The Red Strings Club

Developer: Deconstructeam

Platform: PC

Genre: Adventure

Price: $14.99 USD

Buy on Steam

Warning: Spoilers

My first exposure to cyberpunk was Keanu Reeves yelling impotently into the sky that he wanted room service, a club sandwich and the cold Mexican beer.

Also a $10,000 per night hooker.

I learned shortly afterward that Johnny Mnemonic was originally a short story from William Gibson’s short story collection Burning Chrome, which I picked up shortly afterward.

The movie and the short story were… not very similar, but the short story had one character that could never be properly portrayed on screen: Molly Millions. A mercenary with wired reflexes and mirror sunglasses permanently adhered to her skull. The most common question that was asked in the series was a simple one: What color are her eyes? William Gibson knows the answer, and smirks when he says he’ll take the answer to his grave.

I read Neuromancer, the Idoru sequence, and Pattern Recognition afterward, and dragged myself through Snow Crash mostly to shut up my friends online. Cyberpunk played with metaphysics and transhumanism, and often would involve lengthy, talky sections where characters pontificated on the nature of existence, humanity, and morality. Sapience and sentience were always the watchwords, ways to further examine the facets of psychology and sociology, a “social science fiction”, if you will.

Cyberpunk is like that, actually, like being tricked into sitting through a college Ethics 101 lecture or in a car on a long drive with someone who’s stoned, a philosophy major, or both. It’s not to say you’ll think about some deep topics, but, like with cyberpunk, they’re like a vacation high, something that you enjoy in the moment, but move on from afterward. Cyberpunk obviously popularized neologisms like “cyberspace” (for the brief time it was used), and everyone in an MMO uses “avatar” to describe their online presence.

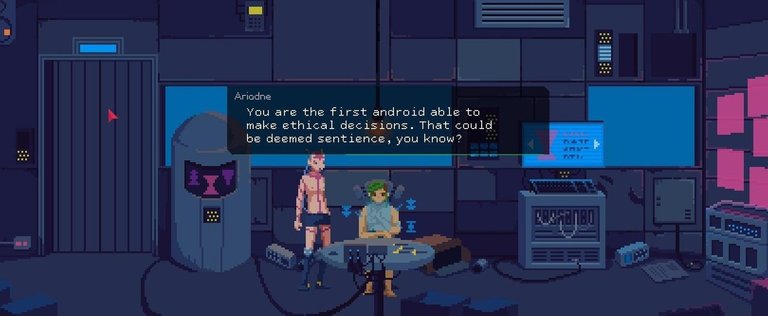

Cyberpunk, at its essence, is akin to an ethics thought experiment, and this is especially prevalent in Deconstructeam’s The Red Strings Club. A primarily text based adventure, the game centers around the titular Red Strings Club and its magical bartender, Donovan, as well as deuteragonist Brandeis, the true cyberpunk hacker type with the cable jack in his brain, mirror-shades, and anarchist tendencies. It’s essentially a melding of cyberpunk and urban fantasy, or, better put, Shadowrun without the orcs, elves or trolls.

Act I, generally the expository of a work, begins with establishing that AI is a thing, and that humanity is embracing implants that can make you more confident, uncaring of what society thinks of you, more persuasive, or if you really just want more Twitter followers. There are lasting consequences and difference choices to encourage multiple playthroughs as you proceed into Act II, where the meat of the game really comes to bear.

Let’s say you could control humanity. All of it. Not just yourself, or your friends, or your enemies. Everyone. Would you use that power responsibly? What if you could alter peoples’ emotions so that no one will ever be sad or angry? What if you could make it so that no one will ever be depressed, or suicidal? What if you could make it so that no one would ever be able to take a life, or take advantage of someone else? Would you do it?

Free will has always been an over-arching theme in cyberpunk, that no matter what kind of machinery we are putting in our bodies, if we are constructs of flesh and bone, or steel and code, sentience, sapience, and agency are that which is cardinal and sacred. Cyberpunk antagonists often detail arguments that humanity doesn’t want any of those things, but rather would prefer some force keep them in submission, making decisions for them whether they want it or not. They’ll then refer, cynically, to what humanity in the real world is already doing, how humanity is addicted to distraction, so why not give them what they want?

The Red Strings Club digs deep into this in Act II, where after you’ve questioned bar patrons, you have a philosophical quandary with an AI-driven android on the nature of macro-influences on society, what’s ethical and what’s not. Essentially, the patrons and the investigation are the distractions, the real game in is a short Q&A that determines the course of the rest of the game, the thread of fate that the game will let you check at any time, look at the notes you’ve been diligently keeping as you uncover corporate plots and unmask antagonists and make witty repartee.

Act III is where you reveal the game you’ve bought. There’s social engineering and making calls on a landline, but the challenge is gone. It’s simply a matter of trial and error and attempting to push the finale further into checkmate. The necessary final piece? A password, which is the former name, or deadname, of a trans woman character you meet in Act II. In order to save the world, you have a deadname a transgender woman. (To deadname a trans person is to call them by the name they used prior to their transition, and it's a really shitty thing to do. Seriously. Don't do it.) Y'know, bigger picture and all, but still, it's kind of a shitty thing for the game to make you do, but that's what all of those thought experiments in the second act are possibly for. It moves on quickly, and then there’s the exultant, but brief celebration of “Yay! We Won!” as the two male lovers breathe a sigh of relief that the world will remain unfucked for another day.

