"A coming realization"

In the summer of 1918, James Lynn Barnard and Jessie Campbell Evans sat down to compose the preface of their book, Citizenship in Philadelphia.[1] In three hundred and seventy-six pages, Barnard and Evans covered a broad spectrum of civic activities, privileges, and responsibilities. The table of contents lists chapters not only on broad concepts such as "Health" and "Transportation," but also "Street Cleaning and Waste Disposal" and "Police, Accidents, Weights and Measures."

Having consulted various city officials and drawn on years of experience teaching civics, including in Philadelphia's elementary schools and compiled their findings, the authors made their case for why this book should exist.

"There is visible everywhere in the United States an increasing interest in public welfare and in city government which has so much to do with securing it," they began (7). "As a part of this new order of things there is coming a

realization of the simple but important truth that the primary object of civic teaching is, after all, to make good citizens."

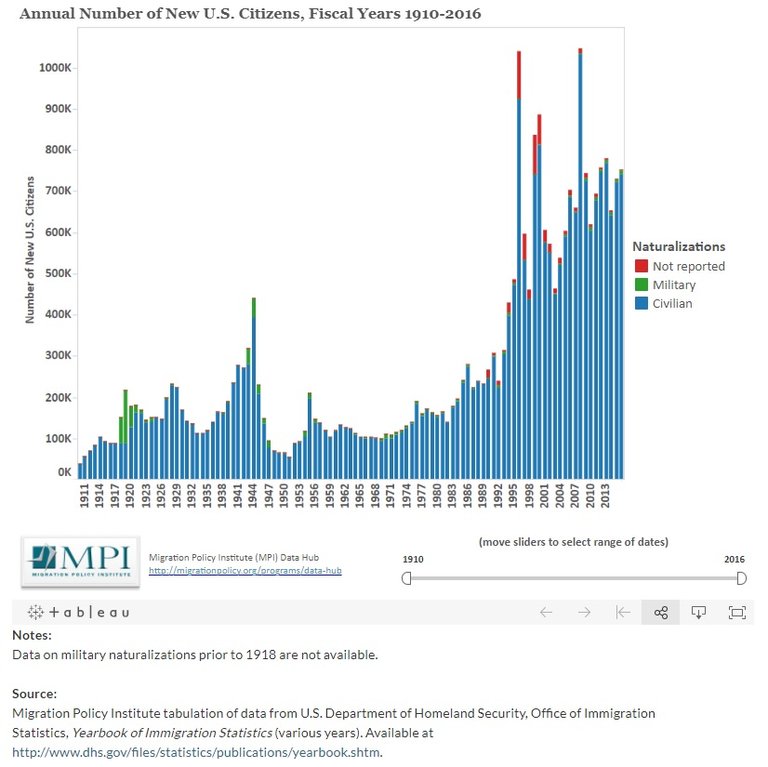

What was the source of this "new order," that brought "increasing interest in public welfare"? Immigration. Check out the steep increase in naturalization just before World War I brought in a bunch of military naturalizations.

[2]

[2]

