Sir Alexander Fleming, who is known as “father of antibiotics”, once warned that the inappropriate use of penicillin could lead to the selection of resistant ‘‘mutant forms’’ of Staphylococcus aureus. After that, everything happened like his speech; within 1 year of the wide spread use of this drug a significant number of strains of this bacterium had become resistant to penicillin. Nowadays, antibiotic resistance has become a major global health care problem and a complex challenge of new antibiotic development in the future.

Spreading resistance :

As stated earlier, the first cases of antimicrobial resistance which was caused by S. aureus, occurred in the late 1930s and in the 1940s, soon after the introduction of the first antibiotic classes, sulfonamides and penicillin. Later, the list of bacteria developing resistance is impressive, from sulfonamide and penicillin-resistant Staphyloccocus aureus in the 1930s and 1940s to penicillin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae (PPNG), and ß-lactamase-producing Haemophilus influenzae in the 1970s, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and the resurgence of multi-drug resistant (MDR) Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the late 1970s and 1980s, and several resistant strains of common enteric and non-enteric gram-negative bacteria such as Shigella sp., Salmonella sp., Vibrio cholerae, E.coli , Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumanii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, some of these associated with the use of antimicrobials in animals grown for human food consumption in the 1980s and 1990s. Recently, scientists identified bacteria able to shrug off the drug of last resort - colistin - in patients and livestock in China. Besides, in America, scientists freshly published a troubling finding: E. coli carrying a gene conferring resistance to the antibiotic colistin in the urine of a Pennsylvania woman. Not only that, there are six babies at an intensive care neoatal unit have been infected with the potentially deadly MRSA superbug in Cambridge, UK.

.

‘‘Selective Pressure’’ :

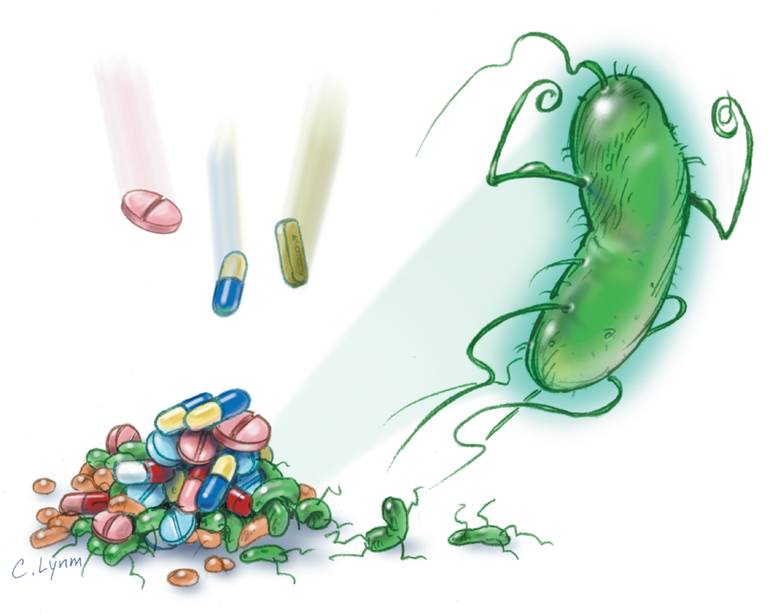

The use of antibiotics in humans results in ‘‘selective pressure’’ in the host receiving the antibiotic. The broader the spectrum of activity, the higher chances for bacteria to develop resistance. Third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and more recently azithromycin have been linked to these problems. The net result is that after the administration of the antibiotic, most susceptible bacteria in the host , the majority of which are part of the normal saprophytic bacteria colonizing that individual, are eliminated thus selecting only those resistant bacteria capable of surviving despite the presence of the antibiotic.

Antibiotic investment :

In most pharmaceutical companies that have a Division of Infectious Diseases, the budget for anti-infectives is limited (as is the budget for other therapeutic groups), and in recent years a significant amount of the anti-infective investments made in the industry have been directed to new antiretroviral agents at the expense of antibiotics. To be more precise, from 1998 to 2003 only nine antibacterials was approved in the U.S. by FDA, which was the same as the number of new anti-HIV drugs and of these only two (Daptomycin and Linezolid) had truly novel mechanisms of action.

A promising antibiotic :

In 2015, scientists report that the antibiotic, which they have named teixobactin, was active against the deadly bacterium MRSA in mice, and a host of other pathogens in cell cultures. Unusually for an antibiotic, teixobactin is thought to attack microbes by binding to fatty lipids that make up the bacterial cell wall, and it is difficult for a bacterium to alter such fundamental building blocks of the cell. By comparison, most antibiotics target proteins and it can be relatively easy for a microbe to become resistant to those drugs by accumulating mutations that alter the target protein’s shape. In summary, the post-antibiotic era is far from over. Investment in newer anti-infective platforms is essential and urgent as it is a seamless collaboration among industry, academia and government that results in a revolution in our understanding of bacterial resistance and new approaches to control it. However, the era where acute or chronic bacterial infections used to be treated with ‘‘antibiotics-only’’ appears to have come to an abrupt end.