I saw two buses in the Port-au-Prince bus station, one small and one large. The Haitian man who had guided me around his country said I should take the smaller bus, known in Haiti as a “Tap Tap.” In front of me was the less colorfully decorated Dominican version, known as “Guaguas.” I stepped onto the bus for a peek. It was almost full and I knew the other bus would have more comfortable seats and a smoother ride. A man outside organizing the bus seating insisted I get on and pushed down a seat for me in the middle behind the driver seat. As soon as I sat down, the driver, a Dominican, started yelling at me, telling me he had his stuff in my seat. Others behind me were yelling too. It was early, and I didn’t have the energy to argue. I stepped off the bus and told my Haitian guide that I wanted to take the other bus. He tried to get his money back from an obese woman sitting in a chair, but she said he could not. He tried to grab it and she pulled it away. She was the fattest woman I had ever seen in the Caribbean. Everyone was standing while she sat in a chair counting money. Many Haitians loitered around the buses. There wasn’t much room and I didn’t want to lose my chance to leave Port-au-Prince. I had given away all my possessions other than my camera equipment and clothes I wore. I had given my guide my sneakers and wore socks and flip flops. The coolness from the night still lingered in the air, but I knew the bright sun and another 100-degree day was just hours away. Knowing this, I looked at the smaller bus and asked my guide the first thought that popped into my head, “When does this bus leave?” He spoke in Creole to the man who had urged me to get on, and said the bus leaves at 8, and that it was the first to leave. It was almost 8.

“You don’t have any choice,” said my guide.

Again, I sat in the same seat near the front. People got in and out. With my big, black camera backpack on my lap I was crammed between two other passengers. It’s only seven hours, I thought to myself, I can endure it and then I’ll be in Santo Domingo. I wanted to go home. My supply of Clif Bars was down to two in my pocket. I had only washed myself once during my week-long visit, and I didn’t brush my teeth that often. I had worn the same shirt and underwear almost every day. Though, physically, I felt good. Mentally, the devastation had taken its toll. I felt helpless. Whatever good I had done really didn’t amount to anything. The Haitians were running on a treadmill, and now I was leaving. More than any other time in my life, I felt lucky to be an American. I was not, however, home just yet….

As the bus pulled out of the terminal, I waved to my guide who had waited to make sure I left ok. He gave me a thumb’s up. I wished he was on the bus with me to quiet a young Haitian girl who wouldn’t stop crying. She became hysterical and the driver stopped the bus just a few blocks outside the terminal. He walked over to the other side of the bus and opened the door. He spoke Spanish to the girl, and a young Haitian man behind me translated it into Creole. It didn’t work. Then a Dominican woman lifted the child into her arms and tried whispering and stroking the girl’s head. That didn’t work either. Someone passed some crackers to the front along with a juice pack. The girl drank the juice and ate a cracker while crying and complaining at a lower tone. The driver returned to his seat and the bus took off.

The bus had 28 passengers, including myself. Then there was the Dominican driver and the two Dominican women. Everyone else was Haitian. Behind me a Haitian man asked me in Spanish if I spoke the language. I told him I did not speak Spanish. This was a lie, but I was tired and just wanted to rest. He asked me if I liked Jesus. I told him I did. I thought this would quiet him. He was the only Haitian who spoke Spanish. None of the Dominicans spoke Creole. The few Haitians that spoke English were returning to their homes in the United States just like me. The Spanish-speaking Haitian man then stood up and faced the back of the bus and began reciting a Christian prayer in Spanish. Unlike most Americans, Dominicans and Haitians are not hesitant to express their religious beliefs to strangers. This was not the Lord’s Prayer. It seemed to never end. I just wanted some quiet so I could get some rest. Having spent a month in the Dominican Republic, I knew this was not possible with Dominicans aboard. Little did I know how right I was….

