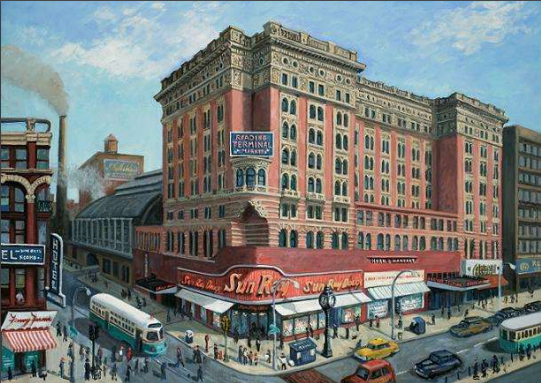

One of the prospective locations for the proposed History Center in Philadelphia was here, at 12th and Market Street.

In recent weeks, one of our assigned readings was the Vision Statement for a Philadelphia History Center. I wrote a response to said reading here, if you would like some context. The idea behind that History Center (which it should be noted, never came to fruition) was to provide a central hub for Philadelphians and visitors to learn about all facets and eras of Philadelphia’s history, not just the Revolutionary and Early Republic eras which are revived into vogue roughly every 50 years. I have thoughts on that, but that’s for another post. Anyway, the idea was that the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the Atwater Kent Museum (now the Philadelphia History Museum) would work together to create this museum.

The readings for this week provided additional context around that proposal, specifically from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s (hereinafter the “Society”) side of things. By the 1990s, some folks in the Society were realizing that business as usual was not as profitable for the research institute and museum and more importantly, that some choices needed to be made. When the Society hired Susan Stitt as their new CEO and president in 1990 – and as their first female CEO and president I should add – she threw herself into examining the organization’s spending and capitalization abilities, and committed herself fully to making some of those tough choices. After two years of such examinations, and after reducing and restructuring the Society’s staff, she summoned the Board together in late November 1992, to present her findings and three suggestions for a path forward.

A photograph of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, one of the country's most prominent research libraries.

The first two options were fairly simple. The first option was to live within their current means and go on as usual. I interpreted this as moving forward and just hoping for the best. The second option was to maintain the Society’s identity as a research library and deaccession their artifacts to other nonprofit institutions. This would allow the Society to restructure around their core identity without struggling to have the best of both worlds.

The third option was the most radical, and Stitt intended it as such. This option was the “big idea” option, whereby HSP would maintain its core identity as a research library, but instead of just deaccessioning their artifacts, HSP would partner with other cultural institutions to fund and create a major history museum. This history museum was the aforementioned Philadelphia History Center. According to the case study from Woerner and Greyser, before presenting this to the Board, Stitt ran her idea by foundations like the Pew Charitable Trusts, William Penn Foundation, and the Annenberg Foundation and was met with positive responses.

A photograph of the Philadelphia History Museum, formerly called the Atwater Kent Museum, on S. 7th Street.

Stitt was met with resistance, of course, but the project went forward. As we already know, the Philadelphia History Center never happened, and in 1999, several years later, HSP deaccessioned its artifacts to the Atwater Kent Museum (again, now the Philly History Museum. Since reading about the failed Philadelphia History Center several weeks ago, I have argued that it might have been in the best interest for both HSP and the Atwater Kent Museum to simply allocate the $50 million to the Atwater Kent, as their mission lined up closely with that of the proposed History Center. The 10,000 new artifacts that the Atwater Kent received could have been wildly beneficial for them in creating new educational programming and exhibitions to increase their attendance, but alas, that did not really happen either.

So what are we to make of this, dear reader? My personal opinion is that the HSP made a brave and innovative choice to follow option 3, even if it didn’t pan out as planned, and I certainly agree with their decision to deaccession their materials to the Atwater Kent Museum. How could we apply these decades old decisions to present day cultural nonprofits? Is it always best to make risky but potentially lucrative decisions? How do we know when we need to go back to our roots and reexamine our organization’s core missions, as HSP did? Are there any cultural nonprofits you know of that could benefit from such a combination of introspection and dedication to change? Let me know in the comments below!

click here.100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more

Sources:

Stephen A. Greyser and Stephanie Woerner, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. (Harvard Business School case study) November 20, 1996, revised February 5, 1997.

Agreement Between Historical Society and Atwater Kent Museum, 1999.

The Vision for a History Center in Philadelphia (1996).