When he filmed the movie Day of the Fight (1951), Stanley Kubrick first began to think about music in his films. However, it was not his first encounter with music. At the school he played percussion at the orchestra, but other members of the orchestra complained that he didn't follow what was happening because he was more interested in the camera he always carried around. But when he became a member of the newly established The Swing Band, which performed popular melodies and played on school dances (The Swing Band consisted of Shelly Gold - saxophone, Bobby Sandelman - Clarinet and Tenor Saxophone, Stanley Kubrick - Drums and Eydie Gormé - Singer ), he become more focused. "... He came to practice and play," his friend and colleague Bobby Sandelman remembers . "He was most prominent when he played swing, jazz or contemporary music. He didn't carry the camera on the reharsels anymore. We caught his attention, and we got the entire Stanley Kubrick, not just his part. He was a good drummer. He was more than "metronome."

In the documentary Day of the Fight, Kubrick didn't want to use the so-called "archive music'', but - unusual for a documentary - he started searching for a composer. The quest ended with the discovery of schoolmate Gerald Fried, who became a "permanent" composer of his early films. However, music for the next documentary film that Kubrick recorded the same year, Flying Father (Flying Padre, 1951), was composed by a relatively unknown Nathaniel Shilkret, but Gerald Fried composed for all the following films by Stanley Kubrick - Fear and Desire (1953), Killer's Kiss (1955), The Killing (1956) and Paths of Glory (1957) - all the way to Spartacus (1960), for which music was composed by far more elite composer Alex North.

(Stanley Kubrick plays drums with members of the George Lewis Ragtime Jazz Band of New Orleans in George Lewis’ backyard, as photographed by music critic Joseph Roddy, New Orleans, 1950)

(Stanley Kubrick plays drums with members of the George Lewis Ragtime Jazz Band of New Orleans in George Lewis’ backyard, as photographed by music critic Joseph Roddy, New Orleans, 1950)

Spartacus was filmed under the supervision of Universal and the film company Bryna, with which, from film Paths of glory, Kubrick and his producer James B. Harris had a cooperation agreement for the next five films .

Large amount of money was invested (the largest ever in Kubrick's career), was looking for some victims - among them probably was the choice of the composer. But it is possible that Kubrick felt that Fried's composing style, totally unknown in Hollywood, would not match the typical Hollywood movie.

It is also possible that the filmmaker decided to take the opportunity to duly 'release' a solid, but not excellent composer who, after all, cooperated with Kubrick, and continued to work on composing film and television music.

Kubrick developed rapidly and he was always interested in the same things: war, human behavior, pessimism, destiny, life in urban environments, hierarchies within various (military, social) human arrangements. This is seen in the selection of film genres: two are from the first four films of war (Fear and Desire, Paths of Glory), and two belong to the later repertoire of the movie noir (Killer's Kiss, The Killing). From film to film, it became clearer that Kubrick was in a style that was far from classical. Research of human behavior, mirroring of antagonistic characters (equalizing 'good' and 'evil'), emphasis on the role of the case in human destinies and the grotesque depiction of individual scenes (death, for example) - all had to be reflected in music.

First Phase: Gerald Fried

With Fried, Kubrick began to co-operate as a beginer director. His ambitions were great (hence allegory-psychological-poetic themes of the first feature film Fear and Desire) but had no experience. Having mastered the on-going film technique (he never started film school and studied all the movies that were screened at theaters), he chose the first composer as he chose actors and other collaborators - according to the principle of acquaintance. Kubrick's call was also a surprise for by Frieda himself, who was an orchestral musician at that time. For Fear and Desire, Fried wrote a very contemporary piece, but his problem was the medium. Like a 'free' musician, he was thinking of the audience in a concert hall rather than a movie audience who does not listen to music but watches the movie. The composer approached each scene separately, which probably slowed down the work and did not produce the desired results. Music existed with the film, but not in the film - like a 'foreign body' or a 'parallel world'.

Fear and Desire (1953)

Fear and Desire (1953)

However, Kubrick left the composer alone in the first feature film. Already in the next movie, Killer's Kiss , he asked that Fried, with the original composing music, also use non-original music. Song ''Once'' by Norman Gimbel and Ardennes Clara he saw as a love theme, so Fried's job was to "obscure" the song , without the help of film scenes, and write a number of instrumental versions. The song Once was in the way to repeat the problem of music as a 'foreign body' from the previous film: it was neither film-composed nor instrumental rework for certain film scenes. But this time Kubrick directly took over the direction of music. Turning Gerald Fried into a penny arranger, he himself chose music arrangements, which he 'drank' under certain scenes (which he also chose).