The young Haitian girl cried less and less. Looking out the windows I could see Haitian women carrying large jugs of water and other heavy items on their heads. Large tractor trailer trucks filled with water and supplies drove toward Port-au-Prince. The air was growing hotter as the dust on the ground mixed with the pollution from the congested roads. Now, more than two weeks later, it had not rained since the earthquake. We waited in traffic and after a very long morning we approached the border, where the paved road turned to dirt. To our right were steep, barren hills. To our left I saw a Haitian boy standing under a tree with no leaves, fishing into the lake. The boy was using a tree branch for a fishing pole and wore tattered clothes.

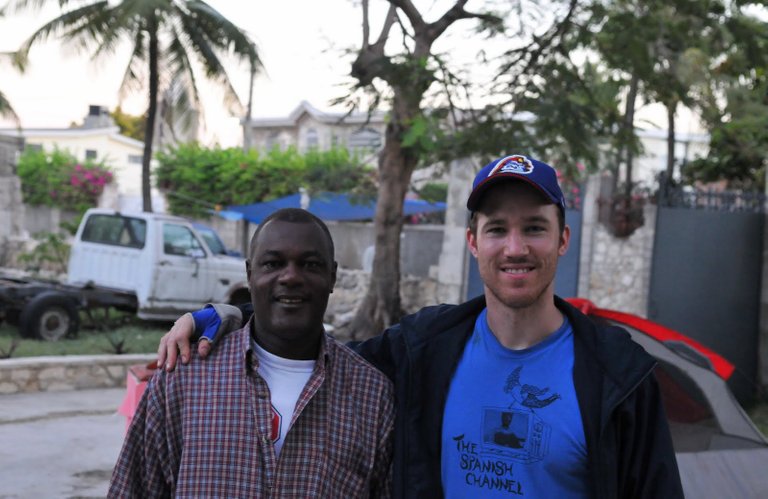

Dominican soldiers opened the gate for us to cross the border. I figured the worst was behind me. Although it was almost noon, the rest of the ride would be smooth sailing. We passed the military compound where missionaries and journalists resided before they crossed. The road was dirt and had potholes, and rubble filled the gaps between the parked trucks packed with foreign aid. Our driver parked on the left side of the road and the skinnier Dominican woman told everyone they had to take out their passports. Across the street stood a small building, and inside it looked like a currency exchange office. There were three short lines. I had given the Dominican man my passport and he stamped it without saying a word. Behind me a young Haitian man asked me if I was a journalist. He spoke English with a Creole accent. I told him I was a photographer, not knowing his intentions. I had never seen him before, but he had a big smile as if he had known me for years. On the bus we began to talk. His name was Thoby and he split his time living in Orlando, Fla., and the Bronx, N.Y. He seemed to have a perpetual smile, even when he told me that 55 members of his family had died in the earthquake.

A little farther down the road the driver parked the bus. The sun was high in the blue sky and beat down on the dry earth. Outside the bus, vendors sold drinks and snacks. I did not want to leave the bus and have my seat taken. I was thirsty, but I didn’t want to drink my water bottles because I would have to go to the bathroom, and again, possibly have a worse seat. I could not leave my large camera bag out of my possession. It had a week’s worth of video and photos taken in a country with no electricity. I had slept in a tent the entire trip and had taken just one bath. I was not about to lose it. Maybe I was paranoid. I do not think so. I was in an area where people were desperate for money and a better life. I didn’t want to take any chances. After a few minutes the Dominican woman who held the Haitian girl said everyone had to leave the bus. We had to visit customs. It looked like a rest stop. The small brick building had one open room and a couple small rooms behind closed doors and windows.