Declension and Progress

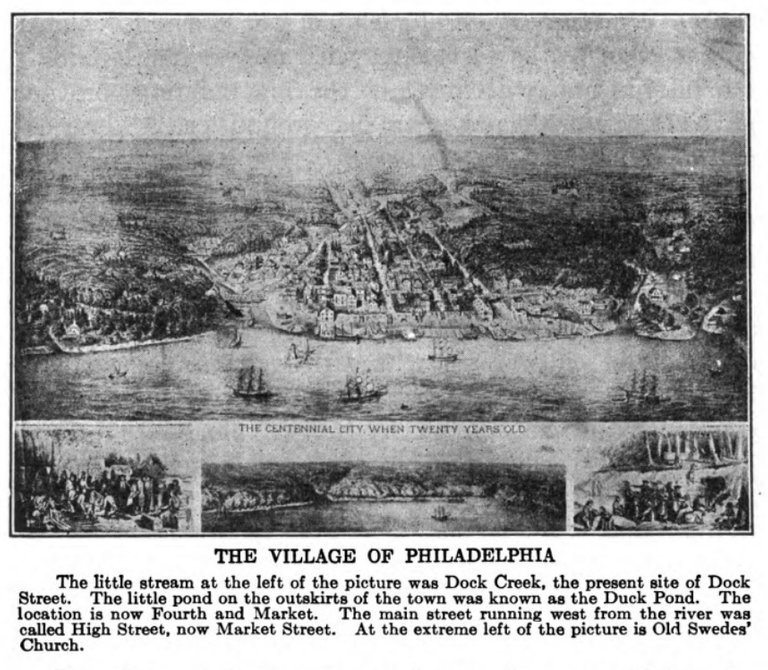

So what did Citizenship in Philadelphia teach immigrants and their children? Barnard and Evans began with the history of Philadelphia. An illustration of "The Village of Philadelphia" showed the city's origins; a depiction of Independence Hall showed the origins of the nation.

Using the imagery colonial and revolutionary America was hardly a groundbreaking rhetorical move here, and it was to become more common. Many of the early house museums of the United States reconstructed early America as an educational space, sometimes very explicitly aimed at newly-arrived immigrants. For instance, Orchard House, the childhood home of Louisa May Alcott, was "restored" as a teaching tool for the children of immigrants in 1912.[3] In New York, settlement houses sponsored tours of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's period room for new immigrants.[4]

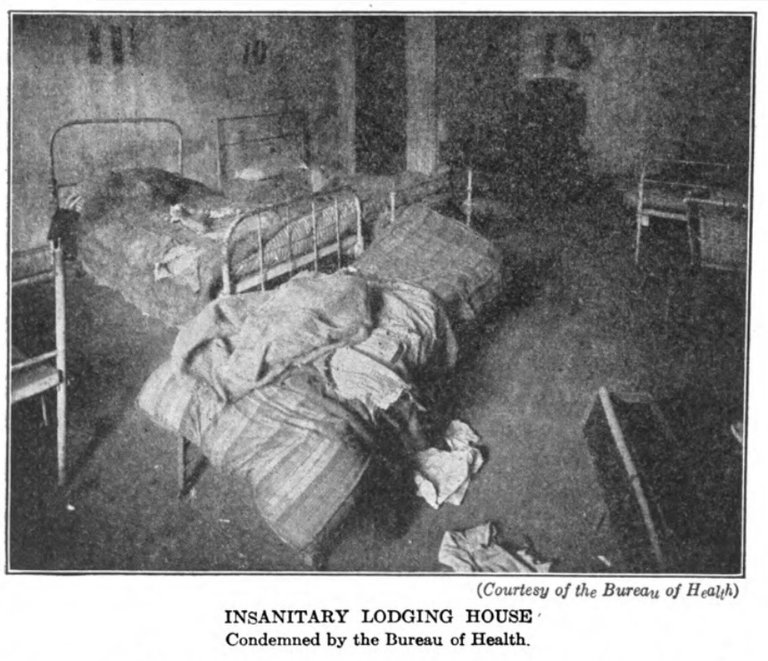

If Chapter 1 looked backwards, Chapter 2 - Health espoused the most current theories about clean food, water, and humans' need for "fresh air and light" (34). The illustrations in this chapter were of a bilk bottle with troubling sediment and an "insanitary" tenement.

Hygiene had entered the public school curriculum in response to various public health crises, along with periodic health screenings and dentist checkups.[5]