Killer's Kiss , therefore, also in the musical plan confirmed Kubrick's need to control all film elements. Since he did not know how to compose, the film was 'embarrassed' by using the popular song.

Paths of Glory - the best score by Geralda Frieda

The opposition between order-disorder will appear again in the film Paths of Glory. Returning to the theme of war, like in Fear and Desire, Kubrick sought to show how the war 'friends' and 'enemies' are equal. He did so by focusing on only one side, the French side and turning the "enemies" (Germans) into phantoms, which are mostly irrelevant to the movie story. Namely, on only one side of the war there are hierarchical divisions, 'positives' and 'bad guys'. The officers / gods / soldiers / insects in the movie are divided by music: first enjoy the luxurious halls of French castles and are dancing to the rhythm of the waltz by Johann Strauss, while others are left with the horrors of war trenches where blaring of military drums turns into unsworn music and stap with sounds of explosions and bullets.

Stanley Kubrick on the set of Paths of Glory (1957)

This is probably the best score by Gerald Fried for Stanley Kubrick. It combines the ideas from earlier films: converting realistic sounds to music (as in the final scene at the station in the Killer's Kiss), the use of a percussion as an unpleasant warning element and the use of unoriginal music as an important film element (the song One from Killer's Kisaa corresponds to the song Vjerni Husar at the end of Paths of Glory, and there are also the motifs of the French hymn incorporated into the composing introductory music).

The idea of structuring film scenes for music, which was felt in the Killer's Kiss, eventually formed a scene from the Paths of Glory where Colonel Dax prays the lives of the convicted to General Broulard, and in the background the Waltz is heard. All of these elements lead to another important function of music that will become common in Kubrick films - the function of ironic contrapunt.

(Paths of Glory, 1957)

(Paths of Glory, 1957)

Second phase: Alex North and the rest

Spartacus score, composed by prominent Alex North, is the best example of why Kubrick didn't want standard movie music. Namely, linking similar characters to related legitimate motifs or transformations of a theme within a stylized unified compositional language didn't allow for musical unusualness that would be consistent with the director's growing need for exploration (apart from the unusual use of music, Kubrick explored themes and motives such as pessimism, grotesque, coincidence, unusual human behavior and death). Kubrick liked the extremes, liked to use the music that sometimes 'grabs' the viewer and makes him wonder why. This was not possible with conventional film music that traditionally didn't have to 'bother' the scene, which had to be 'invisible' and 'silent'. Kubrick had to reject all the typical features of classical movie music (the most classic in his opus was the North's Spartacus score) to achieve a special, yet unexplored, action.

Still, Spartacus was not just a mere 'outsider' in canon. The leaning games with music that, like in the silent film, played at shooting, creating a mood for actors, as well as games for the set-top desk where even the music from the Chaplin movie City Lights was found in the Spartacus scenes show (that music was clearly not used in the final version)

All these were preparations for future movies. Lolita (1962) shows how the genre and style of music was not of any interest to Kubrick. Riddle had to compose a very romantic, clearly thematically designed partitur for pedophile Humber, but also had to create an unusually dissonant, atmospheric music for kinky Quilty (it is interesting that this music almost covers the "weird" pentathonic music number underlined the homosexual tendencies of Mark Kras and Antonin in the bathing scene that the censors had cut out of the Spartacus film).

All this shows Kubrick's tendency for the most diverse musical genres, as well as his desire to closely monitor what is happening with current movie music. He was interested in the use of the song as an excess, as a music that would catch the audience so much that they would remember it for a long time. That's why in Lolita he used the instrumental by Bob Harris.

In his next film, Dr. Strangelove (1964) he went a step further. Kubrick for the first time in the film, implements the meaning of the text that, like jazz in earlier films, serves as an ironic commentary. Even for the songs that were instrumented it was important to know the text. If instrumental versions of the song commented on the scenes by pointing to the comic, the song Vere Lynn We'll meet again, come up with a prominent text (in the final scene of chain nuclear explosions) that brought something to Kubrick: a sharp contrast to the meaning of the song's text (Vera Lynn sings: We will meet again, who knows when, who knows where) and the content of the scenes ('Judgment Day' - because of a series of nuclear explosions humanity came to an end). It is a contrast that Kubrick will not use solely for the purpose of parody, ironism, and grotesque approach, but also to encourage viewers to review prejudices, norms, and firmly establish views.

