This is a continuation of the series, Morality in the Modern World, (start from the beginning here). If you missed the last one, Manners in the Modern World, click here. The goal of this series is to promote a secular theory of ethics that all people can follow. Religion, though not without cons, was once a potent force in guiding its followers to good will. With religion deteriorating in the modern world, a void in moral theory has been created, and has allowed for some truly dumb ideas to gain traction. I aim to fill that void with a consistent, practical theory of what constitutes good and bad behavior.

The title of this post is rather vague, and doesn’t sum up my real mission here. So here’s the problem: Imagine you’re taking a walk beside a pond when you spot a young boy splashing in the pond, struggling to stay above water; he starts to drown. What do you do? The reader might jump here and think “well jump in and save the poor kid!” But let’s say you’re not a good swimmer? What if rescuing him would bring substantial risk to yourself? The question specifically is, in order for morality to be practical, how much should each person be required to give up for the good of the whole? My goal here is to deduce a general rule that will allow us to properly gauge, for lack of better phrasing, how much of your stuff belongs to me, and if this question even makes sense.

As we venture for an answer, we will find that this is one of the hardest questions in ethical philosophy. But, I think we will find an acceptable answer here, as we can to all questions.

The Golden Rule

Jesus said, “do unto others, as you would have them do unto you,” and at first glance we may think, well, there you have it; our general rule. But upon further inspection, this is a very arbitrary rule. There is practically no limit to the benefits we’d be willing to accept from others, at whatever cost to them. You could write this out in a slightly more reasonable way, for instance, “do not ask or expect others to do for you more than you would be willing to do for them, or accept from others only as much help as you’d be willing to extend to them if you were in their position.” This is a much better rule, but it’s still too arbitrary, as the opinions of individuals are bound to vary widely.

And this is another problem of ethics for which I have discussed at some depth, but it still needs further attention: people have different opinions on even the simplest of things. There may be some people who believe it immoral to give up anything for their fellow man, and we can find those on the opposite end who would be willing to give up everything for no one. Both worlds would be equally absurd. In the former, we live in a world where no one is brave enough to be a police officer, to fight fires, to go to battle, to invest in business, to do anything outside of their own immediate personal gain. And in the latter world, would exist a society of such unselfish proportions that no one would be prepared to accept and benefit from the sacrifices of others.

We can reject both of those extremes outright, but this still leaves us clamoring to find what the general rule should be.

A Simple Answer to a Very Hard Question

Here’s what Henry Hazlitt, in his Foundations of Morality, thought the rule should be:

“Self-sacrifice is only required or justified where it is necessary in order to secure for another or others a greater good than that sacrificed.”

We could be more specific here, as it is impossible to measure exactly what constitutes a good in the universe. We can at least say that the goal of moral rules is to create the greatest social cooperation, and therefore, create the greatest possible number of interests for the greatest possible number of people.

Already this is much better rule than our previous Golden Rule. We’re borrowing some concepts from economics here, cost/benefit analysis and profit— because remember how closely related economics is to ethics. Before we decide to sacrifice our own good, we should ask “is this risk, or this thing I wish to give up, going to confer a greater good on others?” It could be reasonably argued that it would be immoral to sacrifice your own good to confer a lesser good on others, for this would reduce the total amount of good in the universe. So we should always attempt to create a good profit in the universe, using the best possible measurements of good. (See first post in this series for more clarification). Profit, in this sense, being the difference between the higher value of good obtained and the lower value of the good sacrificed for its obtainment. In other words, if I sacrifice my time, effort, and wealth to advance the beliefs of Nazism, I have undoubtedly created a net loss in the overall good in the universe. I ask the reader who disagrees here to kindly redirect their refutations to my own ass.

"What leads to the confusion is the difficulty, if not the impossibility, of conceiving of a society in which happiness and well-being were maximized but in which nobody ever sacrificed his short-run interests to the long-run interests of others, in which nobody ever did his duty, and in which nobody had any virtues. But the reason for the difficulty or impossibility of conceiving such a society is that is involves a self-contradiction in concept and in terms. For the same reason it would be an impossibility to conceive of an economic community in which the production of ultimate consumer goods and services was maximized without the use of labor, raw materials, factories, machines, or means of transport. What we mean by rational Self-Sacrifice and Duty and Virtue is performing acts that tend to promote the maximum of happiness and well-being for the whole community and refraining from acts that tend to reduce such happiness and well-being. If the effect of Self-Sacrifice were to reduce the sum of happiness and well-being it would not be rational to admire it, and if the effect of other alleged duties and virtues were to reduce the sum of human happiness and well-being, we would cease to call them duties and virtues."

