If there is a technological singularity, whoever comes after us will look forward to other singularities.

The Ordinary Course of Revolution

When Newton published the Principia, he was apotheosized.

To quote Pope's eulogy:

Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night:

God said, "Let Newton be!" and all was light.

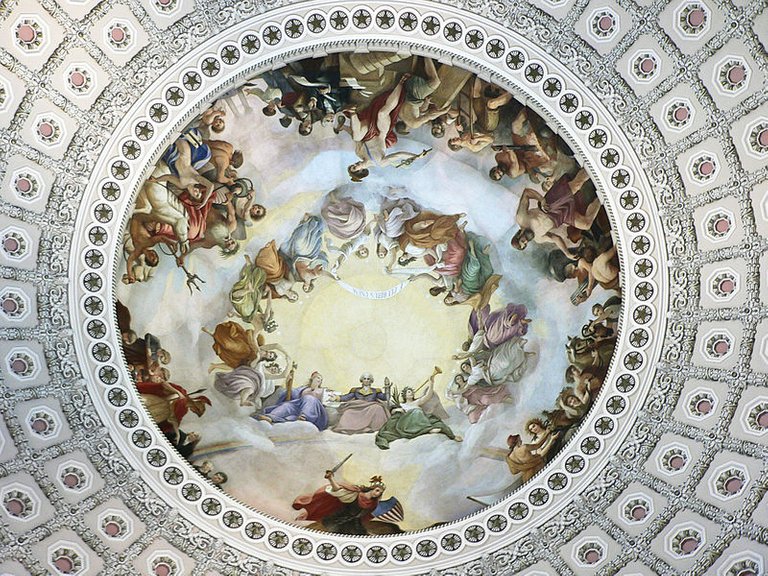

On the ceiling of the rotunda of the United States Capitol, there is a large

painting called The Apotheosis of George Washington, showing the great man

seated in the clouds, clad in a Roman toga, having become a sort of demiurge.

I mean, that painting is absurd, and that's what happened to Newton. The

god-like intellect, which o'er the cosmos casts its eye of light, that sort of

thing.

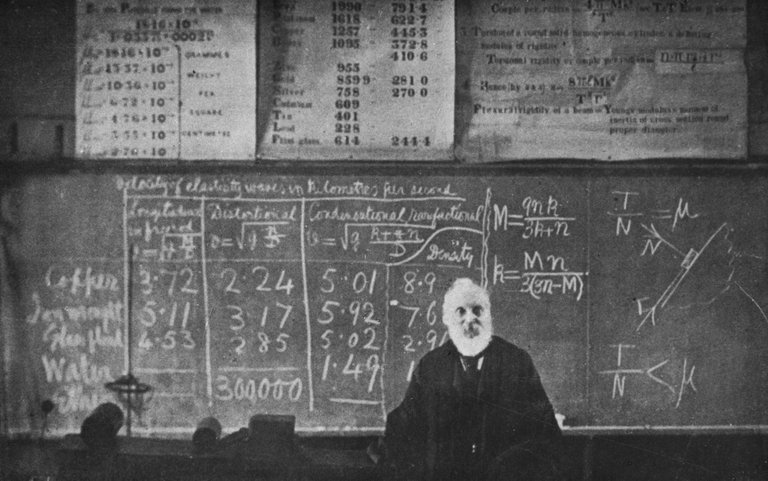

A similar kind of shock and awe overtook the Western world during the Industrial

Revolution. Mendeleev's table had come out in 1869, Lovelace and Babbage and

Boole were at work, Maxwell and Heaviside and Gibbs back in America were working

out statistical mechanics and vector calculus. Lord Kelvin thought there were no

more physical laws to discover. You get the sense that the scientists in the

late Victorian Age were just overcome with how much they knew, how much they'd

discovered in such a short time.

Then, of course, Einstein, Bohr, Gödel, Turing, von Neumann struck. Again,

Einstein in particular became a massive celebrity, the one who had unlocked the

secrets of the universe.

By that time, Kuhn and Popper and others had enough historical data to begin to

think about the process of scientific revolutions. These worldview-shattering,

humanity-altering scientific discoveries were to be somewhat… expected.

The scientific community in general became more adept at thinking about

uncertainty in their theories. The vocabulary of models took over, a key change,

because we can think about a model being more accurate than the previous model,

while at the same time permitting uncertainty and the possibility that the

model, and the larger scientific model or paradigm within which it is situated,

may need to be fundamentally revised.