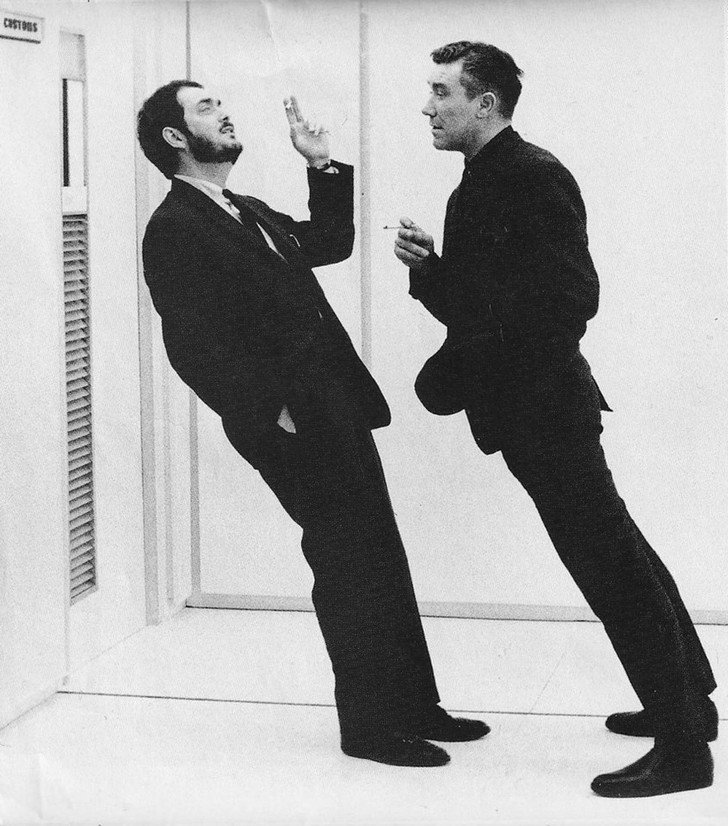

George C. Scott and Stanley Kubrick playing chess on set.

George C. Scott and Stanley Kubrick playing chess on set.

Third Phase: Rejection

With Alex North begins 'the story on film music'. When he dropped North's 48-minute (ordered!) Scores for 2001: Sapce Odyssey and decided to use music from classical music literature, Kubrick broke several 'unwritten rules'. Instead of the existing original film music, he used the original 'nonfilm' (classical) music to be used only if the first one did not exist. But the original movie score existed, so Kubrick, casting it off, brought the anger of not only Alex North, but all the prominent film composers and their fans. Anger was justified and because the principle of 'joining' classical, non-original music and scenes was, in fact, the case principle.

The problem was, therefore, the respect which was neglected, but the problem was also the classical music use in the film. Why did that happen at all?

One of the answers is that Kubrick was gradually maturing. His accentuated need for full authorship from the beginning has encompassed numerous film aspects: writing scripts, recording, editing, production, and more. And now he has been trying to expand on more demanding film elements, especially on music (which is more demanding because he asks for the specific education that the director did not have, despite the "practice" in The Swing Band). The beginning of the establishment of total control was the discarding of North's scores, and the use of earlier composing classical literary music in a completely specific, unexpected way. For the use of classical music in 2001: Space Odyssey would not be anything new if there wasn't for Kubrick's totally individualized connection between music and the scene. This connection was completely different from the one established by the tradition.

Stanley Kubrick's 2001: Space Odyssey gave new meaning to the concept of music and scenes counterpoint.

Kubrick defying Gravity on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey

Note: This is my translation from Croatian to English, article Hrvatskog Filmskog Saveza ''Stanley Kubrick i filmska glazba, ili put prema glazbenom izboru u 2001:Odiseja u Svemiru'' , I. Paulus

great movie and good story ❤️🌸

I love absolutely love Kubrick so you get my vote and resteem. I'll have to read your post properly when I'm home, as I'm just about to jump out of a taxi :p

haha, thank you!

I think you will really enjoy it :)@steemmeupscotty

Yes, you've written a thoroughly enjoyable piece @marinauzelac, and I think you've connected the dots of why I love Kubrick so much. I've never been able to listen to 'Singing in the rain' the same way after watching 'A Clockwork Orange' all those years ago :)

yeah, just like Vera Lynn's ''We will meet again'' :)@steemmeupscotty

Yup ;) Even nuclear holocausts need a soundtrack!

fascinating topic, i've never considered the relation of kubrick to music, beyond the obvious score of 2001. stanley is amazing but often to emotionally violent and shocking for my tastes, but obviously a genius.

He is a total control freak, everything in his movies is there for a purpose. He's a maniac :)@clumsysilverdad

Very interesting essay, thanks for the translation!

Also shared on twitter.

Saving this one for later. Looks interesting, thanks! :)