Source Image: Wikimedia by Wheller007

Good day everyone, welcome to my first post on this topic that i will be sharing with you, enjoy!

Water is the most important factor sculpturing the earth’s surface. Mountains rose by the activities of plate tectonics and volcanism, but are molded primarily by water. Streams valleys, level plains, move enormous weight of sediment from place to place. Floods are presumably the most widely experienced catastrophic geologic hazards. On the average, in the United States alone, floods annually take over eighty-five lives and cause well over $1 billion in property damage. Most of these floods do not make national headlines, but they are no less devastating to those affected by them. Some floods are the result of unusual events, such as the collapse of a dam, but the vast majority are a perfectly normal, and to some extent predictable, part of the natural functioning of streams. Before discussing flood hazards, therefore, we will examine how water gives through the hydrologic cycle and also look at the basic characteristics and behavior of streams.

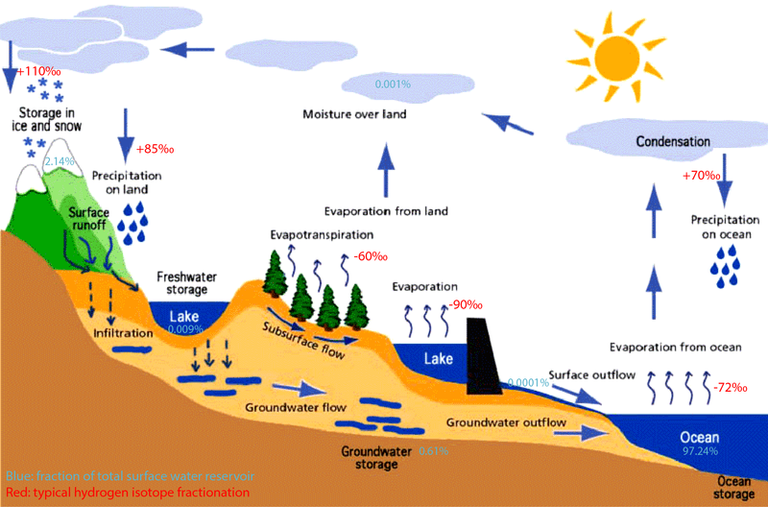

THE HYDROLOGIC CYCLE

The hydrosphere contains the water at near the surface of the earth. Most of it is believed to have been outgassed from the earth’s interior early in its history, when the earth’s temperature was higher, except for periodic minor additions from volcanoes bringing up ‘’new’’ water from the mantle, the amount of water in the hydrosphere remains essentially constant.

Source Image: Wikimedia by Sunson08

All the water in the hydrosphere is taken up by the hydrologic cycle. The biggest single reservoir in the hydrologic cycle includes the world’s oceans, which contain 97.5 percent of the water in the hydrologic; lakes and streams that contain only 0.016 percent of the water. The main procedure of the hydrologic style includes evaporation into and precipitation out of the atmosphere. Precipitation onto land can re-evaporate. Invade into the ground, or run off over the ground surface. Surface runoff may occur in streams or by unchanneled overland flow. Water that sinks into the ground may also flow and commonly returns, in time, to the oceans.

The oceans are the principal source of evaporated water because of their vast areas of exposed water surface. This total amount of water moving through the hydrologic cycle is large, more than 100million billion gallons per year.

A portion of this water is temporarily diverted for human use, but it ultimately makes its way back into the natural global water cycle by a variety of routes, including release of municipal sewage, evaporation from irrigated fields, or discharge of industrial waste-water into streams.Water in the hydrosphere may spend extended periods of time-even tens of thousands of years-in storage in one or another of the water reservoirs, but from the longer perspective for geologic history, it is still regarded as moving continually through the hydrologic cycle.

