One of the best known stories about Mohandas Gandhi takes place in a first-class train car upon his arrival in South Africa. A dramatization of it appears at the beginning of the 1982 film Gandhi. The viewer sees young Gandhi belittled for the color of his skin and then physically thrown off the train when he refuses to move to third class.

After this experience, Gandhi found himself in sitting in an unheated station that winter night, declining to ask for his overcoat and luggage in case he “should be insulted again.” The next morning, he was able to continue on his way, eventually arriving at his destination after additional hardships.

In Gandhi Before India, biographer Ramachandra Guha minimized the importance of the incident, pointing out that he “suffered no physical harm. He soon proceeded on his journey.” But physical abuse wasn't the significance of this interaction any more than when Rosa Parks refused to yield her bus seat 60 years later in Montgomery, AL. It was the moral rejection of the immoral status quo combined with a willingness to accept punishment that could have been easily avoided.

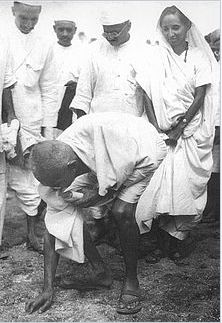

Gandhi's response to the threat of being forced off the train was simple and precise. “Yes, you may,” he acknowledged. “I refuse to get out voluntarily.” By accepting the use of force against him, Gandhi seized the moral high ground, even if there were no witnesses. He learned from the experience. Decades later, he made sure the whole world watched as he made salt.

Although his arrival in South Africa marked the third continent on which Mohandas Gandhi set foot, it was really his introduction to institutionalized racism. In his writings, he made no mention of discrimination as a young man in London; the vegetarians in his circle of friends had welcomed his foreign perspective. The white majority had treated him as an equal.

Things had gone badly almost as soon as he set foot in South Africa. On his second morning in his new home, he was startled to read in The Natal Mercury a description of his attendance at the magistrates' court with the headline “An Unwelcome Visitor.” When Gandhi made his first public appearance as the country's first Indian lawyer, the magistrate asked him to remove his turban. Rather than argue about it, Gandhi left the courtroom. How embarrassing that must have been for the young man, to find himself singled out like that! He waited outside for his client, Dada Abdulla, and wondered why there had been no objection to the Muslim's turban. After reading the newspaper article, he wrote to clarify his position – wearing a head covering was a sign of respect – and then climbed aboard the train to Pretoria.

Gandhi surely replayed the incident mentally and wished that he'd produced a proper rebuttal to the magistrate. With these thoughts spinning in his head, it could almost be seen as the hand of providence when he had a second opportunity to stand his ground. Take his first-class ticket back to third class? Absolutely not! Gandhi refused, this time delivering a forceful response to abusive authority. “Yes, you may. I refuse to get off voluntarily.”

There are two kinds of civil disobedience. The first is the kind Gandhi displayed with the Salt March. He announced a public flouting of the law and challenged the British to arrest him. It is courageous to voluntarily invite a penalty when one has done no wrong. But the civil disobedience itself is voluntary, done at a time and place of the activist's choosing. In that sense, the activist is a willing participant.

The second kind involves an unwilling participant and unplanned activism. Authority randomly rears its head, demanding submission, expecting compliance. The threat of a penalty is real and immediate. Caught off guard at the expected decision, many will acquiesce to an unjust demand; the tyrant expects it. Civil disobedience at a time and place of another's choosing is difficult.

Yet Gandhi met this challenge. He was surely afraid, on a train in a foreign country, but he acted with courage. “Yes, you may. I refuse to get off voluntarily.” Gandhi's first act of civil disobedience shows the strength of his character.

Sources:

Gandhi Before India (Guha, 2014)

An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth (Gandhi, 1927)

An earlier version of this article was published in two parts (1/28 & 1/29/18) on Reddit as part of the 30-day Gandhi challenge, where participants abstain from alcohol for 30 days (Gandhi didn't drink) and fast for 24 hours. (Gandhi fasted for as many as 21 days.)