Everyone seemed confused. Didn’t we already get our passports stamped at the last stop? As I entered the make-shift customs building, a group of young Dominican men stood in a circle arguing. People, mostly Dominicans, were standing everywhere. I was the only white person. There was no air-conditioning, and it was probably 90 degrees inside the room. There was one window where some people were waiting near the far left corner. A Dominican policeman told us we had to wait in line, so we did. There were just a few people ahead of us. The line didn’t move because people kept coming up to the front and talking to the customs agents behind the window. I held a heavy bag for a Haitian woman standing next to me in line. She was going to visit her husband in Connecticut. I saw sweat drip down her face as she smiled and thanked me. Then the skinner Dominican woman from the bus came in and told us to give her our passports. She already had a handful of Haitian passports. We gave her our passports and she walked through a door into the room with the customs agents. She looked like she knew what she was doing. Maybe the Dominican buses had a deal with the customs agents to expedite the process. Still, I wasn’t sure whether to wait in line. I decided to not take any chances and kept my spot. The Haitians next to me did the same. I had not seen Thoby. I didn’t understand why we had to stop at customs again. I began to sweat as my camera bag and the bag I was holding felt heavier. By the time we made it to the custom’s agent at the window, the Dominican woman was talking to him on our behalf. The other agents sat around the room doing nothing. It was past noon by now. Finally, the Dominican woman emerged with our passports. We could get on the bus. Outside, the sun felt the same as it had in Haiti, which rose above 90 degrees. Thoby greeted me and asked if I wanted food or a drink. I told him no thanks. He insisted and handed me some crackers. We boarded the bus, and I sat in the same seat. Sweat dripped down the faces and chests of the other passengers. I still did not want to drink my water bottles just yet....

We had not gone far when the driver stopped the bus. It was a security checkpoint. A soldier stepped onto the bus and asked everyone for his or her passport. When he asked me, I told him I was American and that I had no reason to show my passport. It made no sense. Why did we have to show our passports three times? I obviously was not a Haitian crossing the border. I refused to show it to him and he relented.

We passed another security checkpoint and the soldiers waved us through without stopping as the packed bus continued down the desolate road. By now, it had been more than five hours since we left Port-au-Prince. Then I heard a noise from the rear. The road was on a straight-away with no other vehicles in sight. The driver pulled over. A wheeled storage unit was connected to the back of the bus and filled with luggage. It had a flat tire. I thought, what else could go wrong? It was a beautiful day with a bright sun and white clouds in the sky. There were palm trees and mountains in the distance. Down the road it looked like freedom. Yet I was reliant on this bus since very few drove this far west of Santo Domingo. The Haitians stood in the shade under the trees and thicket that grew on the side of the road, next to cactus and bushes with prickers.

The driver used a large rock from the side of the road to jimmy the hitch while he removed the flat tire. He couldn’t remove a bolt to put on the spare tire. He had to wait until a motorcyclist drove by and he rode with him in the direction we had already traveled. We waited an hour until he returned with the necessary tools to replace the tire. No one seemed to care that we had been traveling for six hours and were still close to the border. The ride to Santo Domingo would be another six hours. At least this was what I thought at the time. I figured we were already late so they would feel conscientious about getting us there as fast as possible.

By this time I relented and began drinking one of my water bottles. I had planned to drink them at the airport. Just a few minutes down the road we came to another military checkpoint. This time an older soldier stepped onto the bus and said he wanted everyone to get out and show him our passports.

“How many times do you have to look at our passports?” I asked in Spanish as we boarded the bus. “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven…”

I kept counting and he continued, “Yes, eight, nine, ten … however many times is necessary.”

“This is crazy,” I replied. “It doesn’t make sense.”

I did not care if he was in the military. We had paid our money. We should be treated like tourists, not like criminals. We have done nothing wrong, I thought.

The driver drove just a few hundred yards down the road and suddenly swerved to the right and then turned to the left, putting the bus perpendicular to the road. There was a curve just ahead. The way he had jerked the wheel and stepped on the accelerator drew screams from the passengers, but he just laughed to himself. He reversed the bus, but it was too tight a squeeze. This guy is crazy, I thought. What is he trying to do? Not far ahead, he found a wider space and made a U-turn, and began driving back toward Haiti.

“What is going on?” I asked Thoby.

“I guess we have to go back to show our passports at that checkpoint. This is some bullshit.”