But that’s not the game you bought.

Nothing you did mattered. The game is perfectly happy to tell you this. The antagonist? Just a girl that might have threatened the real villain. The global threat on free will? Oh, that battle was lost since 2009, and everything you’ve done was perfectly according to plan. The one wrinkle is Donovan, and it’s not until you’re falling off a skyscraper to your doom that you have a few seconds to relay vital information, so that your death won’t be in vain.

But that’s not the game you bought.

Here’s another thought experiment: You’re 3 seconds from death and your lover is on the phone with you. You can say “I love you,” or tell them the identity of your killer, who is standing right next to them.

What would you do?

Your answer doesn’t matter. Donovan will drink a lethal shot of Plot Device Liquor, the game will close back to desktop, and your save log will be utterly deleted.

Despite your careful investigation, despite your heroics, despite the “choices matter” tags, despite the deep ethical conversations, the game was already decided in a macro sense from the word go. Everything else in The Red Strings Club is rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. There is no perfect solution, no walkthrough that will prevent the apocalypse. You’ll play, you’ll lose, and you will be forgotten.

It’s fatalistic. Nihilistic. And it executes plot devices rather than telling a complete story. But it has a decent soundtrack and some noir-ish dialogue.

So, it’s cyberpunk.

Cyberpunk Works to Read INSTEAD of Playing The Red Strings Club

Neuromancer – William Gibson

Snow Crash – Neal Stephenson

The Stars My Destination – Alfred Bester

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – Phillip K. Dick

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology – ed. by Bruce Sterling

Ghost in the Shell – Masamune Shirow

Altered Carbon – Richard K. Morgan

Trouble and Her Friends – Melissa Scott

Games to Play INSTEAD of The Red Strings Club

Deus Ex: Human Revolution

Shadowrun: Dragonfall

Shadowrun: Hong Kong

Hacknet

Uplink

Watch_Dogs 2

Would you put Ready Player One in the genre too? Or is that just too self-referential and overly steeped in popular culture?

RPO is so nostalgia drenched it's insulting. Learning that Wil Wheaton did the audiobook actually made me lose respect for him. There's nostalgia, and then there's the marketing of condescension.

I thought Ready Player One was a decent book (the movie looks terrible though). There is quite a bit of nostalgia but I'm not sure I see the link between nostalgia and condescension. I wouldn't want to listen to anything Wil Wheaton narrates. I saw him at a convention once and he really came across as a condescending asshole. All in the eye of the beholder I suppose.

It's more in the marketing, the expectation that you're going to like something simply because you get the references. The recent movie posters feel like seeing your parents trying to reference memes and thinking it makes them cool.

I guess that explains it. I saw the book at a bookstore a couple years ago and picked it up because it looked interesting. I never saw any marketing stuff until recently with the movie coming out. The movie doesn't look that good to me. I might watch it but it will be a rental.

I liked Snow Crash a lot. Much more than the William Gibson books I've read (thought to be fair I've only read Neuromancer and Burning Chrome). Snow Crash is not Neal Stephenson's best work though.

The Bridge Trilogy, or the Idoru sequence, is more about social media than cyberpunk hacking, and Pattern Recognition is about marketing and branding, trying to elicit what makes us see something as "cool". I've tried to get through Cryptonomicon, but at the end of the day I'm more of an urban fantasy guy than a cyberpunk guy.

I've been meaning to read more William Gibson but just haven't gotten around to it.

Neal Stephenson doesn't really write in one particular genre and Snow Crash (and maybe The Diamond Age) is really the only one I would describe with cyberpunk elements. I like Cryptonomicon a lot but I wouldn't call it cyberpunk. More like a modern day (for when it was written) technothriller mixed in with a little historical fiction and some cryptography. My favorite books of his were the three books of the Baroque cycle but they would best be described as historical fiction. You might like Reamde if you haven't read it. Another sort of modern day technothriller but dealing with online gaming and digital currency. Anathem and Seveneves were very good but more hard sci-fi.

Neal Stephenson has this thing that he does where he likes to dive into the technical details of stuff in his books, whether it be computers, cryptography, sword fighting, the monetary system or whatever. Some people really like this (like me) but others don't find it so appealing.

Mostly I'm more about characters than details. Like, in Snow Crash I wasn't a fan of Hiro and skipped ahead at points to the Y.T.'s sections as she was more interesting. In Gibson's works, Molly Millions was my favorite cyberpunk character (and still is), but I didn't much care about the others in the Sprawl trilogy. The others... It was working a late-night job and had time to read, so All Tomorrow's Parties and Pattern Recognition were more about killing time. :)

PR's look into "what makes something cool" was done better by Robert Pirsig in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance when he tried to pick apart the concept of "quality", in my opinion.

This post has received a 15.09 % upvote from @moneymatchgaming thanks to: @vaughndemont. Upvote this Post to Support the MMG Community on Steemit! :)

Will this get resteemed, as it's a gaming post?