STREAMS AND THEIR FEATURES

Streams-General

A stream of flowing water confined within a channel, regardless of size. Flowing downhill through local topographic lows, carrying away water over the earth’s surface. The zone from which a stream draws water is its drainage basin. The size of a stream at any point is interconnected in part to the size (area) of the drainage basin upstream from that point, which regulate how much water from falling snow or rain can flow into the stream. Its size is also influenced by several other factors, including climate (amount of precipitation and evaporation), vegetation or lack of it, and the underlying geology, all of which are explained in more detail later in this topic, length of time. Discharge is the products of channel cross section (area) times stream velocity, historically, the mainstream unit used to show discharge is cubic feet per second; the analogous metric unit is cubic meters per second. Discharge varies from less than one cubic foot per second on small creek to millions of cubic feet per second in a paramount river.

Sediment transport

Water is a powerful factor for moving material. Streams can move material in several ways. Heavier debris may be rolled or pushed along the bottom of the streambed. This material is then described as the bed load of the stream. The suspended load consists of material that is light or fine enough to be moved along suspended in the stream, supported by the flowing water. Suspend sediment clouds a stream and gives the water a muddy appearance. Material of intermediary size may be carried in short hops with the streambed by a process called

Source Image: Wikimedia

saltation. Some substances will be completely dissolved in the water, to make up the stream’s dissolved load. The amount of material that a stream conveys these methods is called its load. Stream volume is measured by the total load of material a stream can move. Volume is related to discharge: faster the water flows, and more the water is present, the more material can be moved. How much of a load is actually transported also depends on the availability of sediments or solutable material: A stream flowing over solid bedrock will not be able to dislodge much material, while similar stream flowing through sand or soil may move considerable material.

Velocity, Gradient, and Base Level

Stream velocity is related partly to discharge and partly to the steepness (pitch or angle) of the slope down which the stream flows. The steepness channel is called its gradient. All else being equal, the higher the gradient, the steeper the channel (by definition), and the faster the stream flows. Gradient and velocity commonly vary along the length of a stream, especially if the stream is a large one. Nearer its source, where the first perceptible trickle of water signals the stream’s existence, the gradient is usually steeper, and it tends to decrease downstream. Velocity may or may not decrease correspondingly: The effect of decreasing gradient may be counteracted by other factors, including increased water volume as additional tributaries enter the stream, and changes in the channel’s width and depth. By the time the stream reaches its end, which is usually, flows into another body of water, For most streams, base level is the water (surface) level of the body of water into which they flow. For streams flowing into the ocean, for instance, base level is sea level. The closer a stream is to its base level, the lower the stream’s gradient. It may flow more slowly in consequence, although the slowing effect of decreased gradient may be compensated by an increase in discharge. The downward pull of gravity causes a stream to cut down toward its base level. Counteracting this erosion is the influx of fresh sediment into the stream form the drainage basin. Over time, natural streams tend toward a balance, or equilibrium, between erosion, and deposition of sediments. The longitudinal profile of such a stream (a sketch of the stream’s elevation from source to mouth) assumed a characteristic concave-upward shape.Velocity and sediment sorting

Variations in a stream’s velocity through its length are shown sediments deposited at various points. The term competence is used to describe the largest particles; it can be moved under a given set of stream conditions (velocity and flow dynamics). The sediments found motionless in a streambed at any point are those too big or heavy for that stream to move to that point. Where the stream flows quickly, it carries gravel and even boulders along with the finer sediments. As the stream slows down, it starts dropping the heavies, largest particles-the boulders and gravel-and continues to move the lighter, finer materials along. IF stream velocity continues to decrease, consecutive smaller particles are dropped: the sand-sized particles next, then the clay-sized ones. In a very slowly flowing stream, only the finest sediments and dissolved materials are still being carried.

The relationship between the velocity of water flow and the size of particles moved accounts for one characteristic of stream-deposited sediments: They are commonly well sorted by size or density, with materials deposited at a given point tending to be similar in size or weight.

If a stream is still carrying a substantial load s it reaches its mouth, and it then flows into still water, a large fan-shaped pile of sediment, a delta, may be built up. A similarly shaped feature, an alluvial fan, is formed when a tributary stream flows into a more slowly flowing, larger stream, or a stream flows from mountains into a dry plain or desert. An additional factor controlling the particle size of stream sediments is physical breakup and/or dissolution of the sediments during transport. That is, the farther the sediments travel, the longer they are subjected to collision and solution, and the finer they tend to become. Stream-transported sediments may thus tend, overall, to become finer downstream, whether or not the stream’s velocity changes along its length.

