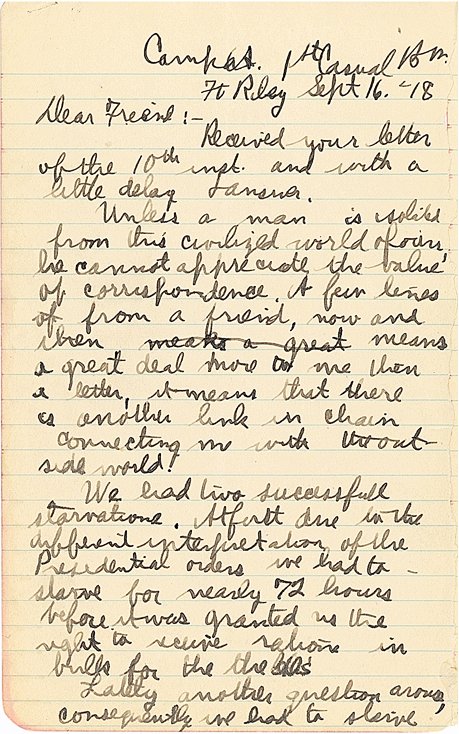

"Camp 1st Casual Btn.

Ft. RileySept. 16, '18

Dear Friend:

Received your letter of the 10th inst. and with a little delay I answer.Unless a man is isolated from this civilized world of ours, he cannot appreciate the value of correspondence. A few lines from a friend, now and then means a great deal more to me than a letter, it means that there is another link in chain connecting me with the outside world.

We had two successfull [sic] starvations. At first due to the different interpretation of the Presidential orders we had to starve nearly 72 hours before it was granted us the right to receive rations in bulk for the CO's.

Lately another question arose, consequently we had to starve..."