I think few of us look back wistfully to the days of Newton or Kelvin, those

first heady days of humanity's discovery of somewhat-accurate principles of the

cosmos, and wish we still felt that certainty that we now knew all there was to

know. We're happy to watch the ongoing process of scientific discovery and we

hope every year for a new paradigmatic revolution, a tectonic plate theory that

will upend all we know.

We have relativized these revolutions. We have placed them within a loosely

Hegelian framework of continuing intellectual progress. Our meta-model, if you

will, of the scientific process which constructs all our scientific models, now

embraces revolution as the ordinary course of scientific work.

We honor Crick and Watson, but we do not apotheosize them. No clouds and togas

for them! Our awe at the shocks to our intellectual girdings has diminished.

This is to the good, because we can think more sensibly about how to find the

next revolutionary idea, and about what comes after the world-shattering idea.

The Technological Singularity

Almost as soon as we realized that thought itself could be constructed from

smaller, deterministically-programmed parts, we deduced that thinking machines

might one day think and feel all that we do, but bigger and faster. The Industrial

Revolution would move into mental work, just as powerfully as machines took over

physical labor but perhaps more precisely.

The implications of that deduction lay dormant in popular discourse for

awhile. Since deep learning became a viable technique about 2006, thanks to

Moore's Law and huge amounts of data on which to train our algorithms, Silicon

Valley has renewed its debate over the future possibilities of AI.

Roughly put, the field is divided between those who believe we can design a

superhuman general intelligence that is friendly to humans, those who point out

the weak have never been able to control the strong, and those who believe we

will unite with our machines to become silicon-carbon cyborgs.

As a result, we are currently discussing our latest world-altering intellectual

revolution. Unlike previous revolutions, the idea of a technological singularity

is more technological than scientific, but there's a similar sense that "this

could change everything," a similarly apocalyptic tone.

The debate is eschatological or apocalyptic not only in the fear that we might

not survive it, but also in the sense that a technological singularity would

mean the end of intellectual history, in a sense. If it comes, it comes, and

then everything we've done will be dwarfed. What more is there to say?

A Word with Our Descendants

I don't know which scenario is more likely. If we are all wiped out, though,

there's not much to say to the machines or organisms which succeed us and spread

through the cosmos.

Let us imagine, then, that our successors are something we recognize. Perhaps

they are more-or-less normal humans, longer-lived and served by

quasi-intelligent machines. Perhaps they are cyborgs, traces of humans who have

evolved and merged into something beyond our comprehension still

remaining. Perhaps humans and machines live together as equals, like in Iain

Banks' Culture series.

At any rate, even if they do not look much like us, they are something in whose

history we played a role. They could look back to us as we look back to the

scientists and engineers who created our lavish way of life.

What would they say about the Singularity? For them, it was a revolution in

life, a historic step forward. Still, time and again they have encountered

similar events of seemingly cosmic significance.

Remember - they say - the first time we figured out how to access a higher

dimension? Remember when we hit 80% of lightspeed for the first time? Remember

when we confirmed the existence of other universes? Remember when we encountered

an older and more powerful civilization for the first time? (Boy were we lucky

it was just the Chi Deltans!) Remember when we figured out how to share parts of

brains and consciousness?

Keep Your Trousers On

Human history may stop with the Singularity, but if it does not then

technological singularities will also become relativized. Our descendants, or

the successors to homo sapiens sapiens, will place existential progress into the

context of a historical process.

As Silicon Valley debates how and whether to approach the goal of a fully

general artificial intelligence, there is no reason to fall into the trap of

ceasing to think about what comes after the Singularity. The name itself, of

course, implies that there is nothing of importance after the Singularity (where

do you go after you enter a black hole? Certainly not home for tea!).

Just as relativizing scientific revolutions can help us approach them and think

about their implications and aftermath more intelligently, relativizing the

technological singularity could help us approach the matter in a sensible

manner.

Putting an existential occurrence into context can help us think a little better

about how to approach the design of AGI. And while I'm certainly not suggesting

we can forecast with any certainty what comes after the Singularity, I do think

we should keep in mind that there may be an after, and we should start thinking

about it in sensible ways as soon as we can, as soon as it makes sense to.