— Henry Hazlitt, Foundations of Morality, pg 150

This is probably as simplified as we can make a problem with so many variables. And although I wish we could end it here and call it a day, there are still many implications that can be drawn that deserve further explanation. It could be argued here, that this is justification for forcing the rich to give up most of their wealth to the masses. Would they not be promoting a greater good, like the fire fighters or the soldiers?

No, for the same reason that the reader, who I’ll assume to be of average financial standing, is not forced to give up most of their belongings to the people of Bangladesh, who are actually just as comparably poor as the average man is to the very rich.

Such equal distribution of income, housing, clothing, food, quantitatively and qualitatively, would be physically impossible. Even if such a society were done completely voluntarily, the incentives to work and produce would be lowered so low on both ends to lead to universal impoverishment. “What a bold claim!” the reader may exclaim, but the reader should then be directed to the 100 million people who have died at the hands of communism in the last century. And I would argue that a large percentage of human suffering in the world currently, can still be traced to communism, simply disguised under different names. Forcing those with the most to give to the least in the aims of creating the maximum amount of good in the world tends to create the opposite, tends to destroy social cooperation.

The reader knows very well that there is suffering in the world, and most of us would wish to end it. We unfortunately inhabit in a world that is constantly trying to kill us. Not all interests, long-term or short-term, can be realized all the time; some are impossible to achieve, some are incompatible with others, and some are cut short by death. We should always act to be the good Samaritan. Surely I cannot witness an injured man on the side of the road, and pass on the others side saying, “not my problem, besides I’m late for work” But I also can’t take the world’s burdens upon my shoulders.

So although it may be good to contribute to a certain cause, it’s not wrong not to, under certain circumstances. This means that we must carefully decide which circumstances are special cases, and which circumstances should be a general rule. What actions create the most overall good with the least amount of suffering? How can we create a profit of happiness for the most amount of people in the world? How can we allow the greatest number of interests for the greatest number of people? Those are the questions we must ask. This is our general rule.

We must remember, the best societies thrive on mutualism, because mutualism increases overall happiness in the world, rather than simply shifting it from one place to another. When a ship begins to sink, we don’t force the ship’s crew and staff to sink with it so that the paying passengers may escape to safety. We don’t trample each other in a stampede, or confer to the other, “after you, kind sir.” We attempt to unload as many people as possible, and although everyone may not find safety, the loss will be far less than it would have been any other way.

Hope you're enjoying this series. Stay tuned for more.

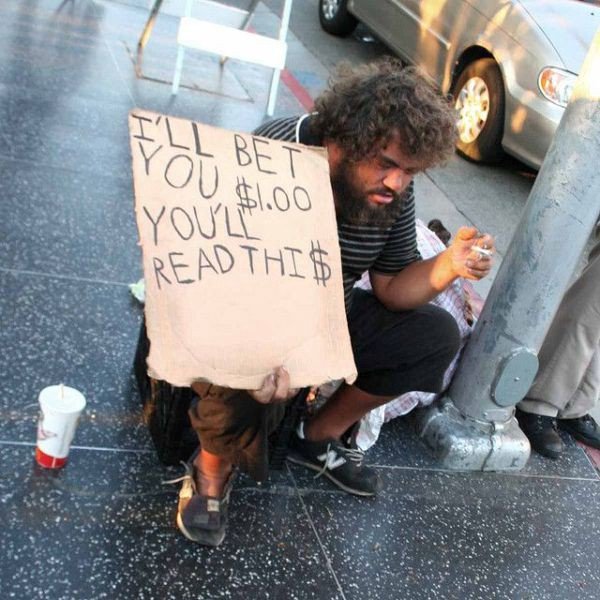

My personal motto, more or less...

"Right and Wrong and divided by harm, weighted by responsibility, and balanced by intent."

following. @originalworks

To call @OriginalWorks, simply reply to any post with @originalworks or !originalworks in your message!

For more information, Click Here! || Click here to participate in the @OriginalWorks writing contest!

To enter this post into the daily RESTEEM contest, upvote this comment! The user with the most upvotes on their @OriginalWorks comment will win!Special thanks to @reggaemuffin for being a supporter! Vote him as a witness to help make Steemit a better place!