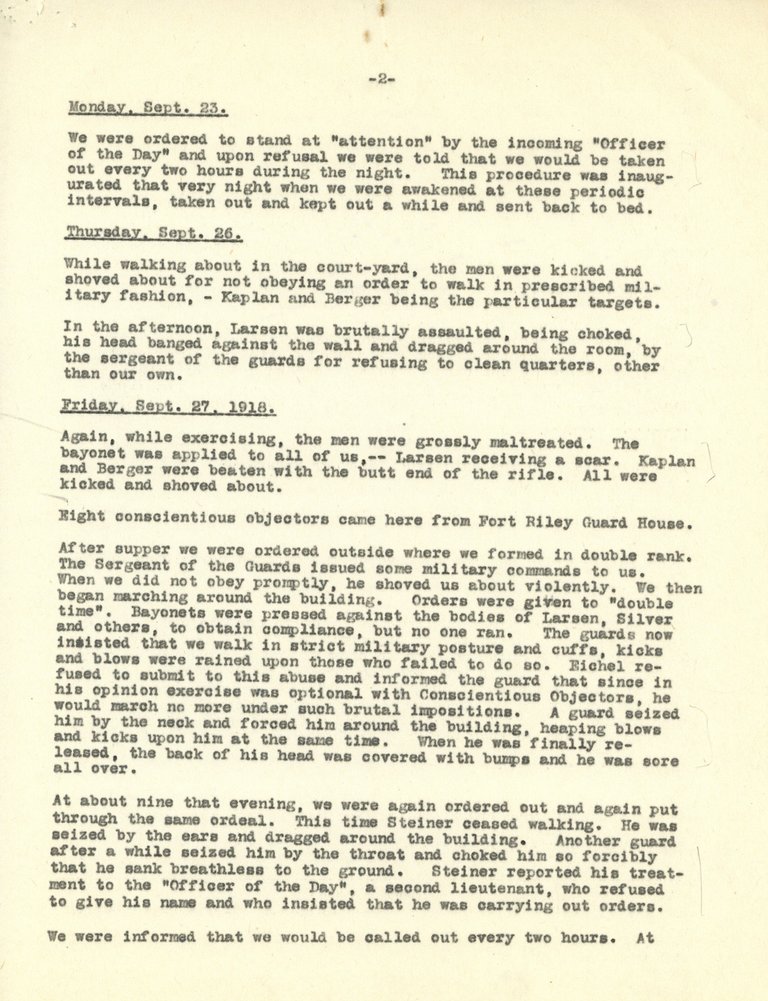

So begins a letter from Ulysses DeRosa from his quarters at Fort Riley in Kansas.[1] He and others like him were embarking on hunger strikes in military prison. Their charge? Willfully disobeying orders as a symbol of their conscientious objection. DeRosa was one of 19 conscientious objectors held at Camp Funston[2] within Fort Riley, and they detailed their mistreatment--primarily beatings, denial of mail and packages--in a 10-page report. Here's page 2:

These men objected to warfare for various reasons. DeRosa had become a Quaker two years before and like members of other peace churches such as Mennonites and Amish espoused a non-resistant theology. Others lodged their opposition to war because of socialist or humanitarian beliefs. The 19 at Fort Riley were not alone. During World War I, 450 Americans were found guilty in military hearings because of their conscientious objection, receiving sentences ranging from short prison sentences to death (17 individuals).[3] Some, such as two young Hutterite men from South Dakota, imprisoned at Alcatraz and Fort Leavenworth, died during their incarceration.[4]

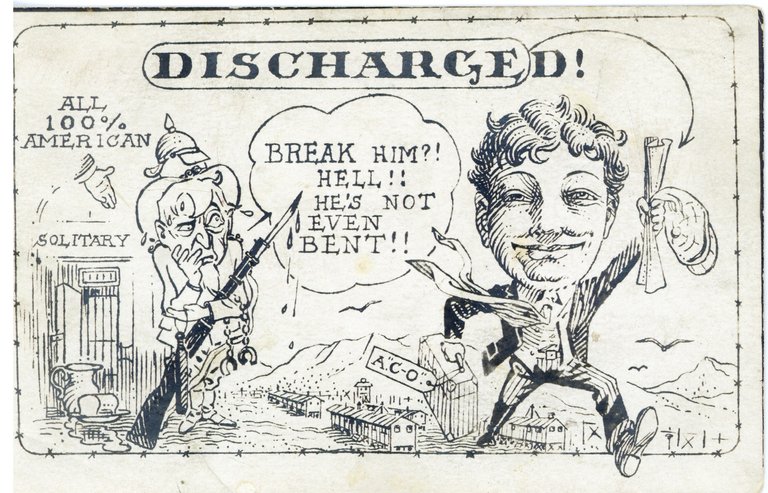

A postcard ca. 1919 shows a resilient CO emerging from solitary confinement

Many of the commemorations marking the events of a century ago will focus on the Great War and those who were willing to show what they believed in on the battlefield, but I think it is just as important to remember those who acted out their beliefs behind the bars of military prisons on the home front.

Notes:

[1] These documents are part of "Conscientious Objection and the Great War," a digital project of the Swarthmore College Peace Collection

[2] Camp Funston had already made its mark on 1918 by the time DeRosa arrived, having been the site of one of the first outbreaks of the deadly flu of that year. For more, see John M. Barry, The Great Influenza.

[3] Statistics via PBS.

[4] This story is told in more detail in Duane Stoltzfus, Pacifists in Chains from Johns Hopkins press.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.

Nice post! And I agree with you -- it's important that many Americans had (and still have) reasons to not support wars, especially wars that are typically remembered through a triumphalist or good-versus-evil lens.

Interesting, thorough and nicely documented with primary sources. Was WWI the start of the CO status in the US, or did it appear on the homefront during earlier wars?

There were informal exemptions as far back as the Civil War. My understanding is that it was the cruelty shown to COs in WWI that got the historic peace churches and other pacifist groups to organize alternative service organizations by the time of WWII.