We went back to the checkpoint and got out of the bus and showed the soldier our passports. He talked on his phone with the soldier from the checkpoint ahead. Finally, he let us go.

I was tired, thirsty, and hungry, yet I was still optimistic that the worst was behind us, and that we’d make it to the airport in the evening.

This all happened before the bribes. We passed the checkpoint that had sent us in reverse and sure enough there was another checkpoint not too far past it. The checkpoints were set up about a mile or two apart from one another. We stepped off the bus and handed our passports over. I was upset but thought we would only have a couple more stops. When I had first arrived to the island, my Dominican friend had given me a ride late at night past all these checkpoints. At the time, most of the soldiers or people watching them were dozing off in chairs either on the side or in the middle of the road. There were no lights and my friend had almost made them jump from their chairs when he swerved past them at 50 miles per hour. There were only six or seven checkpoints. Things were different now. The soldier asked the fat Dominican woman how many people were on the bus. She said 28. He looked through the passports and discovered that some of the Haitian passengers were entering the Dominican Republic illegally. The fat woman pleaded with the soldier and told him she could give him money as she sat in a seat to herself. They bargained back and forth. She kept her money at the only accessible place: inside her bra. She handed him 300 Dominican pesos, about 10 U.S. dollars. He let us go.

This occurred several more times with the fat woman bribing her way to the next checkpoint. It was nearly dark when we stopped in a small town for food. We had been on the road for nearly 12 hours and had not eaten. Unfortunately, all that was open was a snack stand. I was too tired and upset to pretend I did not speak Spanish. I told the skinnier Dominican woman that I was angry, and that we had traveled all day, gotten nowhere, and had not eaten anything. She said we were going to eat soon, and acted like it was no big deal. I walked across the street where Thoby was buying an orange drink. He bought one for me and I said, “Maybe we should try and hitch a ride with someone to Santo Domingo.”

“You want to?” he asked.

I hesitated for a minute, thinking about what to do. Then we decided there were only a couple more checkpoints and since we already had paid our way there was no point in paying someone else for a ride. Thoby was now broke, but I told him I would front his ride. Nevertheless, we sauntered back to the bus where the fat woman was telling us to hurry up.

After a couple more checkpoints we stopped in another small town that had a small store that sold drinks and dinner, if you want to call it that. The passengers rushed to it like they had when aid arrived to their country. By the time I got to the stand there was just some overcooked fried chicken. No fried plantains. Nothing else. I bought two plates of dried meat for Thoby and me. As I walked to the bus, a soldier was checking passports and the fat woman was telling us to hurry up. I took one bite of the fried chicken and threw the rest out. Sometimes it is better to starve. I wiped my greasy fingers on my pants and boarded the bus.

At this point I did not care about politeness or respect authority. I wanted to be taken to the airport and I wanted my money back. We passed several more security checkpoints. I did not bother making a fuss or talking to anyone other than Thoby and another American-Haitian man from Miami. At one of the checkpoints a young soldier in street clothes checked our passports and said we could not go on. He said we had to turn around. He shook his head no when the fat woman tried bribing him, and said he had not received orders from any of the soldiers at previous checkpoints. He called another soldier and left a message. In the meantime we had to wait. What else was new? The fat woman pleaded with the young man but he wouldn’t give in. The young man seemed very serious about his job as a group of young soldiers in uniform sat on chairs along the side of the road observing him. The young man finally received a call. He told us we had to turn around and go back to one of the previous checkpoints. Thoby, the Miami man, and I told the driver and the Dominican women we refused to go back. We were talking about hitching a ride, but it was too far and too dark and dangerous. We had no choice. Yet we knew we could not go back. We had flights to catch and it was already dark outside. They talked among themselves and then the skinnier Dominican woman picked up the young Haitian girl who had cried hysterically at the trip’s outset. They walked to where the young soldiers and the other soldiers stood behind the bus. In their place, a tall, young Dominican woman sat in the back of the bus as we drove off. I was a bit confused as to what exactly happened, but I was glad to keep going forward. Besides, the two we left behind were annoying.