Floodplain Evolution

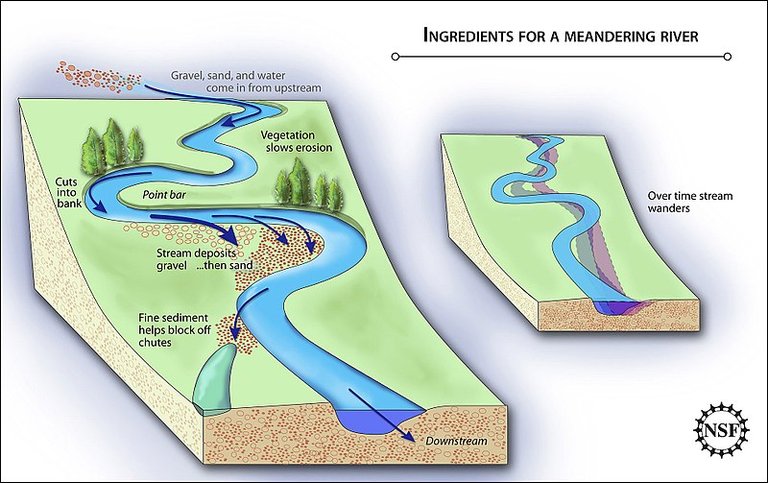

Streams do not ordinarily flow in straight lines for very long. Small irregularities in the channel cause local fluctuations in velocity, which result in a little erosion where the water flows strongly against the side of the channel and some deposition of sediment where it slows down a bit. Beds, or meander, thus begin to form in the stream, once a meander forms, it tends to enlarge and also to shift downstream.

Source Image: Wikimedia

The rates of lateral movement of meanders can range up to tens or even hundreds of meters per year, although rates below 10 meters/year (35 feet/year) are more common on smaller streams.

Over a period of time, the effects of erosion on the outside banks and deposition inside banks of meanders, and downstream migration of meanders, produce a broad, fairly flat expanse of land with sediment around the stream channel proper.

This is the stream’s floodplain, which is the area into which the stream spills over during floods. Sediment deposition during floods can be an important extra element contributing to the formation for this flat tract surrounding the channel. The floodplain, then, is a normal product of stream evolution over time. Meanders do not broaden or enlarge indefinitely.

Source Image: Wikimedia

Very large meanders represent major detours for the flowing stream. At times of higher discharge, especially during floods, the stream may make a shortcut, or cut off a meander, abandoning the old, twisted channel for a more direct downstream route. The cutoff meanders are called oxbows. These abandoned channels may be left dry, or they may be filled with standing water, making oxbow lakes.

Thanks for reading

References list:

- Streams and Drainage Systems

- Streams and Flooding

- Stream Types

- Britannica.com: Flood

- Water basics: the hydrologic cycle

- Sediment Transport and Deposition: Environmental measurements

Further Reading:

- Hughes, Richard, "The Effects of Flooding upon Buildings in Developing Countries", Disasters, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 183-194, 1982.

- Schware, Robert, "Official and Folk Flood Warning Systems: An Assessment", Environmental Management, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 209-216, 1982.

- Brown, Richard; Chanson, Hubert; McIntosh, Dave; Madhani, Jay (2011). "Turbulent Velocity and Suspended Sediment Concentration Measurements in an Urban Environment of the Brisbane River Flood Plain at Gardens Point on 12–13 January 2011". Hydraulic Model Report No. CH83/11. Brisbane, Australia: The University of Queensland, School of Civil Engineering (CH83/11): 120. ISBN 978-1-74272-027-2.

- Bortleson, G.C., and D.A. Davis. 1997. Pesticides in selected small streams in the Puget Sound Basin 1987-1995. USGS Fact Sheet 067-97.

You received a 10.0% upvote since you are not yet a member of geopolis and wrote in the category of "geology".

To read more about us and what we do, click here.

https://steemit.com/geopolis/@geopolis/geopolis-the-community-for-global-sciences-update-4

Congratulations @moabdul123! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP