.

Hence, the combination of the following three major drivers can lead to a practical implementation of the next evolutionary stage of mining or the Extractive Industry 2.0, as we call it:

the global paradigm shift from the present oil-driven economy to the one based on energy accumulation technologies where such minerals as zinc, cobalt, and nickel play a crucial role (the contemporary analysts warn about cobalt price keeps growing);

the new “pirate” behavioral pattern making governments perceive their states-as-a-ships when mineral resources for the local economies should be obtained from the outside oceans if possible. Even though nothing prevents every country to follow such a practice, it especially concerns the island states where land shortage is actual;

the progressive eco-friendly technology of the deep sea mining which is based on the autonomous submersible vehicles capable of collecting seabed minerals as carefully as you pick up mushrooms in a forest glade.

When the first two drivers belong mostly to the socio-economic realm, the third one relates to the scientific and technology vision. At first sight, just the seabed mining technology is the weakest link in our chain of reasonings. And it would be so if we hadn’t the actually running project meeting every requirement of the advanced seabed mining.

That’s why we dare to hope for coming changes in mental patterns of the island state leaders that can result in establishing the environmental savvy economies with a growing market of seabed minerals.

Moreover, the issue is urgent due not only to the purely commercial concerns. The very nature of polymetallic nodules’ generation implies a non-stop process happening at the ocean bottom all the time.

In other words, the ocean is a huge natural factory which produces mineral deposits 24/7. And in contrast to onshore minerals, the oceanic deposits are renewable!

Even if the whole humanity starts mining seabed minerals today, the oceans will reproduce their mineral treasures much faster than people can extract them. To put it in economic terms, supply will always exceed demand.

In light of such a situation, the Philippine ban looks like a progressive approach to the future of the extractive industry as if the state leaders seemingly aimed to benefit from the never-ending seabed deposits.

Another island state Indonesia should pattern itself on its traditional competitor in mineral mining — the seabed areas around both countries are full of polymetallic treasures.

So, the only thing necessary to start the actual seabed mining is the true statesmanship.

Where will the countries get the expertise and technology? — we will provide them with both.

P.S. We will continue exploring the seabed mining opportunities for various areas — India, Japan, China, The Middle East, Mexico… almost every country on the Globe can be involved one way or another into what we call Extractive Industry 2.0 to benefit a lot from the true God’s gift — the Earth oceans.