The farther we drove, the more dramatic the interaction between the soldier and the fat woman at each security checkpoint. She never stepped off the bus. Instead, she sat next to the door and looked as if she was going to cry as her forehead wrinkled up with a pained expression. She did not want to give her money away. That greedy bitch, I thought. Many of the soldiers taking the money stepped inside and closed the bus doors so the other soldiers couldn’t see them taking the money. They were all greedy bastards, I thought. What a corrupt country.

We must have gone through at least two dozen checkpoints, and stepped off the bus at most of them to show our passports. However many checkpoints there were, the fat woman could not bribe her way to Santo Domingo. She fumbled around her bra. She had run out of cash. By now it was obvious all the soldiers were in the know because they had communicated through cell phones or walkie-talkies. There were still more checkpoints ahead. Thoby and I were using many four-letter words as we talked about the situation. We waited longer than usual when at last a young Dominican soldier dressed in uniform stepped on the bus and sat directly in front of me. He held an M-16 rifle between his legs. The bus grew silent. Fear in the air was palpable. I did not trust any of these soldiers. I tried avoiding eye contact with him and looked out the bus windows as we drove into the night. I could faintly make out the terrain thanks to an almost full moon. We passed fields of wild grass and bushes that looked as if humans had never set foot on them. The mountains looked like a painting in the distance to our left. We came to a small city called Barahona. Bright, ornately decorated street lamps lined edges of the city’s center square. It was brighter than the other towns we had passed. It wasn’t, however, as bright as the baseball field. A few blocks away teenagers were playing a game. For a moment I forgot about my situation and felt happy inside as I gazed at ballplayers. Baseball was the primary reason why I had taken two previous trips to the island. That feeling quickly evaporated as the soldier ordered the bus driver to take the next left off the main road.

We turned onto a dirt road that abruptly stopped as we passed a row of palm trees that stood in an empty grass field near a two-story concrete building. The bus pulled to a stop in front of the building. Everyone on the bus was still silent. The soldier stepped off the bus and greeted two men in street clothes. They had walked out of the building and both men looked like they were in their 30s. One of the men was wearing a tight, white sleeveless undershirt and had a goatee. They began talking, but I couldn’t hear what they were saying. Everyone on the bus sat in silence. Another man walked out and talked with the two men and the soldier. After a few minutes, one of the men stepped on the bus and asked the fat Dominican women how many illegal people were present. She said there were four, pointing to four Haitians in the back. She pleaded with him, but he ordered her to step off the bus. The men helped her stand up and get off. They put a folding chair on the grass facing the bus. She sat on the chair and tried persuading the men. She had that same pained expression on her face as the man with the goatee shook his head and said, “This is not good. This is not good.” The other men said a few things to her and she stopped talking. Then one of the men stepped on the bus and ordered us to give him our passports.

“What’s going on?” I asked Thoby.

“I don’t know, but be very careful with your stuff. I don’t trust any of these guys,” he said.

I had been holding my professional still camera, and asked Thoby to store it in his empty bag, which he gladly did. I didn’t want them to know I was a journalist and carried expensive equipment. Thoby and I whispered to one another. The man with the passports walked behind the bus and back into the building.

We waited and waited. Finally he returned, and gave us our passports. I couldn’t take sitting in that crammed bus and stepped off. Thoby did the same and then a few others. We stood near the fat woman, and talked in quiet voices.

“They can do whatever they want with us,” Thoby said.

“I know. If anything happens, I am going to run over there,” I said, gesturing toward the bright lights of the baseball field in the distance across the main road.

We waited for about a half hour and then I said to Thoby, “Maybe we should make a run for it over there. It’s dark, they won’t be able to see us and we can hide in those bushes until morning and then hitchhike back to the capital.”

