(JP/ PJ Leo)

I was three months shy of turning 8 years old on Aug. 17, 1948, the country’s third Independence Day, and preparing to go to Bireuen in Aceh, the “city of struggle” — so named because it had been the center of the revolution for independence from Dutch and Japanese colonization.

My father called me to proudly show a stack of papers, surat obligasi (state bond certificates). He asked me to read each word and beamed with pride as I could read very fast, he himself being almost illiterate with only a second-grade formal education that had been forced by the Dutch. The Acehnese considered going to Dutch “infidel schools” as haram.

My father kept buying such certificates even after the two DC 3 planes Sukarno had asked the Acehnese to finance in order to establish national flag carrier Garuda Indonesian had been bought, not only with the money from those certificates, but also from jewelry given by Acehnese women.

My father continued to buy them like many other prominent Acehnese in those days, as a symbol of his love for the Republic, until one day in the early 1950s, when the post office that sold them said the papers were worthless.

I don’t know what exactly triggered the recent excitement over these obligasipapers, except for President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s encounter with one living donator.

“My grandfather sold 50 cows to buy these certificates,” a man told a local newspaper.

The 90-year-old was dragged to Jakarta for a televised interview, flying for the first time in his life on a Garuda flight that in theory he partly owns.

And as usual in Aceh, there are heated coffee shop debates on the issue. One man said: “If I were Jokowi, I will buy back all those certificates and tell the Acehnese to shut up,” to which another responded, “Indonesia will go bankrupt if it had to pay back all its debts to Aceh.”

Another one countered: “Don’t be stupid, Jakarta will pay with our own money, as usual,” explaining how the central government continued to rob Aceh of its natural resources.

Several Acehnese politicians have also taken up the issue. This sudden controversy over the bond certificates seems a mere symptom of continuing deep-rooted bad feelings against the central government. The situation in Aceh today could probably be described as a mini Charles Dickens setting: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

Big and modern malls are opening in several cities, their well-paved roads clogging up with new cars and new cafes opening up every week all over the place.

Indeed, the image of being rich is such that even the police at the border with North Sumatra regularly stop cars bearing BL plates (Aceh registration number) to extort bribes with made-up offences, so blatantly that even the Aceh provincial police chief once aired his protest to his counterpart in Medan.

Yet Aceh remains among Indonesia’s poorest provinces, second-lowest in educational achievement, and unemployment is much higher than the national average. There is a general feeling of helplessness, of frustration and humiliation for being treated condescendingly. The economy is almost totally dependent on government spending. Even eggs are still imported from its traditional rival province of North Sumatra.

Regulations are introduced to strengthen the stranglehold over Aceh, which is officially a “special status province”. Seven decades after independence, the Acehnese still have to suffer power blackouts almost daily, while the electricity the province produces is prioritized to supply neighboring Medan, an industrialized city compared to “agricultural” Aceh.

It is the anger at having to wake up at 3 a.m. daily to turn on their water pump machines to get clean water from the state water supply system or drink unclean water from wells. It is the humiliation of having to put up with questions from the police and military intelligence for hosting cultural and educational conferences with foreign delegations, despite them having proper visas. Aceh is still considered a conflict area on par with Papua, almost 13 years after signing the peace accord and being touted as one of the world’s most successful post-conflict peace management models.

Aceh is still boiling under the surface of peace and tranquility, like the proverbial api dalam sekam (fire in husks), just waiting to suddenly explode out of control. The signs are everywhere: ex-combatants are rebelling openly against former commanders who are getting super rich while former soldiers linger on in abject poverty; ordinary people are seeing electoral campaign pledges as merely cat langet (painting the sky); job seekers are told openly to provide letters of rekomendasi from well-known officials, or not bother applying at all.

To top the insult, Garuda Indonesia’s inflight magazine explained a few years ago the name of its first planes, Selawah 01 and Selawah 02, as to mean “gold mountain”, without even mentioning where that mountain is supposed to be, let alone the true story behind the name.

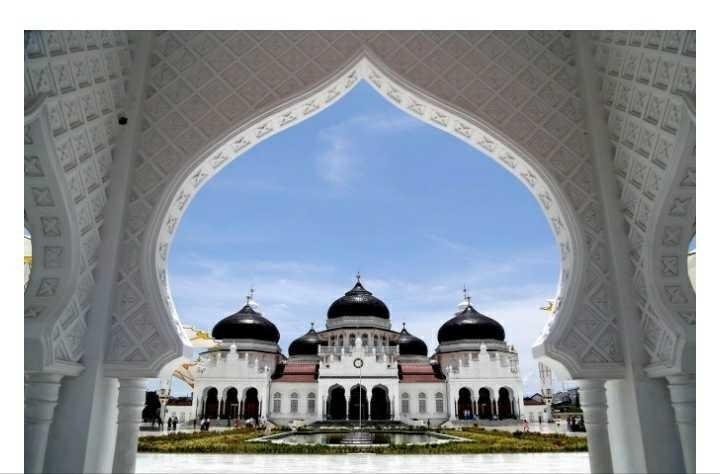

Actually, Seulawah Agam and Seulawah Inong (male and female Seulawah) are the iconic twin volcanic peaks towering over the capital, Banda Aceh. The “male” volcano is still active, with its conic peak being sung as “touching the sky” in Acehnese folklore, and the “female” as having “children”, the cascading hills on its side formed by lava after erupting hundreds of years ago. Under the hills, things are far from peaceful as long as several issues — including Aceh’s “autonomy” and the lack of it, along with persistent inequality — remain unaddressed. Nur djuli

When using #whalepower Tag , Same Post Content , All Flag. https://steemit.com/artzone/@rouzatuljannah/mosque-aceh-lost-jakarta-ca50b48d0c691

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2018/04/23/i-want-my-money-back-lost-love-of-aceh-jakarta.html

Very interesting, I have always been interested in Indonesia's culture but know very little about what life is like in Indonesia today.