Law and Order

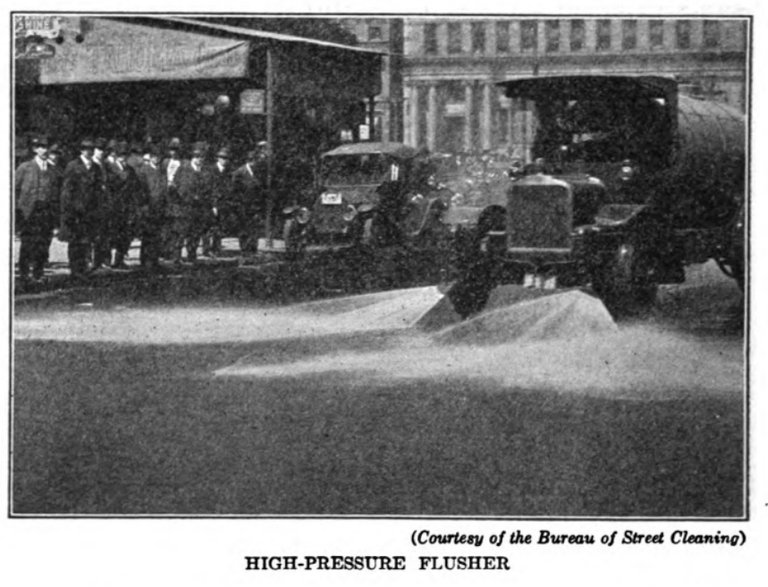

In the chapter on street cleaning, citizens were advised:

To Avoid Error--Know the Law

To Avoid The Penalty--Obey the Law

The section on law enforcement also outlines some of the city's legislation and explains the purpose of the Department of Weights and Measures. It seems that five years before this book was published, when Weights and Measures was created, it was in response to the ubiquity of deception on the part of shopkeepers as they measured out merchandise for customers.

"Literally Hundreds of Other Schools"

Running through most of the book, from the description of trade and home-making instruction in the public schools to the plans for the nascent Parkway with the new home of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, from the libraries throughout the city to the many colleges and universities, is an emphasis on education as a form of uplift. In my cursory reading of this text, it seems that this is the main theme. Barnard and Evans saw education of the citizenry as a path to a more perfect city, a sentiment I applaud even as I suspect that some of the rhetoric in the broader conversation around citizenship veered into paternalism.

What can Philadelphia in 2018 Learn from 1918?

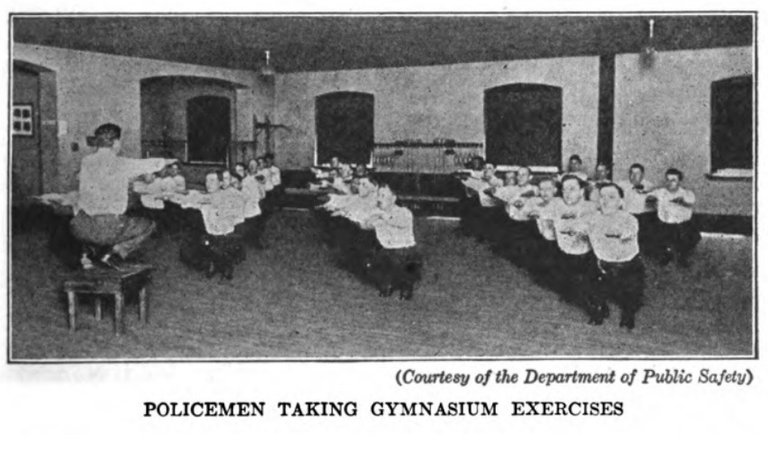

Bring these back!

Notes

[1] All quotations and images (except for the graph) from James Lynn Barnard and Jessie Campbell Evans,James Lynn Barnard and Jessie Campbell Evans, Citizenship in Philadelphia, 376 p. (Philadelphia: John C. Winston Co., 1918), accessed via the Hathi Trust: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008677277.

[2] Migration Policy Institute tabulation of data from U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (various years). Available at http://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/yearbook.shtm.

[3] Patricia West, Domesticating History: The Political Origins of America’s House Museums (Washington [D.C.]: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999).

[4] Seth C. Bruggeman, Here, George Washington Was Born: Memory, Material Culture, and the Public History of a National Monument (Athens, UNITED STATES: University of Georgia Press, 2008), 62.

[5] Of course it was just a month after the book was published that the flu hit Philadelphia.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.

I'm trying to imagine someone actually buying this book to consult. My suspicion is that lots of them ended up dusty on library shelves!

This is definitely an interesting topic, Ted. How far can schools go to promote hygiene without becoming overly paternalistic? Interesting to see that the city was struggling with similar questions 100 years ago.