“It is too dangerous. We don’t know anyone around here. They can rob us and then we will be fucked.”

One, bright light at the top corner of the building’s roof cast an eerie green glow exposing the pieces of chipped paint on the side of the building’s wall. The anger I had earlier subsided and now I felt nervous.

Just then the man with the goatee brought out a young soldier dressed in uniform, carrying an M-16 rifle, and ordered him to stand and watch us.

“Do not let anyone go beyond this point,” he said.

Saying the soldier looked 18 was a stretch. He stood at attention and said nothing. He looked like he was trying to hide his nervousness.

Are they going to line us up and shoot? Are they going to steal our stuff and cover it up? Thoughts popped into my head. I could see the look of fear on the Haitian faces through the bus windows. We waited for what seemed like an eternity. It was past 11 p.m. Thoby motioned for me to follow him. We walked to the other side of the bus where the driver was sleeping on the ground right next to the building. I noticed the tall, young Dominican woman talking with the fat woman and the other men from inside the building. Thoby told me she must be working for the police because she spoke Creole and Spanish. I thought he was being paranoid until I heard her speak both languages on her cell phone. She was dressed in street clothes as well.

I turned on my cell phone. It had one bar of battery life. I called my friend Denny, who had lived in Santiago and had driven me to the Haitian border a week earlier. He answered his phone. I cut to the chase and explained the situation. Denny said he would make some calls and see if he could find a person in Barahona to give me a ride. As I waited, the tall Dominican woman started flirting with me. I didn’t trust her, but shot the breeze anyhow. Denny called me back and told me that he couldn’t find anyone. I understood. It was a week night, and Santiago is about five hours from Barahona.

I had to just wait. A man wearing a short-sleeve, collared shirt, jeans, and shoes arrived. His close looked like they had just been laundered and he had just been to the barber. He was about my height and whiter than most Dominicans and looked like he was in his early 30s. He seemed to show up out of nowhere. He walked slowly with a grin on his face that said, it feels good being the boss. He asked the other men certain questions and they answered only when questioned. He and the tall Dominican woman laughed together like long-time friends. I got the nerve to talk to him. I walked closer and told him in Spanish, “Some of us have done nothing wrong and need to catch our plane flights early in the morning.”

The other men were still huddled around him, but he turned to me and asked, “How many?”

“There are four or…”

Just then some other Haitian Americans began raising their hands. The Haitian from Miami said there are six and I repeated, “Six.”

“What are you doing here?” he asked me with a grin.

“I was visiting Haiti, trying to help the people.”

“You are from America?”

“Yes.”

“What city?”

“I live in New York.”

The Haitians could not understand our conversation. I walked closer.

“Are you the general?” I asked.

“No, I work for the secret service,” he said.

“Where is the general?”

“He is sleeping.”

“So you guys don’t want to wake him up?”

“For terrorism or something like that we call the general, but for something like this they call me.”

He had that same grin on his face, and joked around with the girl. If we were at a bar I probably would have bought him a drink, but I was apprehensive. I slowly walked away as he talked with the tall Dominican woman. Then he asked to see the passports of the illegal Haitians. He also asked for them to stand outside the bus in front of him. They had been inside the bus the whole time. They stepped off and stood in a line. There were eight of them, five adults and three children. He looked carefully at each of their passports and the tall Dominican woman translated for him between Creole and Spanish. They stood their silent in the eerie green light. It looked as if they were facing the verdict for a murder trial. The fear was most prominent in the eyes of a young girl. The boss pointed to a tall 20-year-old Haitian woman at the end of the line near us and to a middle-aged Haitian man. He said he could let the others across, but he couldn’t let her and the man go. The tall Haitian woman began crying and begged him to let her go see her dying cousin in a Santo Domingo hospital. He shook his head as tears rolled down her face.

“Why don’t you marry him?” the boss said moments later, gesturing toward me and smiling. He then began to talk as if he was conducting a news conference.

“You see, the situation right now is, there are too many Haitians in the capital. They are intelligent, but they are poor….”

