On October 10, 1918, a strange group of people gathered on Merion Green at Bryn Mawr College. Members of the Christian Association covered their bodies with masks, gowns, and other costumes, and instead of shaking others' hands, they extended yardsticks in their classmates' direction. This was the "anti-flu party," and it was one attempt to carry on with campus life during the school's heavy quarantine.

Merion Green, Bryn Mawr College. Image courtesy of Bryn Mawr College.

Keeping Students Safe

Bryn Mawr College, a small women's college located just outside Philadelphia, instituted a quarantine that, despite 110 flu cases reported, saw 0 fatalities. The president, M. Carey Thomas, was familiar with the science of the time regarding the epidemic and instituted the quarantine to prevent the spread of disease. As early as the first reported case, on September 26, she wrote to a colleague about how it was a problem that others were visiting the sick student. Shortly after, her quarantine banned all students from crossing Montgomery Ave, taking trains, and coming to school at all if they lived off-campus. Faculty living off-campus, external speakers, and relatives of healthy students also could not come to campus.

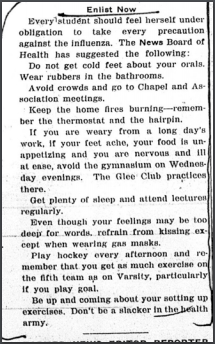

Bryn Mawr College News, October 2, 1918. Enlist in the health army!

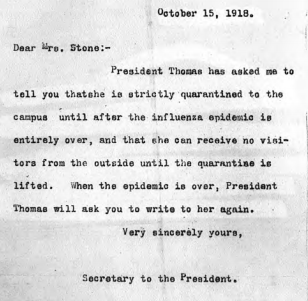

As the disease progressed, so did the quarantine. Thomas implemented more and more restrictions, required all students and faculty to get vaccinations, and even included herself in the quarantine.

M. Thomas (via secretary) to M. Stone, October 15, 1918

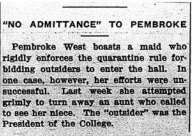

College staff also helped to make sure the quarantine was diligently followed.

Bryn Mawr College News, November 7, 1918

A Successful Quarantine?

Despite the meticulousness of Thomas in implementing her quarantine, not everyone followed it. On October 17, a Lost & Found column listed one student who had "had never heard of quarantine regulations." The column explained that "she escaped all conversational references to these college interests owing to the fact that she was spending most of her time in the labyrinths of Wanamaker's."

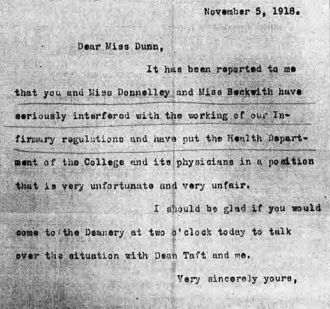

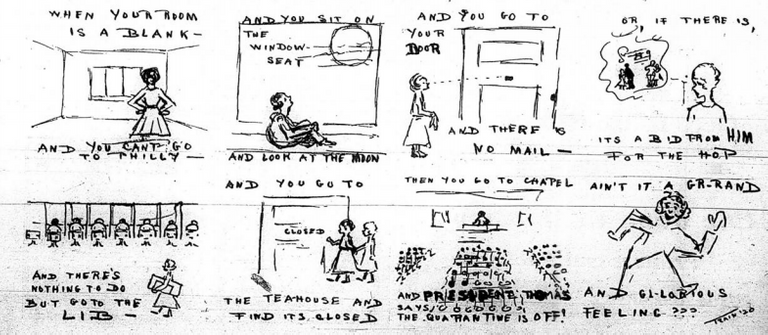

Students bristled against the restrictions, with one student journalist describing how the college has been "violently cut off" from all infusions of outside life." Thomas repeatedly reprimanded students for breaking the quarantine, such as on November 2, when she discovered students sleeping in a dorm other than their own, and on November 5, when two people mysteriously put the college's Department of Health into an unwanted position. The college's health department at this point was so packed that even Thomas herself assisted doctors and nurses in caring for sick students.

M. Thomas to A. Dunn, November 5, 1918. What did they do???

Others attempted to carry on with the college's many traditions, such as Lantern Night, typically held in early November.

Bryn Mawr College News, November 7, 1918. During Lantern Night,

freshmen are officially welcomed into the college by ceremoniously

receiving colored lanterns that represent their cohort.

An End in Sight

By the second week of November, the quarantine began to be slowly lifted, and the campus gradually returned to normal. To celebrate, students flocked to Philadelphia, partied outside, and even convinced the school to cancel classes.

Bryn Mawr College News, November 7, 1918

So what?

When we learn about the past, so often we focus on major players. Regarding the Spanish flu, studies often focus on heroes like the nurses and humanitarians, the victims, or villains like Wilmer Krusen. Less often studied is the general populace — how did ordinary people withstand and survive the disease itself and an atmosphere saturated with death and tragedy?

Bryn Mawr students proudly sing about fighting not just for their bread, but for roses too. M. Carey Thomas successfully fought for students' "bread" through her strict quarantines protecting students. And by attempting to hold onto a semblance of normal life during a very abnormal time, students had their roses too.

Sources:

All documents from the collections of Bryn Mawr College Library, Bryn Mawr, PA.

For more information, click here.

Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's

Congratulations @charliehersh! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPNice work. As we keep up this exploration of 1918, we begin to delineate the many types of narratives available to us and the various classifications of information we choose to make. I wonder what a diagram of it all would look like?

Oh my goodness, I love that comic so much!

I tried to explore different archives rather than online newspapers this time, but couldn't find anything that really grabbed my interest. Great job finding these!

Omg yes isn't the comic great :D

Thanks! Honestly I stumbled onto these by accident... I was actually planning a piece on the commencement speech given at Gratz College in spring 1919 and I was trying to research if they'd supported any humanitarian efforts during the epidemic and came across UMich's finding aid instead...

But I agree that newspapers are so much more convenient for this type of research, especially when primarily researching digitized documents (because who has time to actually go to physical archives, lol).