We continued to wait. I looked at my phone. It was a quarter until midnight. I told Thoby that I was not going to wait until after midnight to leave. I picked up the phone and called Denny. He didn’t answer. I tried a couple more times. No answer. I felt desperate. I called my brother. I was going to have him call Denny for me because I thought my phone was about to die. My brother answered the phone.

“Do you have a paper and pen?”

“Yeah.”

Just then Denny called me.

“I have to go. I’ll talk to you soon,” I told my brother and hung up.

Denny asked me what was going on. I told him I didn’t know what was happening and that we had a lot of illegal Haitians on the bus and that the secret service was here. I told him I didn’t trust anyone. Since he spoke fluent English and Spanish, I put him on the phone with the tall Dominican woman. They talked for less than a minute and she handed the phone back to me.

“Don’t worry. She said you’re leaving right now,” said Denny.

“Are you sure?” I asked.

“That’s what she said.”

“Hold on. Don’t get off the phone until I know for sure.”

Then Dominican woman motioned for us to get back on the bus.

“Are we going?” I asked her.

“Yes.”

“I guess we are going. Thank you for your help,” I told Denny.

“No problem. Call me if you need anything. I’ll come and get you.”

“Ok. Thank you. I’ll give you a call tomorrow.”

We boarded the bus and two of the men in the building got on with us. One sat next to the driver. The other stood next to the door, next to me. They wore street clothes.

We still had a long way to go….

The driver broke the silence as he chatted to the man next to him, who faced us. No more than ten minutes later, the man next to me got off at the next town. Of course the trend continued: when someone got off, someone got on. That someone was the Dominican woman and the crying Haitian girl from earlier. Where they were and how they caught up to us I do not now. By now the girl was tired and quiet, thankfully. Just a few miles down the road we stopped at a gas station. I stepped off the bus to stretch my legs and try and get fresh air. Two Haitian women stood next to me near the bus and lifted their legs to pee. I felt nauseous. Thoby told me he had to shit, and went to look for the gas station bathroom. I was glad I had not eaten much of anything.

Thoby was the last one on the bus as we drove down the dark road. I noticed him start to fall asleep. I also noticed the driver going faster than before. The bus was quiet. As he began driving downhill and around a curve to the left, I saw lights coming from the opposite direction. The driver didn’t slow down. He was easily going 50 miles per hour. As he rounded the curve, I saw two freight trucks ahead: one in the right-hand lane, and the other trying to pass it. The driver didn’t slow down. We were headed right toward the truck. I thought I was going to die. It all happened in a few seconds, but it felt like it was in slow motion. The driver swerved to the right at the last possible second. The bus shook side to side as we drove off the road right next to a steep, hill. If the bus wasn’t so jammed packed we would have literally tipped over and rolled down the hill. The Haitians onboard screamed as it was happening. I was in too much shock to scream much as I could feel my heart pumping fast. When the bus stopped, a young Haitian woman sitting next to Thoby began breathing heavy. I saw her chest go in and out as she puffed her inhaler.

“What is wrong with her?” I asked Thoby.

“Her inhaler is empty. I think she is having an asthma attack,” he said. Everyone was looking at her but no one was doing anything.

I had an EpiPen in my bag because I am allergic to bees. It is an auto-injection device that helps people with allergic reactions until they reach a hospital. I had never used it before.

“I have an EpiPen. It will give her a shot of adrenaline. Ask her if she wants it,” I said to Thoby.

He asked her and she said she wasn’t sure. She was breathing heavy for air as her chest expanded and went down. She kept using her inhaler but it had no spray left.

“Maybe I should take it out,” I said to Thoby.

“Ok, get it out,” he said, looking at her gasping for air.

I stepped off the bus so I could have room to open my bag and grab the EpiPen. I also didn’t want everyone to see my camera equipment. Then the fat Dominican woman began yelling at me to get back on the bus and let’s go. I told her to shut up. I couldn’t believe her. I reached into my bag and pulled out my EpiPen and stepped onto the bus. I handed it to Thoby.

“How do you use it?” he asked.

I pulled out the instructions and told him how to do it. She was still breathing heavy and it looked like she might pass out. The air in the bus was warm and stuffy.

“Do you want me to do it?” I asked.

“Yeah, you better do it.”

I took the EpiPen out of its plastic holder. I had to stick the device into her thigh and press a button that triggers the needle.

“Are you sure she wants it? I’ll do it, but I want to be sure she wants me to do it,” I said.

He was talking to calm her down and breathe normal.

“Do you want me to do it?” I asked.

“I don’t know. Hold on. Let her breathe a little more,” Thoby said.

We all watched her as she seemed to begin breathing better.

After a while he said, “She doesn’t want it anymore.”

“Ok, I’ll just hold onto it just in case she needs it.”

As we pulled back onto the road I told Thoby about what had happened since he had dozed off.

“I thought we were going to die. I was bracing myself for a horrible crash,” I said.

All I wanted now was to get to the airport alive. The driver continued to drive just as fast as he had before. He was driving across the stripe into the middle of the road. A truck came at us and he swerved out of the way as the bus bounced up and down across some potholes. Everyone screamed again. I did, too. The Haitian woman began breathing heavy again. This driver is nuts, I thought. I was not the only one. Because of the seating arrangement, Thoby and the man sitting next to the driver were facing me. They kept turning their heads to see the road ahead. A few minutes later Thoby dozed off again. I forced myself to stay wide awake. The driver had his window partly opened, but I was worried he might fall asleep, never mind crash for real. It was like torture watching the driver. It was dark everywhere. He insisted on driving fast, and kept going in the middle of the road. Perhaps he was in the secret service, too. He chatted with the man sitting next to him, who smiled as he talked to the tall Haitian girl who had cried earlier. It appeared he was hitting on her but she didn’t accept his advances. Good for you, I thought.

I guess it was survival instinct, but I managed to stay awake. The back of the folded seat where I sat only went halfway up my back. So I had my weight pressing against its top bar the entire ride. The middle of my spine was killing me, and would be sore for months.

After what seemed like an eternity, we reached the capital. We stopped on a main street off the highway and a family of Haitians and some others got off. The owner of the hotel either was full or did not want them there. The driver stopped at another place around the corner. A one-legged Dominican man begged us for money. I told him I couldn’t help him. We made another stop like this one. The streets were empty. It was around 3:30 a.m.

Back on the highway, I demanded they take us to the airport. I spoke for the rest of the Haitians who did not speak Spanish. The man sitting next to the driver said they would take us there for $20 per person. That’s when all the bad Spanish words I knew began flowing off my tongue. I directed most of these words to the fat Dominican woman. I said that we deserved our money back, and that they should be paying us for almost killing us while taking over 20 hours to get here because they were greedy. The Haitians couldn’t understand me but they knew I was upset. The one from Miami wanted to pay the $20. I told him that we’re not paying. It’s a matter of principle. Thoby had no money; he used his last cash on the $35 bus ticket and drinks he bought me. The secret service man sitting next to the driver looked confused. He turned to the driver and said, “The American doesn’t want to pay.”

The driver said that if we didn’t pay, he would drive straight to Santiago, and not go to the airport. I refused. The Haitian from Miami was upset. I kept my ground. They lowered it to $10. The other passengers gave him $10 even though I told them to hold their money because we deserved a free ride. At last I gave him $10 for Thoby and me because I didn’t want the other Haitians to be shut out. If they were not on the bus I probably would have gotten off and waited until morning to catch a cab. I kept swearing at the fat lady, saying she was the devil’s wife. I said this because I know Dominicans are very religious. I said some other bad things, too. It was around 4:30 a.m. when we arrived at Las Americas International Airport. I was dirty, sore, and tired, but it felt like a miracle to be at that airport … alive.